Berlin-based architect Arthur de Ganay resides in an abandoned jam factory that’s been converted into a home for him as well as an exhibition space for his art collection. Here, de Ganay organizes private tours, showcasing a dozen works at a time. A fan of architectural photography, the architect chats with Collecteurs about his unorthodox living space as well as his fascination with the work of artists like Hiroshi Sugimoto, Thomas Ruff, and Candida Höfer—all devoid of human representation.

Collecteurs: You’ve stated that it was your encounter with the photographic oeuvre of Hiroshi Sugimoto in 1995 that persuaded you to start collecting contemporary art. Can you tell us a bit about that experience?

Arthur de Ganay: It was a very personal experience discovering Hiroshi Sugimoto, surprisingly on the street where I grew up and lived in Paris: Rue de Lille. This street is not unknown to the art world; the Musée d’Orsay opened there in December 1986. I was only 13 at the time, but I witnessed the conversion of an underused railway station to a stunning art and architecture museum, almost in front of my own door.

Ten years later, in 1996, as an architecture student, I moved one street away, to Rue de Verneuil, and I was often around Rue de Lille, where almost by chance I stopped by an exhibition I had not heard of or read about. The exhibition was in an inspiring space with a large glass roof in a courtyard. There, I admired the strongly conceptual “Seascapes and Theaters” series by Hiroshi Sugimoto, and even if I could not afford one of them at that time, it drew my attention to photography as an art that is worth the cost of being collected and exhibited.

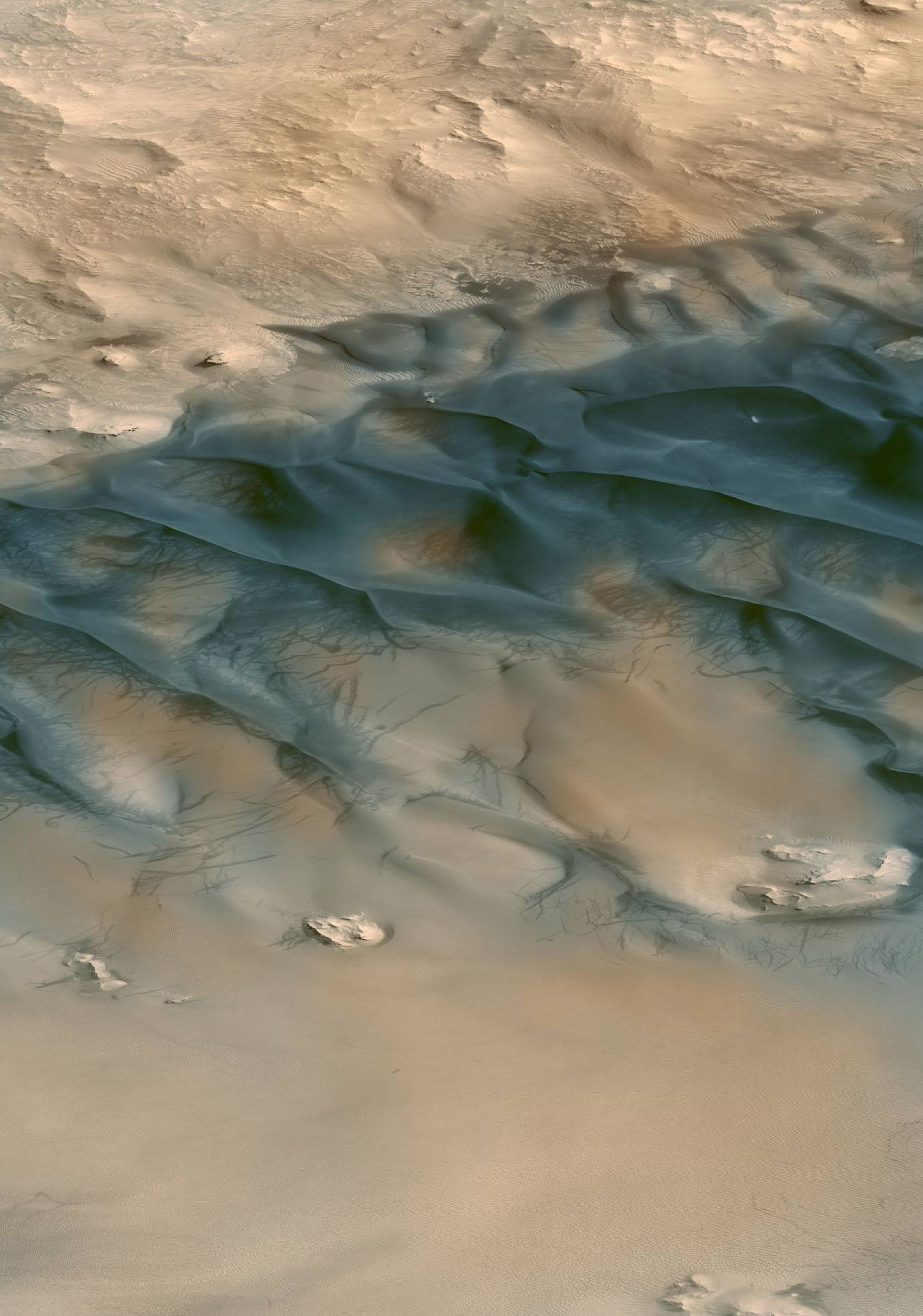

Artwork: Thomas Ruff – ma.r.s. 15, 2011

How have your collecting habits evolved since then?

