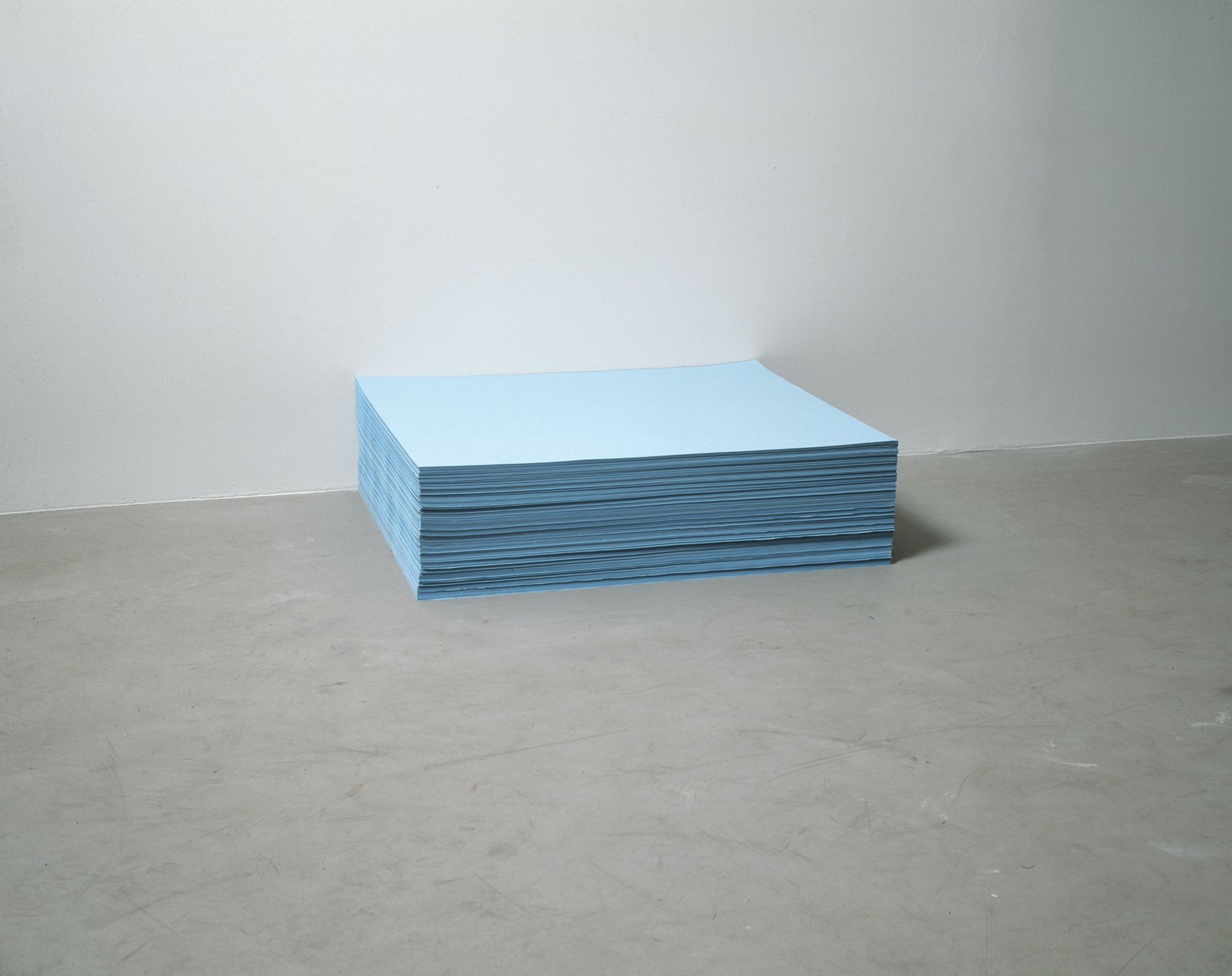

In the work of Félix González-Torres, colors, objects and numbers come back over and over again like distant memories, inevitably bound to fade, their meaning constantly reassigned. The use of blue is a striking example: it is used in most of his series, such as in the poster stacks (“Untitled” (Loverboy) and “Untitled” (Blue Mirror), 1990) and in the candy spills (“Untitled” (Blue Placebo), 1991, “Untitled” (Portrait of Marcel Brient), 1992). The color seems to hold both positive and negative connotations, with other parenthetical titles such as “water” or “fear.” A light hue of blue is often associated, both by the artist and by his contemporary critics, to memories of bodies of water and the sky, therefore to his childhood and teenage years in the Caribbean, as well as to the time spent with Ross in Canada.2 The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Family Archive includes a couple of photographs taken at the beach: in the transparent Puerto Rican water, 13 years old;3 in Cuba, some years earlier, with his mom and sister Mayda. In this second image, Félix has a handful of wet sand on top of his head. The ocean and the sky are almost the same tone of sepia, except for a much darker line, running behind the neck of Félix’s mom. This is the horizon—from Greek: the limit, the boundary. Or rather, isn’t this the place where water and sky finally meet?

González-Torres loved poetry, and Rainer Maria Rilke’s concept of “blood memory” was particularly relevant for him4. Rilke reflects on the relationship between memory and writing, and how poetry arises not directly from memory, but from a long period of distillation in which memories are forgotten, and come back as part of ourselves, as if they constituted our blood.

