At Collecteurs we believe that the blockchain can become a tool to promote a more transparent, equal, and just art world. We turned to one of the experts on the issue and opened up our inbox to receive comments from our members. Our very own Eser Çoban compiled a list of your questions to be answered in a 45 minute interview.

Eser Çoban: Today we're very happy to have Wassim Z. Alsindi with us doing an exclusive AMA on all things blockchain and art. Wassim is the host and creative director of 0xSalon, a collective, which critically interrogates digital culture through discourse, events, and residencies producing lore, theory, games, and visual art. Wassim holds an editorial column, at the MIT Computational Law Report, and co-founded MIT's Cryptoeconomic Systems Journal and Conference series. His work specializes in conceptual design and philosophy of peer-to-peer systems on which he writes, speaks and consults. You can also check out his course through Collecteurs linked in his mentor profile. I will now be asking your questions to Wassim. Welcome Wassim to this AMA recording!

Wassim Z. Alsindi: Hi everybody, and great to be here. I'm really curious to see what questions you sent in and I'll do my best to try and help give some answers to those.

Eser: Awesome. It's always lovely to talk to you, so I'll jump right in with a very simple question: What is blockchain and why is it important for the art world?

Wassim: As with so many things, there's a million different ways we can answer this question, which is probably why the people listening to this have heard a million different kinds of explanations. The way I like to think about it is like a data structure. It's something like a spreadsheet or a database. It's like a new form or a new architecture for storing data. The way it's structured, is that it's like a linear append-only1 sequence, like a chain of sausages. Each one of those is linked to another one in a precise sequence, and inside those little bits that link together: we call them blocks. These are essentially batches of activities that happen on a network or among a collective or community.

So what we're doing with the blockchain is we're using cryptography to link these things together in a precise order and a precise sequence, from which we can then build a ledger.2 So really, it's just a new way to make a ledger.

My analogy, which I turn to every time, including in the course we did last year is a little accounting book. You have your ledger in your little shop in a little town before the internet. And every day you buy things and you sell things and you write those down in the book, and then you turn the page over the next day and you do it all over again. So each of those pages is a block and in the book, it's secured by rings of metal to tell you the order of things. In the blockchain, we use cryptography which is an application of math with computer science to be sure of the correct order. It’s just a record keeping mechanism - a way to keep track of who has what, who owes what, who owns what, and who sent what and where.

So why is this important for the art world? Well, there's a few different ways you can go with this idea. At the very basis we have this data structure, one of the biggest features of it is that it's censorship-resistant and it's tamper-evident, so it is hard for people to mess with it. If people do mess with it, it’s usually quite apparent. This can be useful if you think about the kind of record keeping that is important in the art world, things like chains of provenance of the ownership of artworks, or the conditions in which artworks are kept subject to a contract, as it's being borrowed for an exhibition. Or, it could be used to verify the authenticity of something. This bulletproof accounting system is a way to do that for very high value items or items where these matters are very important.

There’s also another dimension to it, which is tokens. We know that we can use blockchains like Bitcoin or Ethereum and that people can make these networks have their own tokens, their own economic systems, and people can also make their own tokens. That's one of the things we've seen arising recently such as ERC-7213 or the NFT-mania for the last few years. Those tokens are being created using the architecture and the networks of these blockchains. So there's loads of different ways we can address these questions. So I think the tokens are not the most interesting thing for the art world, but rather having a new medium that can spur all sorts of innovation.

Eser: I think you already answered what makes art on the blockchain special, because it is a new medium. So I will go on to ask: How can artists benefit from Blockchain technology?

Wassim: There's a few different ways. First, we need to accept that we live in a capitalist society. We live under a regime of capitalism. We have a creator crisis where many of us live under precarity: we don’t have permanent jobs, permanent contracts, institutions are crumbling and can’t support us. The creator economy is in crisis and we've known this for a long time. First the internet changed the rules of the game then the pandemic kind of froze a lot of parts of that. They say the art market and art world has been in ice for a few years and so people were looking for new ways to connect, to do stuff, and to create value in the process to make a living. So enter blockchains, NFTs in 2020. They've been around for a while longer, but they found relevance in the early days of the pandemic.

People saw a new way to connect with their collectors, their audiences, their fans. That for me is the most important thing that there's a kind of liberatory potential there for these technologies to help artists out. If I put on my bleeding heart socialist hat, I would hope that at the very least blockchains and tokens, NFTs and all the rest of it would at least provide a mechanism for underserved and downtrodden creators, to be able to find a way.

Eser: When we last spoke, the blockchain world was quite new and the hype was so much bigger. Now the public opinion on blockchain has changed quite a lot. Some institutions have started collecting NFTs while some are still staying out of it, and the market has slowed down drastically. So has your opinion on blockchain changed at all?

Wassim: I mean, it's funny you should ask that because my opinion was actually quite negative when the market was doing really well, when everyone was really positive about these things. I was saying the opposite things,

I think I'm just out of phase with everything, but I would say that these things go in cycles. The markets go in cycles just as art and cultural hype goes in cycles. I was just having this conversation with a friend earlier, we were talking about the kind of music that I liked, I used to make, and I used to kind of organize events, it's very unfashionable at the moment, and my friend was saying, it's coming back - you just have to wait. So you have these peaks and troughs of sentiment or hype. We are in a trough now, the market is down, a lot of NFTs have lost 90%, 95%, 80% of their value from their peak. The amounts being transacted are much lower. But I still see the green shoots of spring, as you might see if you look out your window, if you are in the northern hemisphere now and you are feeling lucky.

