Collecting art comes easy to someone like Ryan Kortman, and that’s not because of a bank account with extra cash to spend. On the contrary, the former painter avidly explains his economic past and present, how the debt of his former studies at SAIC made him realize that, after all, money is a real thing, and a stable income needs to be had in order to, well, live. Yet, leaving the art world was never an option to Kortman.

While he’s creatively active as a video editor for an advertising company, Kortman spends as much time as possible tending to his collection that primarily focuses on supporting young artists. When Kortman speaks about his obsession (he himself calls it that), it doesn’t take long for him to address the restraints and honest concerns that come with such a costly occupation; he isn’t exactly broke, yet spending $1,600 on a piece he recently fell in love with isn’t an overnight decision. It might take months, sometimes years. There have been times he has been fortunate enough to buy directly from artists, or come in contact with generous dealers who offered discounts and payment plans. Unable to jet-set between art epicenters like New York or Los Angeles, the Chicago-based collector has been buying most of his works online for over 11 years. The moment the packages are delivered, is the very first time he gets to physically experience the work.

For Kortman, collecting art isn’t about investment. Nor is it about the entry to certain social landscapes of prestige where perfectly-chilled champagne becomes one of the lesser exciting things on the list. His daily consumerism revolves entirely around art and art itself, sometimes seemingly close to the point of existential peril. To all of this there’s an underlyingly-humane outcome; Kortman has ultimately quietly renounced his artistic aspirations in order to support those of the other; a type of accidental martyrdom, completely met by instinct, which only furthers him as a true proponent of art. Kortman’s straightforward relationship is a fully-consumed humanistic portrait in its sincerest form, reminding us how art doesn’t necessarily need to remain as an objective of the super elite, but—in all its current actuality—is there to be devoured by anyone.

Collecteurs: You’re a trained artist yourself. How does this part of your past influence your collection, and collecting practice?

Ryan Kortman: I studied painting and drawing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. During that time I was introduced to the work of the Chicago imagists. Their work was influential to me and I think that particular influence is apparent in a lot of the work I collect. SAIC provided a first class art education, but it came with a price. The mountain of debt that was piling up was never far from my mind, so I decided to pursue a field that offered a more structured road to employment. Looking back I think my experience has a direct correlation to the importance I place on supporting artists at an early stage in their career.

C: If it wouldn’t have been for a mountain of debt, do you think you’d paint for a living now? Money, it’s an unfortunate reality…

RK: I’m not sure that I would have continued as a painter specifically, but I definitely would have pursued a life as an artist. No other profession offers the freedom to pursue ideas in the same way.

C: And no other profession is as existentially dangerous as that of the artist… Yet, you did study painting, despite the economic repercussions. If you had the chance to go back, would you study painting all over? Or would you have chosen a different field of study?

RK: I wasn’t exactly a model student in high school, I had a strong rebellious streak and some issues with authority. My perception was that art school offered an environment that was more conducive to my way of learning. SAIC was a great fit because the undergraduate program was interdisciplinary. I was able to explore other avenues while having the credits all count toward my degree. I was aware that sustaining myself as an artist was a long shot, so I was always trying to think of how I was going to make my art education work in a practical way. I eventually found a home in the video and animation department, which is where I learned the skills I use today as a video editor. If I had to do it over again I would not change anything.

C: What drew you to the video and animation department, considering it’s a different artistic outlet to painting?

RK: I started making videos with my younger brothers when I was twelve, mostly as a form of entertainment. This was before nonlinear editing was introduced, so the editing was done in camera, or with two VCRs when I was feeling ambitious. Dealing with time and rhythm was something that came natural to me. When I started taking video classes and was introduced to the proper methods it was like learning a new language, but for a method of communication that I already understood.

C: How (if so) does the method of communication change from painting to video?

RK: I liked the fact that video incorporated a moving image with sound, more of an immersive experience for the viewer but also maybe more fleeting. The static nature of painting and sculpture offer a permanence that is more attractive to me as a collector.

By the window: Lukas Geronimas – Custom Tub (1), 2015 – © Emilia Jane for Collecteurs

C: What do your relationships with other collectors look like? Do collector trends influence your buying habits at all?

RK: I probably have more in common with my mechanic than with another art collector. I’m not rich, so for me collecting art requires significant financial sacrifice.

