Today, our guest is someone who is at the front line of countering state and police violence. He is a London-based Israeli architect who was recently banned from entering the United States. He came to prominence through detailed digital reenactments of incidents regarding human rights abuses and disputed assassinations. Eyal Weizman is the founder of the Turner Prize-nominated research collective Forensic Architecture. Forensic Architecture is known for its use of architectural, spatial, and technological analysis to uncover violence. Weizman’s work with Forensic Architecture includes an investigation into a CIA drone strike in Pakistan that was presented in the United Nations General Assembly; an analysis of the Chicago police killing of a barber that lead to an investigation by the Mayor and the Chicago Police Department; and an inquiry into the Israeli bombing of Rafah that informed the International Criminal Court’s recent decision to open an investigation into the possibility of Israeli war crimes in Palestine. Forensic Architecture had a prominent role in the resignation of Warren Kanders from the Whitney Museum board with their project Triple-Chaser, an investigation into the uses of teargas and rubber bullets manufactured by Safariland Group, owned by Kanders. Weizman’s work not only documents and informs global systemic violence, but it also is able to enact social and political change by forcing the establishment to change. Weizman’s work is truly the answer to the question we posed with SUBSTANCE 100; “what is the purpose of art in the 21st century?”

Evrim Oralkan speaks with Eyal Weizman via phone –due to the ongoing pandemic– from London:

Evrim Oralkan (EO): I’d like to start with your recent US exhibition that opened in February 2020 at the Museum of Art and Design in Miami. Before you were scheduled to fly from the UK, your wife, Inez Weizman, who traveled to the US with your two children, were stopped, separated and interrogated for two and a half hours. The day after that, you were informed that your US visa was revoked, which prevented you from being present at the exhibition. In a statement afterwards, you said:

“These works seek to demonstrate that we can invert the forensic gaze and turn it against the actors: police, military, secret services, border agencies that usually seek to monopolize information. But in employing the counter forensic gaze one is also exposed to a higher level of monitoring by the various state agencies investigated.”

I have tremendous respect for the absolutely fearless work you do with Forensic Architecture. In a way, to me, it is a testament to the power of art and its potential to emancipate the people. What is the main motivation for you and your team in continuing this recently turned dangerous work?

Eyal Weizman (EW): It is good that you started with that statement because that statement exposed us to a new kind of violence that we identify as both digital and physical violence that operates a combination of them.

Some people that are tracked in this way are much less privileged than us. They could be targeted, could be assassinated with drones. Sometimes they could simply be denied entry to places. I don’t think of myself as one of those victims. I think of myself as much more privileged than that, but we need to identify the different forms that violence is taking towards the future. The intersection of an algorithm and a border are extremely interesting for us. And this is why we have began an entire new field of investigation that is concerned precisely with that. For us, aesthetics is a matter of detection and perception. So if an algorithm identifies my movements, my health condition, the contents of my conversation, the algorithm is aestheticized to me.

The field of aesthetics is a wide field. It’s not only about judgment and interpretation. It is about the way in which material organizations; like buildings, like concrete—are broken by a bomb or by sniper fire. The way in which plants in the forest register genocide that happened in that place decades earlier. The way in which images register, sound registers, code registers. We exist in a very multi-polar, perspectival aesthetic field and we inhabit it. We’re not only reflecting upon it. We’re not only critiquing it. We swim in it. We exist in it. And we need to be able to understand the way in which aesthetic power operates today, the way in which power today has taken on an aesthetic force.

We have moved into the field of politics, like artists, creatives, critical scholars. But the field of politics has colonized aesthetics. And the minute that they have taken over aesthetics, we have them enter into our field.