So I still see very interesting new projects coming out. And the more interesting conceptual projects are doing quite well both financially and in terms of the kudos that they garner. Maybe let's say more commercially oriented projects are falling a bit flat. I'm okay with that. I'm okay with the more interesting projects that are a bit smaller in scale financially doing well and showing the way or the possibilities or the potential of the medium and the more blue chip, glossy, shiny stuff falling a bit flat. That's actually music to my ears. I'm not saying that I think NFTs are the best thing ever or like some kind of revolutionary moment in media art or whatever else. But they'll definitely have a place. NFTs are here to stay. There's no putting that genie back in the bottle.

Eser: So many people at institutions have invested in blockchain and crypto. Do you think it's too big to fail?

Wassim: Well, we create our own realities, right? So if enough people believe in a thing, it's gonna succeed in some way. It might not succeed in the way that they think - as in everyone makes loads of money, but it may succeed in legitimacy and worthiness with a place in history. I think that using applied cryptography to secure value, which is the most general proposition of blockchains, is going to continue for sure. This is a trend that has been continuing for decades. And as our world becomes more digitized, more algorithmic, more computerized these things will continue to happen.

However, there are many, what we call failure modes in these technologies. So there's an economic set of failure modes where if not enough people use these things, they can't secure themselves and keep going. There's political failure modes where you might get something like a civil war inside these networks, and then that's obviously terrible news. There are also technical failure modes, for example, the cryptography of applied math that we used to secure these things is not actually bulletproof: it depends on us. It depends on other people not having computers that are fast enough to crack the code. So people are worried about quantum computing. It’s going to be a while before those technologies arrive but this does exist as a vulnerability. Nothing about this is too big to fail - it is something resilient but also fragile.

Ultimately, I think the spirit and the movement is here to stay. I just don't know which of the players is going to stay. Is Ethereum going to be here in 10 years time? Either way, peer-to-peer technologies to bypass institutions, governments, banks, and art institutions are definitely here to stay.

Eser: Okay. So we're going with a few more simple questions. What are blockchain wallets and why do we need them?

Wassim: Yeah, this is a really good question. It's really important to get right. I think it's one of those things that we live in a world where technology kind of gives us interfaces and it abstracts away the mechanisms of how things work. You log onto your online banking app and you click some buttons and you transfer some money, you buy something with a credit card, there's a whole bunch of stuff that's happening in the background but you don't see that. You just go tap your card, you get on the tram, you've paid, actually it takes a week, two weeks, a month for those transactions to actually settle. A crypto wallet is a key to a digital locker where your tokens live. And it's not like a wallet that's in your pocket, it's not a physical location.

Blockchain networks are built on a thing called public key cryptography. It's a particular kind of technical infrastructure, which means we have things called “public keys,” which are like usernames or your postal address that everyone can know, and there are “private keys,” which are your password. The wallet has the address at the public key and the password, which is the private key. That's where you locate your value and store your stuff. If somebody else has your password, you are going to have a bad time.

This is one of the security considerations around these networks. You have to keep your passwords safe. I’m pretty sure that far more value has been lost by people not remembering their passwords or how to access their stuff than has ever been stolen by thieves breaking into your house at night. So the wallet is a convenient abstraction, which makes it a bit easier to remember and handle all of these things. Machines can read strings of numbers and letters as keys - but not humans so we have things like mnemonics or pictorial representations to try to make it easier. Technology is actually not that human friendly and making it so is a big struggle. Wallets also allow your real identity to be separate from a wallet’s identity so I could have 10 wallets and people wouldn’t know that it’s me using all of those different wallets. I might have one wallet for when I interact with my local bank and my mother, I might have another wallet which I use on the darknet and I would keep them separate cause they're separate graphs of my life that I don't want the bank to know about what I buy on the dark market, for example. You can separate your digital identities from your real identity, you can link some of them or you can leave some of them anonymous. And so that's kind of why it's an interesting and useful model.

Eser: This is kind of off topic, but I've seen wallets used as evidence at divorce courts and things like that. People track actual assets through that.

Wassim: Yeah, there's a field of blockchain forensics where people are doing this detective hunt on the block. Because you have to remember these ledgers are open. Anyone can download a copy of the blockchain of a public network like Bitcoin, Ethereum, go through all of the history and try to identify who does what. These are open networks, they're not very private places. That's a good thing to remember.

Eser: So how do I convert cryptocurrency to USD or other currencies and vice versa. How does that work?

Wassim: Again, it depends where you are and how you want to do it. I could say that there are white market ways of doing it. So if you lived in a place like the USA, you could use a website like Coinbase. You send them USD and then you can buy Bitcoin on their platform and then withdraw it from their platform. Don't leave it there.

When you leave it on the exchange or on trading websites, they hold it, and that's not the point. The point is for you to hold them. I know that's more responsibility and more stressful and more things can go wrong but those websites are run by companies and companies come and go. You probably heard about this big FTX exchange collapse and like a lot of people thought it was really solid and reliable. They were friends with people in the US government, they're naming arenas in Miami, and then - it was gone. So it's very important for you to hold your own stuff.