I rarely travel which creates a type of social isolation that works in my favor where trends are concerned. I’m simply not aware of what other collectors are talking about.

C: So you try to stay away from trends? What would generally be disconcerting about being aware of trends? Would it disrupt or influence your decision-making in terms of collecting, and inherently become more about the possibility of investment?

RK: For me, collecting art is much more than being able to identify and follow a trend, it is a way of self expression. It’s cool to see some of the artists I approached five years ago achieve success in the art market. I feel like a small participant by being involved early in their career.

When I started collecting, artists who recently graduated would be eager to sell work directly at what I would consider a very fair price. Now everyone has representation and the prices reflect this new reality where everything is $8-10,000. I do not know whether this is a good or a bad thing for art but it definitely makes it more difficult for a collector like myself.

C: Where does this innate love for objects come from? What is it that makes objects—in this case, art—so absolutely vital to be surrounded by?

RK: Like many kids from the 80’s I started collecting stickers and later sports cards. Going to the local card dealer was like a religious experience and I had no problem spending everything I had there. I can remember a visit where the only thing I had left was a two-dollar bill and without a second thought spent it on a must-have Bo Jackson rookie card. This behavior is unchanged in my adult life, I approach my art collecting with the same fervor.

C: How do you know when you want to acquire a work personally?

Most of what I collect comes from images I see online. There is not a great deal of research that goes in to it, mostly impulse, which has served me well.