We have a few tricks. We have our creativity. We have our political commitment, solidarity and motivation and we are able to inhabit the aesthetic field. Perhaps with less resources, but with much more creativity and power. And this is why we finally meet a state agent, a police watchdog; The Metropolitan Police. Now that we’ve exposed the way in which the killing of Mark Duggan has been manipulated by them, we’re able to prove our case much better than the police. The thing is that they will try to disqualify and silence us. It’s about the field of appearances that they will not allow us in. They would say: “You’re politically biased. You’re an artist. Your words do not qualify as evidence” but we need to understand that politics has entered the field of aesthetics. Politics started to operate with much more sophisticated field of detection with videos, et cetera. So welcome to our field. And here we can find a way to answer with our counter moves.

EO: Thank you. I was going to get into Mark Duggan, but before that, I want to hear your thoughts about the current situation and the brutal racial oppression we are witnessing as a society. It’s not just a US issue. This is becoming more of a global issue. We hear it in London, in Israel. It’s spreading all over the world. What are your thoughts?

EW: My thoughts are that this spark that started the protest right now in the US… but to tell you the truth, we are deep in work and in solidarity with social movements in Chile, in Hong Kong, for a year already. This is kind of like the year of revolutions. Not 2020, already 2019, has began with it. The question for us is obviously of solidarity and of empowerment— but it’s also an epistemological question; that is to say: how to take those sparks, those split-second moments.

We know with the murder of George Floyd, it’s not a split-second. But particularly in relation to police violence cases in London, on the Mark Duggan case, it was a split-second decision. In Chicago, the superintendent, it was a split-second decision. In Israel, when the Israeli police murdered a Bedouin man, realized that he was not a terrorist but still stitched up a whole story that he was a terrorist, they said it was a split- second decision. In Eastern Turkey, the Turkish police killed a Kurdish human rights lawyer, Tahir Elçi, a split-second decision. So we have those split-second decisions that are like sparks in the dark. But for each one, you need to know how to mobilize your tools not only to see into the split second, not only to go into the molecular level of time, but from those instances, these fragments of time, those dust of temporal components, the irreducible dimension of perceptual time opens up into a picture that would show you the structural forces, the slow violence, generations of settler colonial policies in Palestine, racial segregation and slavery in the U.S. How do you see deep history in a molecular level of time?

And this is a question that I think, again, art has been extremely successful in answering, because it is through the pain of an individual. Even when you look at just the history of Jesus paintings from the Middle Ages to Chris Ofili, let’s say; in each period the suffering, the pain is described as a kind of a universal, taking from a single wound up to structural conditions. I mean, that art and aesthetic sensibilities can become relevant because it is within the split second, within this unique molecular incident that is irreducible that we find the way to map out and chart the areas in which we are.

EO: Absolutely. I want to go into Mark Duggan a little bit. The investigation was recently released and it was also published on the Guardian as well. The killing of Mark Duggan at the hands of the British police, which back in the day, incited massive protests in London in 2011.

Do you think it is possible to create a collaborative model in the U S. that a similar type of investigative research is widely available for police killings and brutality in the past and in the future? I understand that the agency Forensic Architecture is not easy to operate. Obviously it’s a very detailed work, but is it possible to take this work and make it widely available to a collaborative model?