But that’s the white market way, the black market way is to meet someone online or offline, like an affinity circle, a peer-to-peer transaction and do it directly if you want to be kind of a bit more discreet about it.

Eser: What are gas fees and how do they affect artists? Are there platforms with no gas fees and or transaction fees?

Wassim: In the language of Ethereum, which has been adopted across web3, across all these other platforms like Tezos, Cardano, Solano, and all the rest, gas is taken to refer to as computation. You can think of these networks as distributed computers. We used to call Ethereum the world computer. I would actually say it's more like a world calculator. It's not a very sophisticated computer, but it's distributed across various nodes. Gas is like the transaction fee in Bitcoin. The gas fee is paying the nodes that run the network that do the computation to do your operation. So it could be you're transacting Ethereum or a token from one place to another. You could be doing what's called a contract called minting a token or some other kind of function in an application, a dAPP or a web3 tool.

So if the blockchain is these discrete units of transactions in a linear sequence in Ethereum, the amount of gas in each block or amount of computation that this world computer can do in each unit of time is a limited quantity. That creates a bidding war to get into the blocks. Gas fees are paid so that the miners will include your block and for your transaction to be confirmed.

There is an interesting situation now where, because the miners can see what the users want to do, sometimes the miners put their own transactions in the blocks that look like your transaction, but they do it for themselves because they can see you are gonna make money. So that's called miner or maximal extractable value. This is a market within a market that happens in Ethereum and other places.

The last part of your question was about gasless transactions. There is something in Ethereum and probably on other networks where they're trying to do an abstraction, to create a way where you don't pay the gas but somebody else pays the gas or the gas gets paid by a contract. There are ways of doing that, but it's an abstraction because ultimately there is most likely a transaction that goes to a miner. The piper needs to be paid, otherwise the transaction doesn't confirm. There are other things which are more complicated, which we call layer-two solutions, which are kind of batching things off the chain and then writing them onto the chain later. A bit like a bar tab, as if you're at the bar with your friends, and at the end of the night you get the bill and you pay all at once. That saves on transaction fees because you're doing less transactions. There isn't really such a thing as a gasless transaction because there's never a free lunch in these networks. There's rarely a corporate entity that is making enough money from selling your data or whatever to let you do stuff for free.

Eser: We built CollecteursX on Algorand, which currently has a 0.001 gas fee.

Wassim: So think of a highway going through the countryside and there's a brand new highway, it just got built. We open it - eight lanes each way - and then all of a sudden it's full. You need to build the infrastructure to generate interest. After that, the demand comes and then the market starts. What you're saying about Algorand sounds to me like the market hasn't started yet. It's a bit like they're letting everyone into the nightclub for free because it's before 10:00 PM.

Eser: What are some good examples of utilizing medium specific affordance?4

Wassim: Let's talk about what these are. I made some notes because I wanted to make sure that we don't forget too many things. These are decentralized networks and they're kind of social or socio-technical systems. For now, it's still humans running these things and doing the transactions and talking to each other, there are some bots.

One of the things that I like is that we have an economic design space. We're making art out the same things we make cryptocurrencies out of, which are kind of like monies or commodities. So we can make projects that have these interesting dynamics, economic ones, for example, or like ones that have a kind of a shared decision making component.

So you can see interesting or novel ways of steering the development of a project or an artwork or making decisions in it. You can make economic games that wouldn't be possible elsewhere. We can use all of these weird cryptographic tools and tricks. We can do things like render the artworks completely inside these networks so we can make extreme native artworks, for example. There are all of these little interesting corner cases, edge cases of interesting things we can do.

There's an artist called Sarah Friend who had a couple of interesting projects over the last few years including one called Off (2022). This was a series of black squares and rectangles in the dimensions of various screens, phones and computer screens. That's all well and good, like Malevich in 2022. But what was really great about this was each of the 256 tokens in the collection also came with a fragment of a key. And this key would then unlock a new artwork, a secret artwork, and you needed two thirds of the owners of the key of the fragments of these keys, two thirds of the owners of the NFT to collaborate, to have enough of the key to open the lock. And so all of a sudden you're turning this atomized world of art collecting into something that's a kind of collective game. I really like things that invert existing logics.

Installation view. Sarah Friend / Off: Endgame, 2022. Photo: Frankie Tyka.

Another project that Sarah worked on was called Life Forms (2021), and that one was quite simple. Anyone can make a token, it's free. You just have to pay the gas fees. But if you don't send it to someone within 120 days, it dies. And so you can't keep it, you can't hoard it. It's not about speculating and hoarding it, so I like that. And it also gives you this sense of contingency, ephemerality, like the fragility of life, to these very unliving technical substrates.

I really enjoy these networks, and this is some of my more philosophical practice. We look at the kinds of temporalities, the kinds of time regimes that these networks create, because they're divorced from the calendar and the clock that we've known until now. People are working on ways of conveying and representing and experimenting with these new temporalities on the blockchain. There's a project called Nascent, which is doing some very interesting work. It is taking data from the networks. So the blocks that they come as they're discovered in these networks, they might not come at equal times, for example, or they have random information in them. There's some things which we can't predict;Number of transactions, the amount of gas that's being used, the timestamp of the transaction. And so they're making art that evolves based on the latest state of the network. So these works are alive. And if you combine this idea of the contingency and this evolution with the fact that you're rendering or you're creating all of the work inside the network, I think that's super interesting for me.