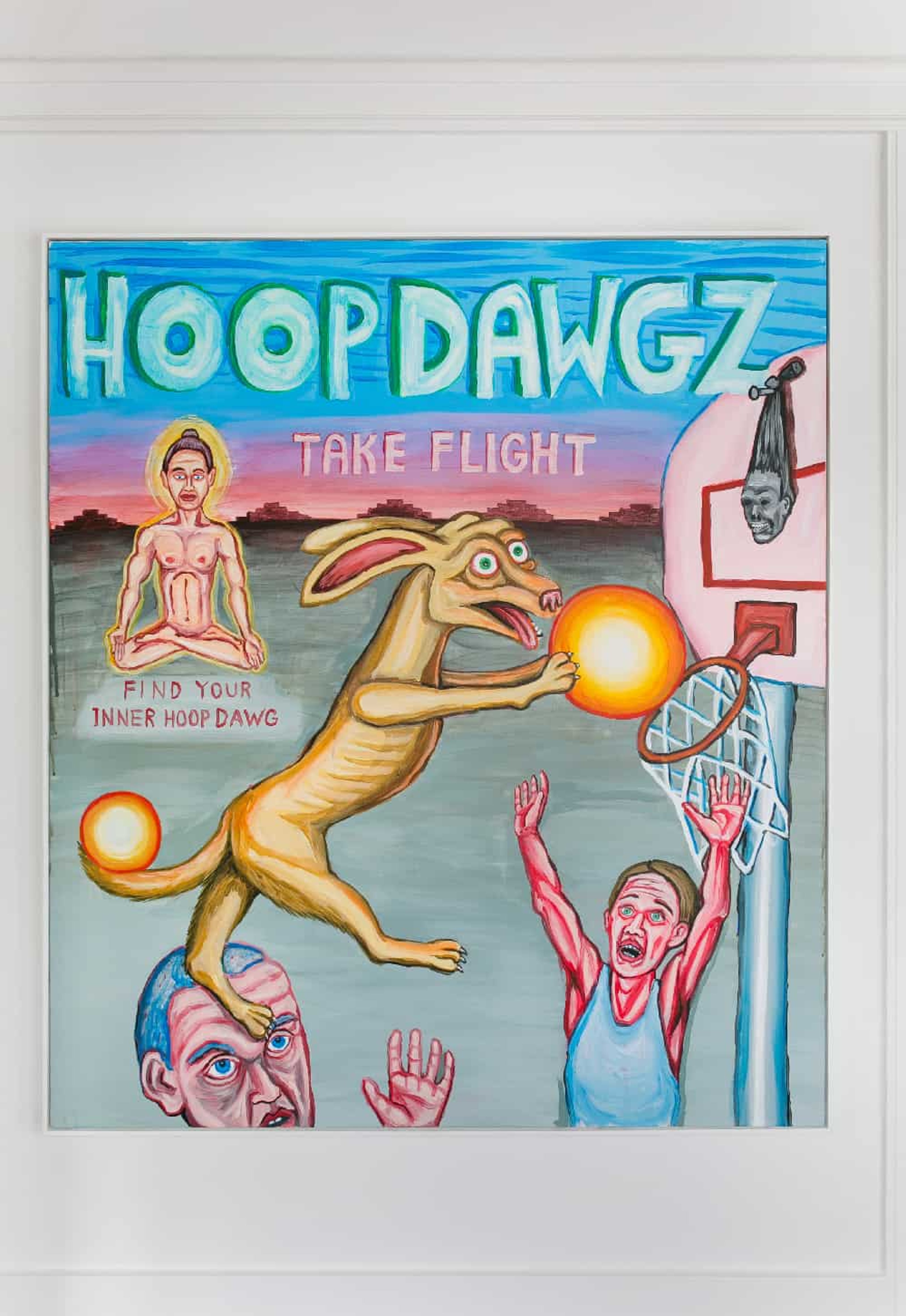

Ian Hokin – Burn in Hell Motherfucker!, 2011 & Ian Hokin – Coming Home, 2013 & Cy Amundson – Thoughts on Proximity (Moon Dog), 2012 © Emilia Jane for Collecteurs

I only have two major regrets in all of the purchases that have been made over the years and they were paintings that I saw in person during a studio visit, I think my judgement was clouded by the salesmanship of the artist.

C: Once you’ve spotted something online, is it important for you to see the work in real life before buying, or do you completely trust your online impulse?

RK: Due to the fact that most of the art I am interested in is either being shown in New York or Los Angeles it is rare for me to see something in person before purchasing. 99% of the time I am seeing it for the first time when it arrives at my door.

C: Has that usually paid off well for you, seeing the works only once they’ve arrived at your doorstep?

RK: This is the way I have always operated, so it feels very normal to me. I only have two major regrets in all of the purchases that have been made over the years and they were paintings that I saw in person during a studio visit, I think my judgement was clouded by the salesmanship of the artist.

C: Can you explain a bit about the advisory work you do with Arete?

RK: Unfortunately, the art advisory division of Arete hasn’t found a client base. I am passionate about supporting artists, but I reached my spending limit early on. So I thought that building collections for people who were interested in getting into art would be a good fit. There has always been an allure for me to work in the art world in some capacity, but I have yet to find something that works. I recently started making custom frames for all of our paintings which has been a learning experience. Perhaps I can start a side business as a framer once I refine my skills.

C: When you say that you have “yet to find something that works,” what do you think has been missing?

RK: My experiences in the art world have been very positive. I like having an idealistic viewpoint and I am careful to not introduce something that would compromise that outlook. I compare it to the perils of pursuing a job in a bakery due to the love of the smell of fresh bread. Once you begin to associate the scent with hard work or negative experiences it becomes less appealing. There’s always a compromise to be made.