Well, as I remember, Hiroshi Sugimoto had not begun his architecture series—which became my favorite works from him by far—by 1996. As far as I know, his works had not been printed in large format before 2000. The blurred architectural views that Sugimoto has created since then are the strongest ones to me because they have this smooth pictorial quality, which brings photography much closer to the art of painting, in a way that only sharp and realistic photographs can achieve. Sugimoto wrote that he wanted to reduce the architectural form to the essential volumes that structures are made of. To me, this reduction and removal of details are directly linked to impressionism because it requires the viewer to make a real effort to imagine, to complete the missing information.

In the Charles Riva Collection last year, we tried to underline the mysterious strength of contemporary photography by exhibiting Hiroshi Sugimoto’s architecture series together with the “Mies van der Rohe Serie” by Thomas Ruff, along with Sugimoto’s “Theater” and “Paris Opera” by Candida Höfer. It was very intriguing to observe the silent force of these large prints and how they unfolded themselves within this monumental space, which was partially painted grey specifically for this exhibition.

Artwork: Thomas Ruff – l.m.v.d.r. w.h.s. 10, 2001

What was it that drew you to photography enough to base your entire collection on this medium?

After I completed my Master of Architecture at Georgia Tech in Atlanta in 2000, I received my Architecture Diploma in Paris in 2001 and then moved to Berlin, where I am still living and working today. In March 2002, I discovered architecture photography from the series that Thomas Ruff created for the “Mies in Berlin” show, which was exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art New York. Ruff experimented with old pictures he received from the Museum mostly by coloring them: it struck me because it was a highly subjective and interpretative view on architecture, which is much closer to art than photography normally is.

In September 2004, I came across the photography of Lewis Baltz in the Berlin Art Fair and I bought a photograph from his “Sites of Technology” series. I found his work particularly interesting due to the high degree of abstraction in his representations of clinical modern interiors.

I encountered the art of Elger Esser for the first time in New York in April 2006, and I have passionately collected his works since then. To me, Elger transforms the art of landscape through the strength of large and mostly sharp, contemporary photography. But what I found even more interesting was his use of old hand-colored postcards. In this series, he enlarged these postcards and printed them more than 100 times larger than their original sizes. As a result, the landscape became blurry and painterly, thus resembling a painting.

You converted an old abandoned jam factory into a home for yourself and your art collection. How did it come about?

I acquired two lofts in the so-called “Marmeladefabrik,” which went through a renovation process between 2004 and 2006. The beautiful location directly facing the Spree River convinced me to use the first loft for living and the second as an exhibition area where the photography collection was exhibited from 2006 to 2016. Later on, in 2017, I furnished the second loft and started offering guided tours again, but less frequently this time since it now also served as a living space. Now, I exhibit only 12 artworks there instead of 18, as it was until 2016.

Since you’ve transformed your living space into a curated exhibition area, organizing and guiding tours, how do you incorporate the intimacy and curatorial approach into your exhibitions?

Until 2016, the second loft was dedicated only to artworks. The lack of furniture allowed me to create a stronger curation here. Having a silent atmosphere and enabling visitors to contemplate the underlying value of art was an essential motive for me. I also paid constant attention to lighting and reflection, which are very important for photography and often overlooked by exhibitors.

In 2012, I opened a show with two artworks from the “ma.r.s.” series by Thomas Ruff. Prior to this exhibition, works from this series were mostly exhibited in white cubes, which might induce their resemblance to paintings. But after reading about how the artist reflects upon this particular series, I felt that the painterly approach was not exactly—or maybe not only—what these pictures meant for him. To me, they are surfaces of Mars that should be examined in depth as landscapes. I exhibited the works in a way that resembles the darkness of space and that positions the viewer as a rocket man approaching Mars. To create this illusion we installed two black cabinets, one for each work.

The physical presence of interior spaces is essential in Candida Höfer’s oversized representations of these spaces. Also important are socio-cultural associations, as well as the effects of architecture and space on humans. Paradoxically, this effect is often created by the very exclusion of humans from these photographs. As an architect and collector of Höfer’s works, how are you inspired by her approach to interior spaces?

The interior views by Candida Höfer are mostly poetic: To me, the third dimension or the depth of perspective becomes a metaphor for the past and the history of the structures her works represent. However, I feel that the works from “Paris Opera” are rather more spectacular than poetic due to the stunning architecture designed by Charles Garnier, and the building itself, which is very carefully conserved and resides in overwhelming unity. In this sense, I find them quite unique, but I might be biased since I grew up in Paris.

The exclusion of human representation from the photographs I collect is essential for me, and I relate this concept to “__The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” the influential text from Walter Benjamin. The author wrote: “But as the human being withdraws from the photographic image, exhibition value shows its superiority over cult value for the first time.”

Artwork: Candida Höfer – Opera Garnier Paris VII, XXXI, 2005

End.