You've kind of created your own universe. Everything happens inside this virtual environment. And so I'll leave it there, but there's a few other examples we can go down, but I just give you like a flavor of the kinds of places that people are going these days.

Installation view. Sarah Friend / Lifeform, 2021. Photo: Hannah Rumstedt

Eser: Sarah Friend's work actually reminded me of this email that we received from Roberto Toscano, one of the collectors on the platform.

He says, “I've been thinking about reaching out to a few artists who have done important video work that are more or less unreleased, I think mainly of Matthew Barney and his gigantic River of Fundament (2014), though we can think of many other examples, the point being the artist and the collectors who helped fund the pieces should welcome these works being made into limited editions, which they would hold the keys for and if you bought the piece in the past, you get a private key controlling the ownership of the piece while allowing the works to be distributed widely and for free. What do you think of a model that allows collectors to be the patrons of the artist's work, as well as holding a key to the ownership?” There are fractional ownership models now, which turn artworks into securities and therefore need to be regulated by the SEC in the US. Do you think fractional ownership models could be a future for the art market, or do they take away from the artwork's artistic value?

Still image: Matthew Barney / River of Fundament, 2014. Courtesy of Hugo Glendinning/International Film Circuit

Wassim: Yeah, I think this is actually a great, great question. Great point of discussion. So yes, sir, thank you for that one. I like the idea that you can have a way of signifying, or making real or explicit contributions that people could make to the work.

You are giving, but you are keeping it open so people can participate, people will access the thing, but then there's also a way - through a badge or roset - that says, yeah, I helped with this, I contributed to this, and that token then also could have value or not. That would mean that was a way of funding the public release of work. I think it's a really nice idea because you are returning the work to the community - I think it's really nice.

The art world is also a legal world, right? So it might be that a lot of these works are being prevented from being released because of something legal. I run a law journal by the way, at the MIT Media Lab, one thing I've noticed is that money makes law problems get smaller or go away. If there's money, you might be able to solve some of these problems and get this thing out. So I actually think it's a great idea and what I would say is, take a look around, see if people are already trying to do this.

There might be people working on this. I know there's a bit of work on fractionalization of NFTs, there's a platform called Spector, for example, that's doing that. But there is, as you say in this comment, the regulatory question there. So the thing about NFTs is they're non-fungible. So one is never the same as the other. And one of Aristotle's definitions of money is that things should be fungible. Securities should also be fungible, according to the Howey test, according to the Securities and Exchange Commission in the US. And so if you make these non fungible tokens, fractionalize them, you're kind of making them more fungible again, and then they start to look more like securities than they did before.

There is no hard and fast line, especially with these technical objects. They're kind of hybrids of all these different things. But what's happening right now in the US which sets the tone for the whole world in terms of regulation of these things, is they're being very harsh. There's tough talking and there's lots of action. They don't want people to think that they can just make securities and it's not a problem. I actually used to work with the current head of the SEC at the MIT Media Lab, and I thought he was quite nice, but he seems pretty, pretty mean at the moment.

So that was a surprise to me, but the last part is about the future of fractional models. So if the regulatory problem can be overcome, this is quite a healthy mechanism and effect, like to increase fairness and to widen distribution, widen ownership. I don't know if they take away from the work's artistic value because it's up for debate still these days, after hundreds of years where value comes from. If nobody appreciates the work, less people will value it. I mean, I don't know anything about art. I just like to see everything out in the public domain. I'm like a hacker so I'd like to see these things, the beast to get freed. So yeah, I think this is a great idea and a great question. So thanks for sending it in.

Eser: So what is the potential of blockchain for existing art collections? Can blockchain technology contribute to the enforcement of more transparent and secure transactions that is convenient for both collectors and artists? And can they be applied to physical works or for more ephemeral works like performance or relational aesthetics?

Wassim: There's lots of different ways we can go here and I'd say that there's potential to use blockchain for existing works and collections in different ways. There's a way that we can use these things to create records. We can index and archive characteristics, properties of our collections. We can use tokens to represent rights to access control, ownership to physical objects, for example, location or space.

Now for something ephemeral. I mean, the tokens kind of live forever in a way on the blockchain, but that doesn't mean that they can't represent a moment in time or an event. So imagine it's a conference or a festival. A biennale has to use a room for performance. But then, after that, the token doesn't have a use anymore. It's more like Memento. It's more like your brochure or your silk scarf. They can be used in an ephemeral sense, and the token could then exist as a kind of a festival wristband.

It's like your digital festival wristband that lives in the blockchain for all eternity. And that might actually be worth money. I don't know, who knows, if these things become collectible or kind of like rare objects in their own right in the future.

Eser: How does the secondary market work with blockchain? What are the benefits?

Wassim: So again, you've got a white market and a black market with all of this blockchain stuff because nobody can stop people from doing things. And there's different jurisdictions which are less tightly regulated than others.