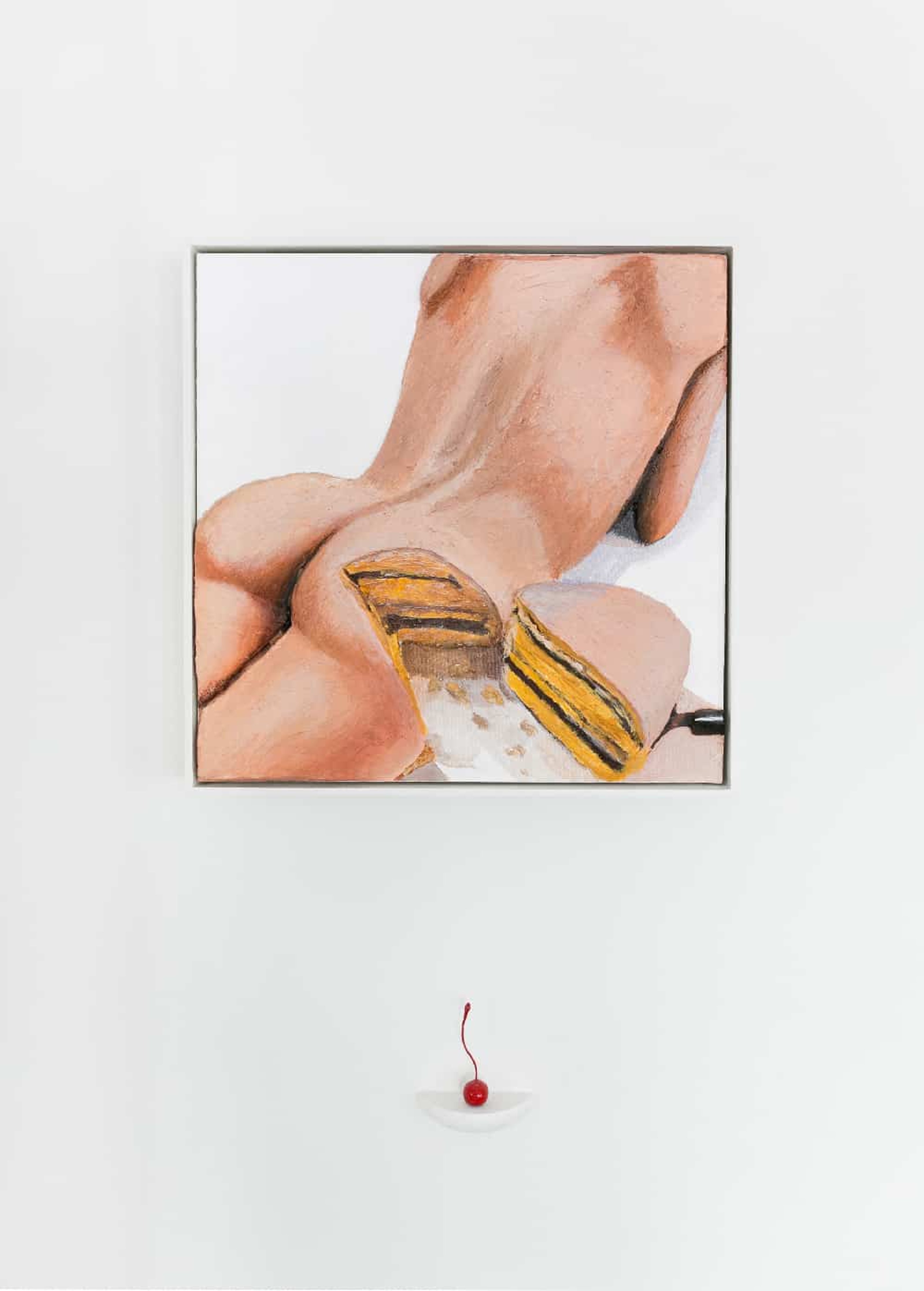

Becky Kolsrud – Group Portrait with Security Gate, 2015 – © Emilia Jane for Collecteurs

C: Some years back you worked as a museum guard at the Grand Rapids Art Museum. What was one of the most rewarding experiences during that chapter of your life?

RK: As a security guard in a small institution I had a front row seat to the inner workings of the museum. I learned that in many cases the works in an exhibition were donated by area collectors and this generosity was of particular interest. For me, it solidified the idea that an art collection was something that was meant to be shared with the public.

C: Was it also the innate experience of witnessing people emotionally transform when confronted with art, that solidified the idea of art collections belonging to the public?

RK: It was more of a personal observation. I experienced the benefits of the museum at an early age by taking drawing classes in the basement. There were also docent led tours through the exhibitions, which really brought the works to life and led to my appreciation for art and artists. Years later as a museum guard it was like having a backstage pass to museum. I was present from the time the paintings were delivered in the loading dock, to the galleries where they were uncrated and inspected by the registrar, to the layout and installation of the show. Once everything was in place and the doors opened to the public I spent eight hours a day in the galleries surrounded by extraordinary works of art, what could be better?

C: Was there something you also learned about the general behavior of visitors at the museum, an observation that perhaps also got you closer to art?

RK: There were many factors that contributed to my start in collecting. After college, I took a job documenting a large, private, outsider art collection. I was really drawn to one of the artists and the individual was generous enough to sell one of the pieces to me. The outsider art world was a good place to start, but it wasn’t long before I noticed the artist is often excluded from the benefit of the sale. I decided to shift my focus to collecting the work of my peers where the investment would have more of a direct positive effect.