_For the sake of a single verse, one must see many cities, men and things, one must know the animals, one must feel how the birds fly and know the gestures with which the little flowers open in the morning. One must be able to think back to roads in unknown regions, to unexpected meetings and partings one had long seen coming; to days of childhood that are still unexplained, to parents whom one had to hurt when they brought one some joy and one did not grasp it (it was a joy for someone else); to childhood illnesses that so strangely begin with such a number of profound and grave transformations, to days in rooms withdrawn and quiet and to mornings by the sea, to the sea itself, to seas, to nights of travel that rushed along on high and flew with all the stars—and it is not yet enough if one may think of all of this. One must have memories of many nights of love, none of which was like the others, of the screams of women in labor, and of light, white, sleeping women in childbed, closing again. But one must also have been beside the dying, must have sat beside the dead in the room with the window open and the fitful noises. And still it is not yet enough to have memories. One must be able to forget them when they are many and one must have the great patience to wait until they come again. For it is not yet the memories themselves. Not till they have turned to blood within us, to glance and gesture, nameless and no longer to be distinguished from ourselves—not till then can it happen that in a most rare hour the first word of a verse arises in their midst and goes forth from them._5

Like our blood, memories do not have a specific meaning nor value whatsoever; they are just there, indiscernible. They are part of us. Water, light, blood: always new, yet the same. Their movements, their circles define our lives, while we are temporary witness to their endless journey. Nothing is lost, all is transformed, and is therefore always up for reconsideration and reinvention.