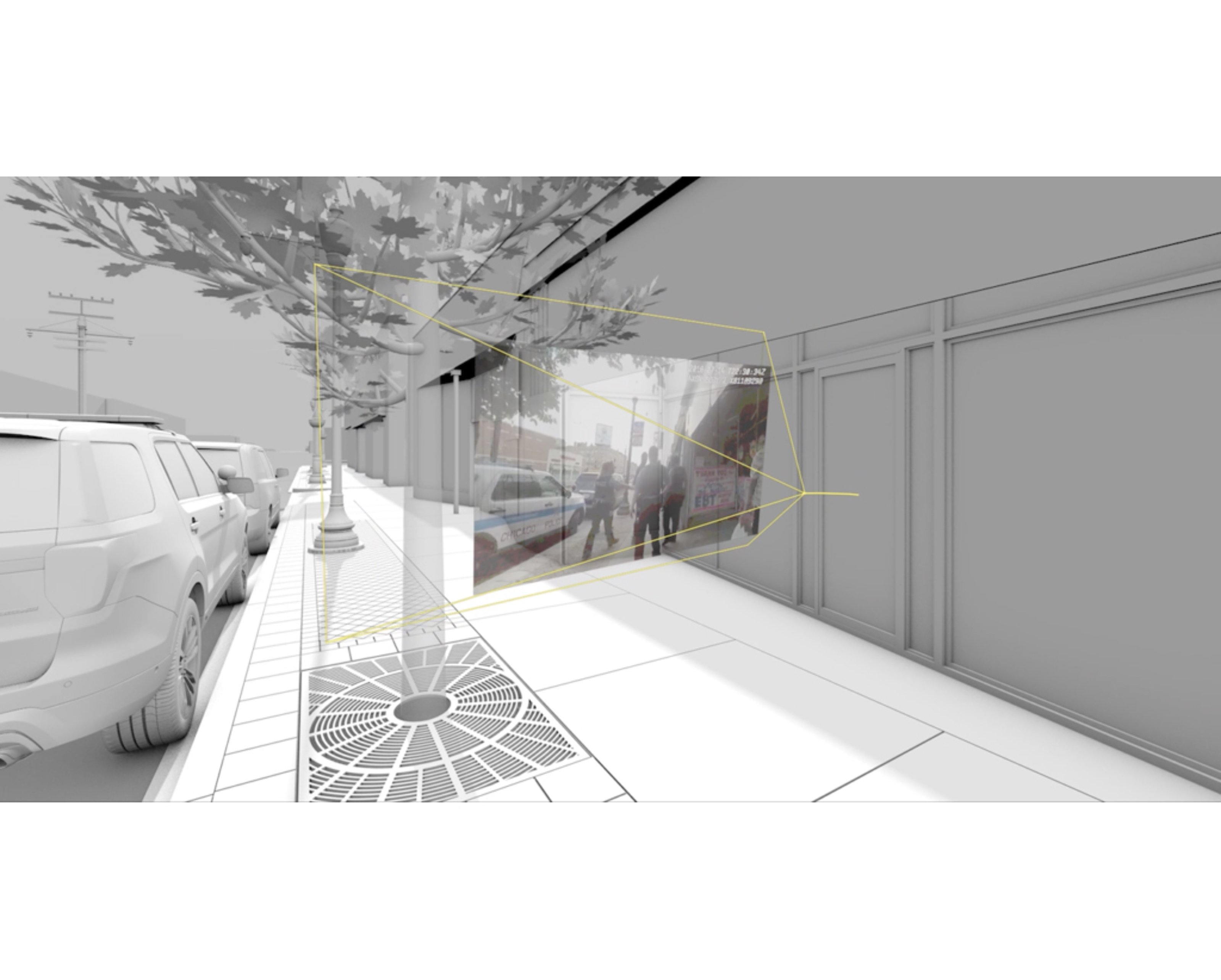

Forensic Architecture – Triple Chaser, 2019

EW: It is always our intention. Each one of the cases does two things. Look, our resources are limited. We’re a group of 20 filmmakers, lawyers, architects, artists, environmental scientists, you know, an archeologist, a journalist. We’re a small team. We take exemplary cases and our aim is always two things: one is to serve the stakeholders. In the Mark Duggan case, it was the family of Mark Duggan, particularly his mother that commissioned us through their lawyers. So they are our primary stakeholder. We do the work for them out of respect for the decades long way in which the state completely neglected and did not respect them as people and their demand for justice and accountability.

But secondly, every case also shows an opportunity. It’s a window towards how things could be done. A lot of our cases spend a lot of time showing how we do what we do. That is to say how this could be replicated. There’s a model. There’s nothing here that is science fiction. It’s complicated, but you know, it is replicable. We are now establishing groups in Hong Kong. I was brought to Hong Kong when the protest began in last summer a year ago.