So let's go through a thought experiment: an artist creates an edition or a project. And then those might go onto a platform like OpenSea, Folio, or Feral File. Or it might be something that they issue themselves directly. I have friends that are building their own exchanges now, to release their editions. And so once it's left the artist's hands, it's in the market. After that, it depends on which venues people are using, but, secondary markets are driven more by speculation than fundamentals. So it can be that prices get a bit disconnected from reality on certain platforms or in certain jurisdictions. And I think one of the most important conversations that's going on these days is around royalties. So we have this way of encoding a logic of creative royalties into the smart contracts that issue the tokens that NFT projects emerge from.

So imagine speculator 1 buys the token for 10 Ethereum, and then a week later they'd sell it to speculator 2 for 50 Ethereum. So some people are building in this idea of a recurring royalty - for instance, the artist would get 5%, 10%, 2.5%, 1%, as a function each time the transaction happens through the market.

Some marketplaces support this facility and some don't. There's a big conversation now about whether there should be some kind of action or ethical consideration around whether a platform or whether a group of people respect the royalties of the artist as encoded into the logics of the project. That comes down to where you sit on the political spectrum: do you think in terms of collective fairness, or do you think in terms of individual freedom? That is very much a personal choice. We'll just say in the crypto space, we have quite a lot of people that lean a little bit to the right.

The individual freedom thing is quite strong in crypto, less so in the web3 world than in Bitcoin, but still in a little bit of both. So the secondary market, I think it works a bit like it does in the traditional art world. You've got quite legit things and you've got slightly less legit things. It's complicated and there's a lot of moving parts. I think a lot of the things that we see in the crypto art world, particularly in the market industry side of it, are reproductions or new iterations of the existing machinery and logics and mechanics of the existing artworld.

Eser: So how can collectors support artists through blockchain?

Wassim: Lots of ways. You have all the ways you could do it before, whether that's working very closely through patronage, and then that could be rewarded or acknowledged with things like tokens. There's an interesting zone opening up now, which we call the phygital zone. It's a combination of the words physical and digital. So the idea that these two things are meeting together in the metaverse. People talk about the meta versus a phygital space or something like that.

I wonder if there's new horizons for objects, experiences, happenings, and events that straddle the real and the virtual. I think that is probably a new horizon for new kinds of ways to interact with the artists or new kinds of ways to support them. We still have all the ways we had before and now we have some new ones. If you buy a token, buy it from the artist and pay the royalty. Like actually that's the way you do it. Pay the royalty to the artist. That's how you support them. Full stop.

Eser: So I think this kind of relates to the phygital thing as well. There's a big debate in the NFT world about utilities. So like a project having some kind of utility. Do you think that an art project on blockchain needs some kind of utility to actually be successful? Should it offer something physical or something else on the side?

Wassim: I really don't think there's a rule. Just like in the real, legacy art world, there's no rule. For example, you can't just make a formula for success and follow that and it works every time. So I think it's always individual, on a case by case basis.

I see some big projects like Crypto Punks. One of the reasons that it took off ostensibly is that the owners of the tokens were given rights to commercially exploit their tokens. For example, you could make a TV show about Bored Apes. Not Crypto Punks, I'm very sorry, Bored Apes. So Yuga Labs, which made the Bored Apes platform, gave the owners of the NFTs in that collection commercial rights to exploit the likeness of their NFT in whatever way they wanted, within reason. So you had the situation where there were famous people making TV shows with their Bored Ape. Seth Green owned one of these Bored Apes, and he was making a TV show with it. I'm not going to make any moral judgments about this.

What happens between a man and his Bored Ape is between him and God alone. But he lost it - he lost access to his ape. I think a wallet was compromised. He lost his token and then he didn't own his token anymore and so he couldn't make his TV show because he didn't own the token with the rights. That is an example of utility bringing value, but then there's always another side to it. But a lot of successful projects haven't had explicit utility.

Images courtesy of Bored Ape Yacht Club.

Eser: Yeah, it's art for art's sake, most of them.

Wassim: That's nothing new. We've been doing that for thousands of years.

Eser: I think Eminem made a music video with his Bored Ape, but I don't know how much that brought him back to him.

Wassim: The last time I checked on that story was that the person that had hacked Seth Green had sold the token to someone else already. And then you've got the sucker that paid lots of money for his thing and it wasn't their fault. So I don't know what happened, but maybe now Seth Green can use the token even if he doesn't have it back? I don't know.

Eser: Maybe he can use the story.

Wassim: He can make a TV series about the story. Yeah.

Eser: Yeah. “All my apes are gone.”

Wassim: Or “All your apes belong to us.”

Eser: Well here's the big question. What is the current state of the environmental concerns with blockchain? Will we live to see most of the polar ice caps melt?

Wassim: I'm happy to report that since I did my "Futures of Art History" talk with Collecteurs in May of 2022, the environmental situation with Ethereum is way better.

At that point, we were looming on the cusp of a big change, what was called “the Merge,” the idea that we would switch out the proof-of-work, this energy intensive blockchain mining, that started with Bitcoin, that Ethereum also used. And it would switch to this thing called proof-of-stake, which is energy efficient. This replaced a costly real resource, the burning of energy with a cheap virtual resource, which is the rendering of liquid of the coins' stake. And so Ethereum's expenditure of energy has gone down a lot. That's great. Thank you very much to Ethereum. However, Bitcoin is continuing at pace, so it's actually using more energy than it's ever used before.