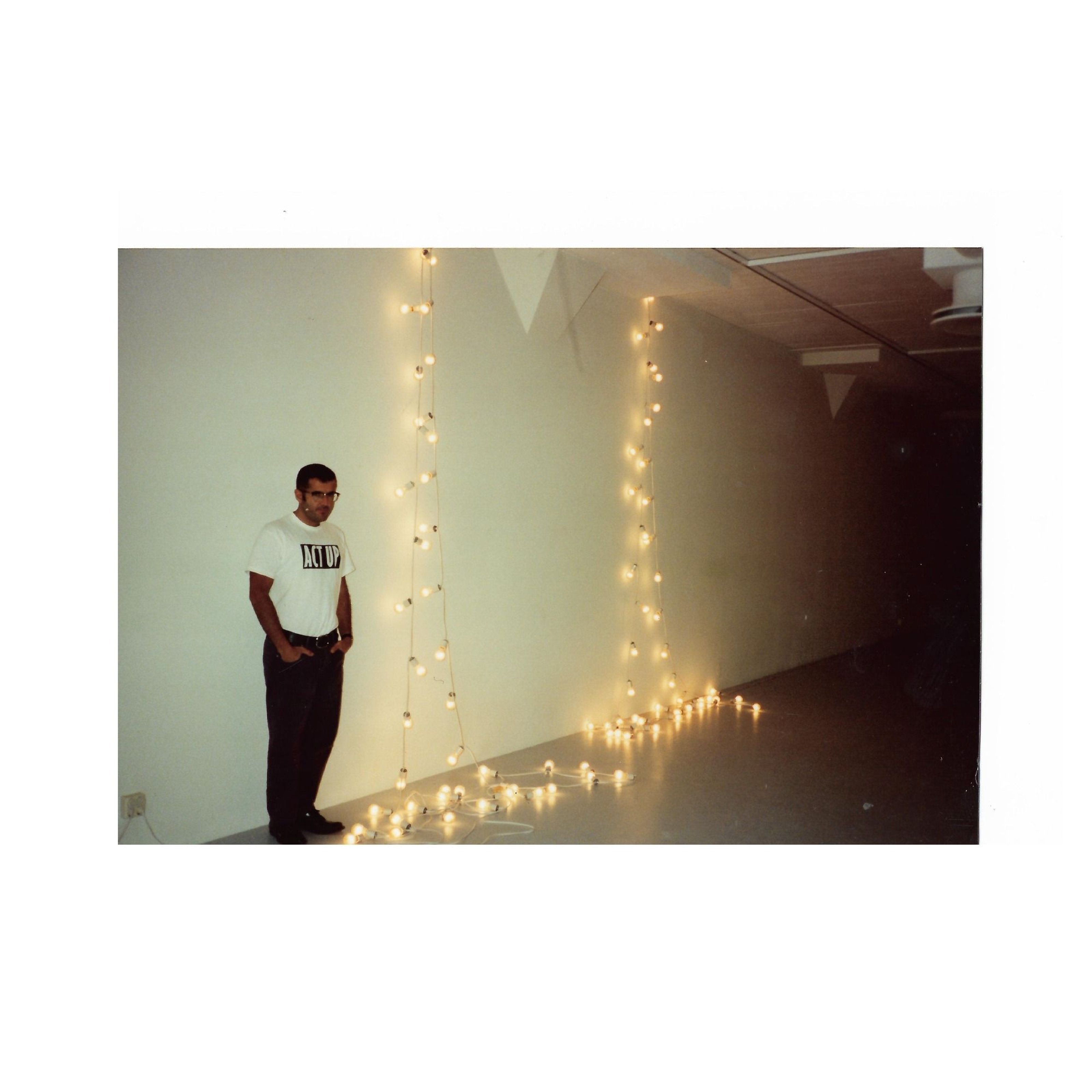

González-Torres specifically refers to the idea of blood memory when reflecting about a possible origin of his lightbulb string pieces. This all comes back to a snapshot he took of a street fair in Paris, in the summer of 1985, during his first European trip, with Ross.

The random discovery of an old photograph taken about 10 years earlier brings him back to childhood in Cuba, to a long-gone vacation in Paris, as well as to a reconsideration of a body of works which were, at the time the photo was taken, yet to come.

Following this line of thought, we encounter “Untitled” (March 5th) #2, 1991, a work in which the past and the future of González-Torres’s oeuvre eerily collide. Realized around the time of Ross’s death, and referencing his birthday, this is the first of the lightbulb string works, yet so different from the rest of them. If all the other works in this series look alike (single strings, or a series of them, with a set number of lightbulbs, for the most part 24 or 42, to be installed at the discretion of the collector, curator or installer), “Untitled” (March 5th) #2 features only two lightbulbs, and its installation is more rigidly prescribed.