About, five, six different groups connected to the social movement and the protests contacted us, Forensic Architecture. They asked us to come, to investigate . I traveled there just before COVID. I think I was there in December. I saw the eagerness. I saw the commitment. I saw the ability there, and I said: “you don’t need us.” We would support you with advice, but you would make your own investigation. You would investigate your own government. And that would be a power to demonstrate that the citizens are not simply governed, but can speak back with the tools and techniques. And indeed, we base it around the studio in an architectural faculty with Amy Chong, who’s an artist there. And we have built a collective that has now produced extremely important evidence for the abolition of tear gas as a weapon.

And this is a model we are increasingly operating with. Anyone that comes to us and says: “We want to learn or be supported, we will help them establish a group. In France, we established a group around race-based violence. In Turkey, I’ve myself traveled to Diyarbakir to discuss this with some people. There is a group in Turkey called Forensic Architecture run by Pelin Tan and they’re doing similar work. We don’t need to keep anything proprietorial. In fact, everything that we know how to do, we don’t need to do. We only take cases we don’t know how to do. Mark Duggan was a very interesting case. For a year we investigated a second, one second, between when Mark Duggan leaves the cab and when he was shot, without videos. Everybody told us: “Oh, you need videos. It’s all about video.” There was not one video, not one video. There were 11 testimonies. And we looked at them, there were 500 pages of testimonies that we broke down to minutiae of time that we synchronized, that we looked at together. It’s not video. It’s not even that there is a technique. It’s just the eagerness and commitment to investigate. The aesthetic field has in it, the sensibility, the intelligence. In the field of art and architecture, there is enough intelligence and commitment to be able to do things differently, to investigate differently.

We’re not replicating police tactics. We aren’t even interested in how the police do their investigation. We do them completely differently and now police are coming to us, “Teach us. Teach us.” We don’t, we don’t deal with them. They don’t enter our office because we would never work for state agencies.

EO: The conversation around reforming the police departments has been reignited since George Floyd’s murder. The previous wave saw the wider implementation of the police body cameras, which were used to provide an objective truth to the public about police brutality and potentially reduce it. From your investigations, the killing of Harith Augustus specifically, we see that video recordings provided by officials can also be tampered with. The police departments across the US converted a control mechanism that was implemented to benefit the public to something that is being used by the police to justify brutality. I believe though, with the integration of blockchain technology and strict measures, it is possible to create transparency and accountability. What do you think is a way to achieve true transparency between the police and the public?

EW: There is nothing like true transparency. There’s only struggle. I can only promise you struggle and more struggle and more struggle. There is no system that will solve it all. Of course body cams provide information, but they also open the way to new kinds of manipulation.

When I showed the mother and aunt of Mark Duggan the Harith Augustus investigation, they said something very important. They said body cams are directed in the wrong way because the body cams are not filming the policeman but instead are filming what is called the suspect.

In fact, what we need is body cams watching the police. And of course this is the activist cameras, like the program called Shooting Back. And today we are witnessing new calls for the rebuilding of the Black Panthers as a community force that would need to be there and hold the police accountable.

There is no way that policing as we conceptualize it today is the right answer and need to be supported with anything. Policing has to change. The idea of safety and security of vulnerable people in our communities need to be addressed completely differently. And until that point, we need force to protect us from the police.

And I completely understand that we need people following police with cameras, recording what they do, standing there, not allowing them to abuse their power. That by the way, was one of the foundational principles of the Black Panthers, protecting communities from the police.

EO: Absolutely. Thank you. So are you guys receiving any requests for investigations from the U.S.?

EW: We are working on other project of police violence, not only in the US but worldwide. And we will continue to do that under our split-second methodology. Thank you very much!

EO:Thank you so much for taking the time. Have a great day. Thanks.

EW: Bye, bye.

EO: Bye.