And bear in mind, it's only at the third of its maximum historical price and it's using more energy than it's ever used before. So we can now actually close the book on this conversation for everything except Bitcoin, in my opinion. There is obviously e-waste, there are kind of specialized computers being used to generate randomness in Ethereum, but those things are very small concerns compared to the colossal amount of energy that Bitcoin uses.

That's a core subject of my philosophical and artistic practice. So I'm happy to say that, we might live to see the polar ice caps melt, but it won't be Ethereum's fault. Let's put it like that. About the question, I know it came from a friend of mine in Singapore, Alfonz, and he's younger than me. He's quite a lot younger than me, so I'm gonna answer this question by saying I'm probably not gonna see it, but you might see it.

Eser: Let's hope none of us sees it.

Wassim: Yeah, I hope not. No, I have an optimism that the earth has more feedback loops than we give it credit for. Actually, I'm wearing a t-shirt of this talking Bitcoin mining machine. That's a feature in our play. In that scene, Hashi's reminding everybody that there used to be a subtropical climate at the poles. The planet was warmer before and then it got colder, and now it's getting warmer. I still think we should be worried and we shouldn't trash the place. But I'm hopeful.

Eser: So blockchain has brought along some alternative financial organizations. What exactly are DAOs and do you think they bring useful new models?

Wassim: DAOs are a legal and organizational innovation. This idea came from the early days of crypto where we were doing very basic things - just trying to send transactions, information from one place to another. This idea of DAOs as decentralized autonomous organizations are a way to build institutions on the chain. We're building whole organizational logics on the chain in this virtual space, collectively, at scale, in a decentralized way. There were early attempts to work towards this, even predating Ethereum.

The first examples of these things, in the way that we understand them today, were on Ethereum. That started in 2015 or 2016. There was a thing called The DAO on Ethereum in 2016, which was a speculative hedge fund sort of thing. The idea was that people would invest in this thing, buy the tokens of it, and then it would allocate capital on projects, and then it would return value to stakeholders. Unfortunately, the rollout of this thing was a little rushed and the code wasn't perfect, and there was a vulnerability in it, and then there was a big catastrophe. That set back the world of DAOs several years, but now it's come back in the last few years, there's been a big renaissance in using the infrastructure of web3, to build sandboxes or environments for collectives and organizations to be able to work together in a very distributed and sovereign way.

People are using DAOs to collectively organize and do all kinds of things, both inside art and outside; to determine, to steward, and govern some precious resource. It could be a bunch of funds for collecting art. It could be a bunch of NFTs. I have friends that work on new ways to make art funding distributed more fairly using things like DAOs and the models that they engender. There was a DAO raising money for Ukrainian defense, a charity DAO. You could just send money to that and they would send it on to the frontline. What I like about this idea is, you don't have to ask anyone for permission to do this. Anyone can go off and spin one of these things up. It's getting easier and easier with new kinds of tooling and infrastructure. DAOs are these new on-chain organizations that we can create. Let me just say a little bit about the term, because it's a weird word.

There's a D and an A and an O. That's a decentralized, autonomous, organization. What I will say is that a lot of the things that are called DAOs these days are not particularly decentralized, not particularly autonomous, and not particularly organized. So it's now this word that's just a very wide catchall. I think that by the time we go live with this, there'll be a video on the YouTube channel of Unsound Festival, where myself and some friends talk about DAOs and web3 stuff for a very, very long time. It's for a music crowd, which I think has a similar kind of depth and breadth of knowledge than an art crowd. So if you want a deep dive on DAOs, I would recommend going over to the Unsound Festival on Youtube.

Eser: Thank you. With music too, DAOs are very popular. A lot of people are interested in it. Let me ask two more questions because I still have a lot, but I'll ask you just the most important ones. So what is the post scarcity future? How do you see blockchain changing capitalism? And what happens to artworks when they're no longer scarce? What new criteria could create value instead of the outdated or fake scarcity model?

Wassim: This is a really nice question because now we're getting into sci-fi territory. And this is something I alluded to in my "Futures of Art History" talk on Collecteurs Academy. We still live in the societies we live in now, and the capitalism that we live under in the real world is very much one of a scarcity imaginary. There's money, there's not enough of it to go round. Everything's expensive. We have to work hard for money, we can't save or get out of that cycle. Then blockchains arrive as this architectural substrate for creating new kinds of economic and financial logics as well as everything else. And so, the anarchist in me was really hoping that we would see some radical practices, especially in terms of imagining alternatives to capitalism or extensions, their evolutions thereof. But most of what we see in the blockchain space now is kind of like, it's the evolution of capitalism, but just way more capitalism: capital C. It's like a fork in the road and it can go both ways. So I see now some of the most capitalistic activities I've ever seen in my life happening on blockchains.

There's a thing called decentralized finance, which happens on Ethereum and other places, which is a little bit connected to NFTs and DAOs. And that is the most crazy speculation you've ever seen, honestly. It's crazy. But then on the other side, I've got friends in Berlin that work on projects like circles, which is a universal basic income that they're trialing and modeling on a blockchain.

The challenge with things like that is, how do you ensure that this currency or this monetary system or this quality system retains value, has value because the supply is increasing and you're trying to say one of these things equals a euro or equals a loaf of bread or something like that.