It consists of two white electrical cords, approximately 140 inches in length each. On the end of each of the cords is a white porcelain light socket holding a forty-watt bulb. The two cords are meant to be knotted together about ten inches away from the top of the sockets. A nail is placed on the wall at the allotted height of 113 inches, on which the cords hang from the knot.7

The two lightbulbs, hanging this way, touch each other. The work seems to look back at several pieces in which two round forms touch in one single point, a theme González-Torres developed in works with jigsaw puzzles, mirrors8, clocks, and water pools—these last unrealized at the time of his passing.

Félix and Ross were part of a generation of homosexual men decimated by HIV, an invisible virus transmitted mainly through sexual exchange. During their lifetime, the intimate life of gay men like them was scrutinized and criminalized like never before. The idea of two surfaces touching each other, and the movement of liquids among two bodies could not at that time—as well as today, partially for different reasons—be detached by the constant fear, the threat. In this sense, it is particularly touching that the artist and his closest critics, in reflecting on the friction between the conceptual aspect of his art, which would allow for a total disappearance or alternative dissemination into the world, and his desire to be part of a gallery system (by reinventing the way it operates), often talk about a “viral presence” and “total infiltration.”

For González-Torres, it was not enough to be embraced as a Latino artist, or as a gay artist, and to be part of the cohort of diverse, identity-driven art celebrated by some forward-looking institutions, yet kept at the fringes of the critical discourse and of the market. Félix wanted to be in the middle of it all, while embracing all of his contradictions and complexities: gay and Latino, yet not necessarily loud and colorful; conceptual, yet not constipated10.

Looking back at the art historical memory of the ready-made, González-Torres’s pieces are for the most part fabricated ad hoc, while looking as simple objects, widely available. The works are all untitled, and still, parentheses guide us to possible meanings. Through these strategies, the memory of his art and of his life infiltrate our own lives in unexpected ways. One example: “Untitled” (Throat), the smallest of all of the candy pieces, is dedicated to the artist’s father, who died of throat cancer soon after Ross’s passing. It consists of few cough drops placed on his father’s handkerchief. Since I first saw this work in Frankfurt, with my friend Monica, it’s been difficult for me to melt a cough drop in my mouth, without thinking about my father. In the same way, a string of lightbulbs at a restaurant, or at a “sagra” back in Italy, might remind me of Félix and Ross’s time in Paris, or of Félix’s childhood in Cuba (although I know virtually nothing about any of this), yet at the same time of my times with some of my own lovers.

I avoided writing about myself for all this time, all these words. Used all these quotes to keep myself at bay. And here I am at last. González-Torres’s work not only seems so present, but also, the little I know about his life, and his relations, all has always felt so real. This has certainly to do with my own age, and my queerness, and my Southern European culture maybe, all aspects of myself that I feel I cannot possibly sidestep while writing about his work.

Much has been written, and said by González-Torres himself, about the simultaneous address in his works to ideas of destruction and preservation; intimacy and public realm; concepts and feelings. When it comes to how memory and the past are addressed in his works though, I feel there are no opposites at play anymore. The entry points to the work’s possible meanings are narrow enough to signal specific events, yet so wide to embrace our memories, as well. It is like one of those narrow inlets in the Caribbean, often topped by a decrepit Spanish castle, which open to enormous bays, at the end of which the most impregnable harbors prospered for a long time. Sitting on the banks and looking beyond the entrance, at the open ocean, you don’t distinguish water from sky anymore. They touch each other.

Pietro Rigolo is Assistant Curator for Modern and Contemporary Collections at the Getty Research Institute (GRI), Los Angeles. In 2011, he earned a Doctorate in Art History from Università degli Studi di Siena / Istituto Italiano di Scienze Umane. In 2013, he joined the GRI as the subject expert in the team processing the Harald Szeemann papers, and has been part of the curatorial team of the exhibition Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions, which opened at the GRI in February 2018 and traveled to four other venues internationally. He has published numerous papers and catalog essays for the Istanbul Biennale, Fondazione Nicola Trussardi, Pirelli HangarBicocca, Castello di Rivoli, among others.