There's always this big challenge on how you maintain confidence in these systems that aren't based on scarcity. And I don't really know if we have the answers yet. And by the way, I'll just say that the existing financial system looks like it's based on scarcity, but someone has got a printing press and they're printing money like crazy. It's just that you don't get that money, you just get inflation. That's called the Cantillon effect, where the people that are like at the pumps, pushing the money out, they're advantaged because they can act before the effects of the increase of the money supply are noticed. And by the way, the inflation crisis we're in now seems to be quite closely related to all of the Covid stimulus.

It's like more money flows into the markets and the economy, and it pushes the prices up. So in terms of post-scarcity futures, the key is, how do we engender confidence in the systems? I don't know, we haven't got an answer to that question yet, but the more of these UBI experiments we see both on the blockchain other ways, the better. There's lots of trials of UBIs in Finland, New Zealand and Ireland. So there is interest in governments to do these things because it also simplifies welfare states. All of a sudden you just give everyone stuff or a negative tax rate or something like that based on your means.

It's way simpler than the way that the benefit system works in England or Germany or the US. In terms of the last question about what happens to artworks when they're no longer scarce and all of that? Well, I mean we have this kind of tale from history, from crypto art. It's amazing that we now have a history of this thing because it's only a few years old, but in 2017 and 2018, the first big wave of NFTs on Ethereum, there were two big projects, which stayed in everyone's minds. One was Cryptokitties and one was CryptoPunks.

And the Cryptokitties were very cute and very sweet and you can breed them and it's very lovely. But they weren't scarce because you could make more, like a boy cat and a girl cat meet, and then there's a third cat all of a sudden. Whereas with the CryptoPunks, they're a bit more like incels or something they couldn't breed. So they're scarce, their supply is limited. And if you look today, CryptoPunks are worth loads of money and the Cryptokitties aren't. So there is something about scarcity and collectibility and value, especially when we are talking in a kind of a frame of collection. If we are talking in the terms of a frame of community or togetherness or utility or something else other than speculation, then you might start to see more, kind of positive points for post scarcity crypto artworks in that sense.

Excerpt from Crypto Kitties’ trailer.

I'll mention one cool, non-post-scarcity crypto art project, which is Kudzu by Hart, Denoch, Williams and Rennekamp. That was kind of an NFT virus, so you couldn't buy it. You could only get it by transacting with someone on your social graph. Once you get it, you can't get rid of it. There's no transfer function. So that's nice because the supply's actually infinite and it's propagating through a social graph, through the graph of people that you know, your network of relations, so to speak. You can't really sell it. Even if you can't transact it, you can technically sell it. You can sell the account or the wallet or something. But it's like an anti-speculative break on the ability to monetize something.

Folia by Kudzu. ∞ Edition. First NFT virus artwork, as part of the Fingerprints Collection.

Eser: I'm seeing that more often with these open editions now too, where people can just go in and start minting. I'm trying to understand how that works because there's an infinite amount and you can keep minting the same artwork, but it's going in that direction in some way.

Wassim: That's post scarcity. If there's no limit and anyone can do it, then your limitations are just cost of production, the gas fees and the minting and so on. The real question is, would these things retain value or market interest or retain the imagination of speculators?

But this is a platform of collectors, so people might have different opinions.

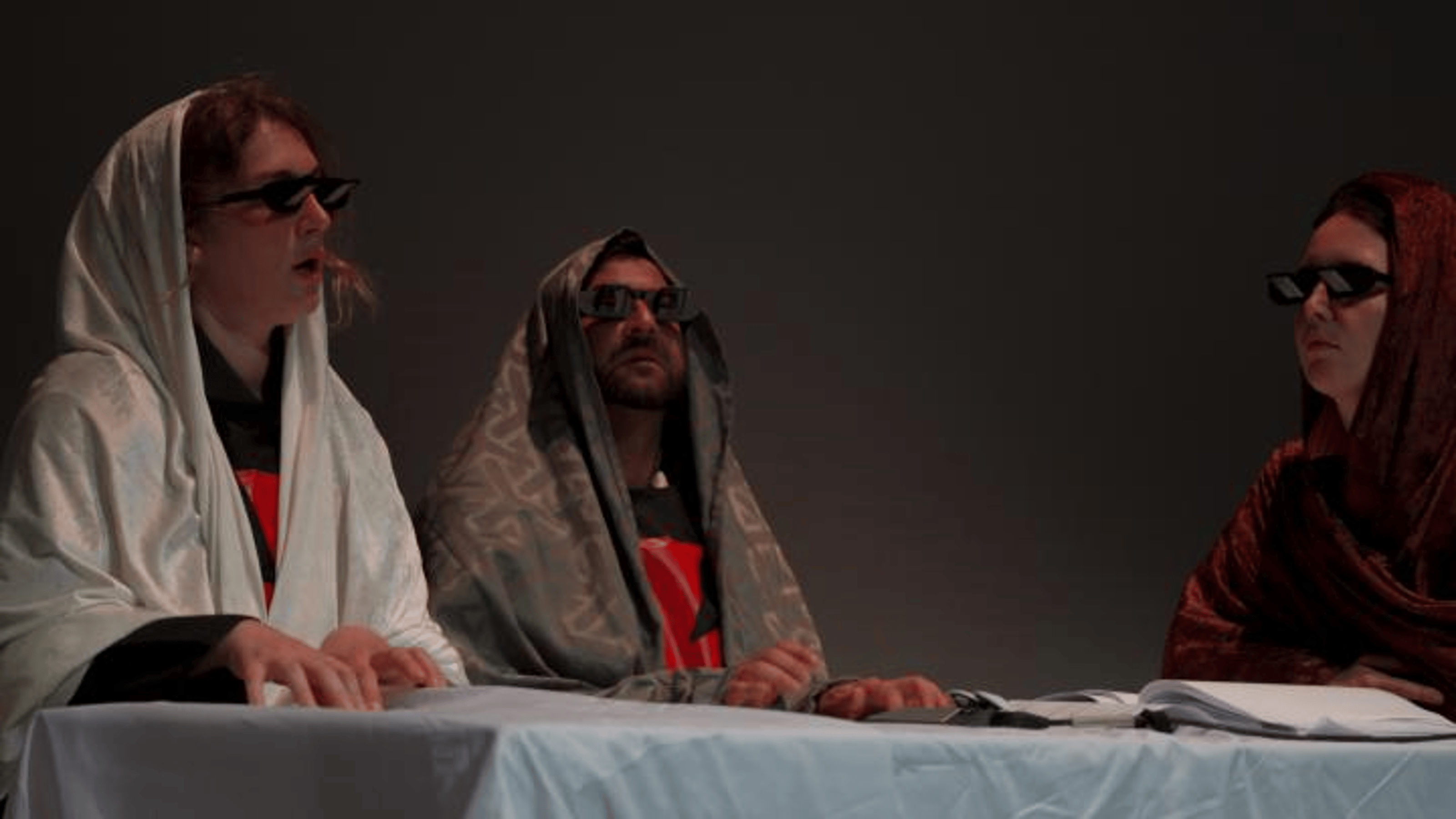

Eser: I'm going to combine two questions into one because I wanted to ask you about some of the work that you've done recently. You have recently presented a satirical play on Bitcoin titled, the Black Hole of Money (2022). Could you tell us where the idea came from and how the play took on blockchain in the future of our economies? And finally, could you tell us a little bit more about the work that you do at 0x salon, and if blockchain immersive technologies have contributed to your collaborative work?

Wassim: Thanks for giving me the opportunity to advertise my work! Last year we did this residency that the European Commission and Ars Electronica initiated called Starts, which is an interdisciplinary science, technology and arts program. They asked us to address critically the role of blockchains in society. And because I'm predominantly an expert in proof-of-work and in Bitcoin, we decided to probe the ecological and environmental tension between Bitcoin - which has no upper limit to its desire for energy and no ability to discriminate between the cleanliness of the energy sources being used to power it - and humans, us. We live on earth and Bitcoin lives on earth because of the speed of light. Bitcoin can't actually go too far away, so we're stuck here with it, and it wants all the energy and we need some. The sun gives us a finite amount of energy at the moment. So we live in a domain of scarcity, in terms of energy and Bitcoin wants all of it.

Wassim Z. Alsindi & 0x Salon / The Art of Indifference: The Black Hole of Money, 2022.

That's the bedrock of this art project we did. What we did was we built a timeline of a hundred years, the whole of this century. We tried to understand possible futures mediated by Bitcoin and how humans tried to respond to this kind of potentially existential problem. I see Bitcoin as quite religious. I see cults within it. With humans, I guess it’s a universal thing, but we created these semi religious units inside Bitcoin against Bitcoin. We really took it to a grotesque and over the top apotheosis or conclusion. There are videos documenting that on the 0xsalon website if anyone wants to take a look. I'll just say as a kind of addendum that we mercilessly based and ripped off Shakespeare for this work. I was punished poetically because they gave us a theater next door to the castle that Hamlet was set in to do our premiere.

I felt very seen by the universe that they did that. But we had a good time. It's all documented online. We'd love to find more theaters to work with to develop it further. So yeah, please get in touch if that's your thing. And in terms of the salon more generally, it's an artist-run organization and at its heart as an event series discussing various topics around digital culture and then a community formed around that. We started writing theory, art, games, law, philosophy, poetry, and so on. And a lot of it is informed either directly or indirectly by blockchains and the way that they interact with our humans. Social networks interact with these technical systems. It's very much a collaborative thing.

I would say that we haven't actually used the blockchain that much because we're critiquing it. I've got this idea of a spectrum of crypto art and there's some people at one end where they're kind of on-chain extremists where all of their work is rendered inside the chain and it's all to do with the network. If you look at Nascent and Straylight Protocol, those are great examples of those kinds of extreme on-chain works. I would say my work is extremely off-chain where I'm talking about Bitcoin and proof of work and whatever else, but we're not using it. We're really critiquing it from a distance. Blockchain is very much both a pedagogical tool and the kind of conceptual foundation of a lot of what the salon does.

Eser: Thank you so much, Wassim, I hope that everyone found interesting answers. I sure did. I really enjoyed our conversation. I guess we'll check in with you next year, and see what you feel like.

Wassim: Sounds good. Yeah. Let's see if the answers change over time. Yeah. And thank you Eser thanks to everyone at Collecteurs, and thanks everyone for listening. It was fun.