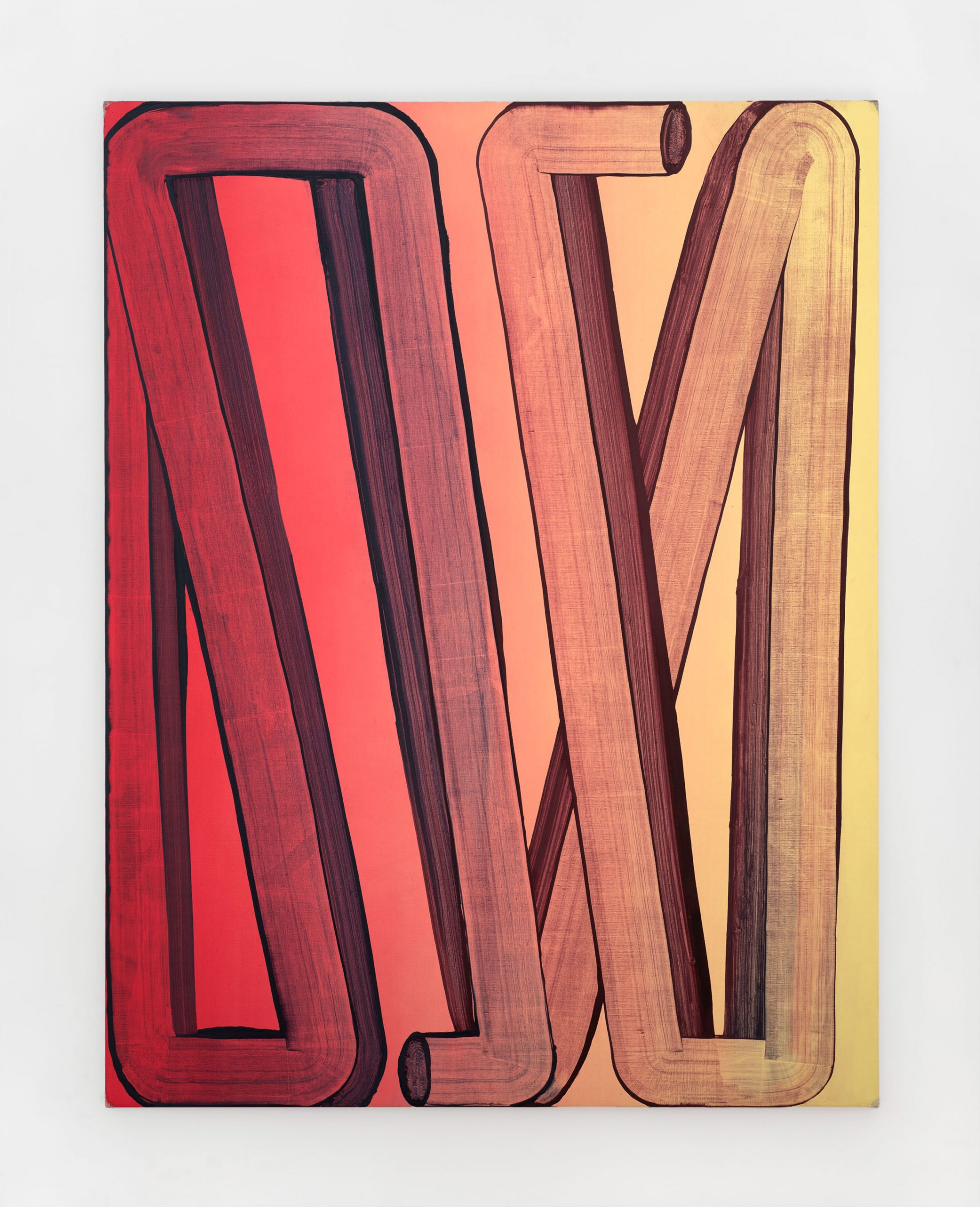

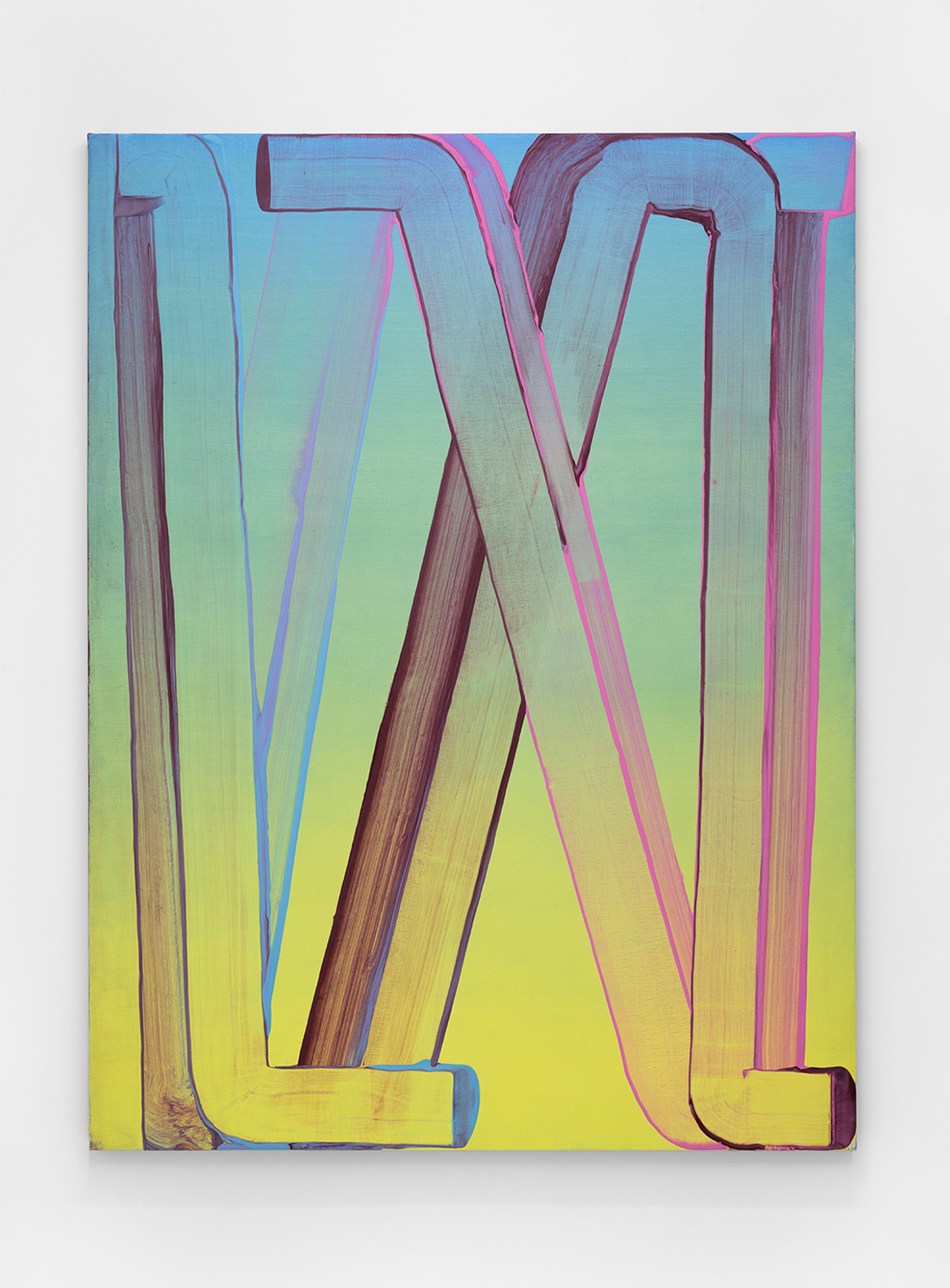

Robert Janitz / Psychedelic Philosophy, 2021 (oil on linen). Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

Robert Janitz is an alchemist of painting. Using a variety of unusual materials like oil, wax, flour, as well as large and bristly brushes from home supply stores, Janitz creates abstract figures that explode with movement and color. Once stating that his paintings were like “buttering a piece of toast,” Janitz elevates the ordinary moments of life to the more mysterious and mythical.

A cultural investigator at heart, Robert Janitz moved from his native Germany to Paris right at the time when Berlin was going through an intense transformation, and the city was becoming the new hot spot for artists. After living over 14 years in France and feeling bound by the contemporary art scene there, Janitz relocated to New York in 2009 and recently again to Mexico.

Collecteurs caught up with Robert Janitz in Istanbul, to talk about the impact of the different cities he has resided in on his paintings over the last thirty years, from the denseness of Paris, the verticality of New York, to the colors of Mexico City. He also shares with us the physicality of various materials he uses, the happy accidents he discovers along the way, and ways to evade performance anxiety when painting.

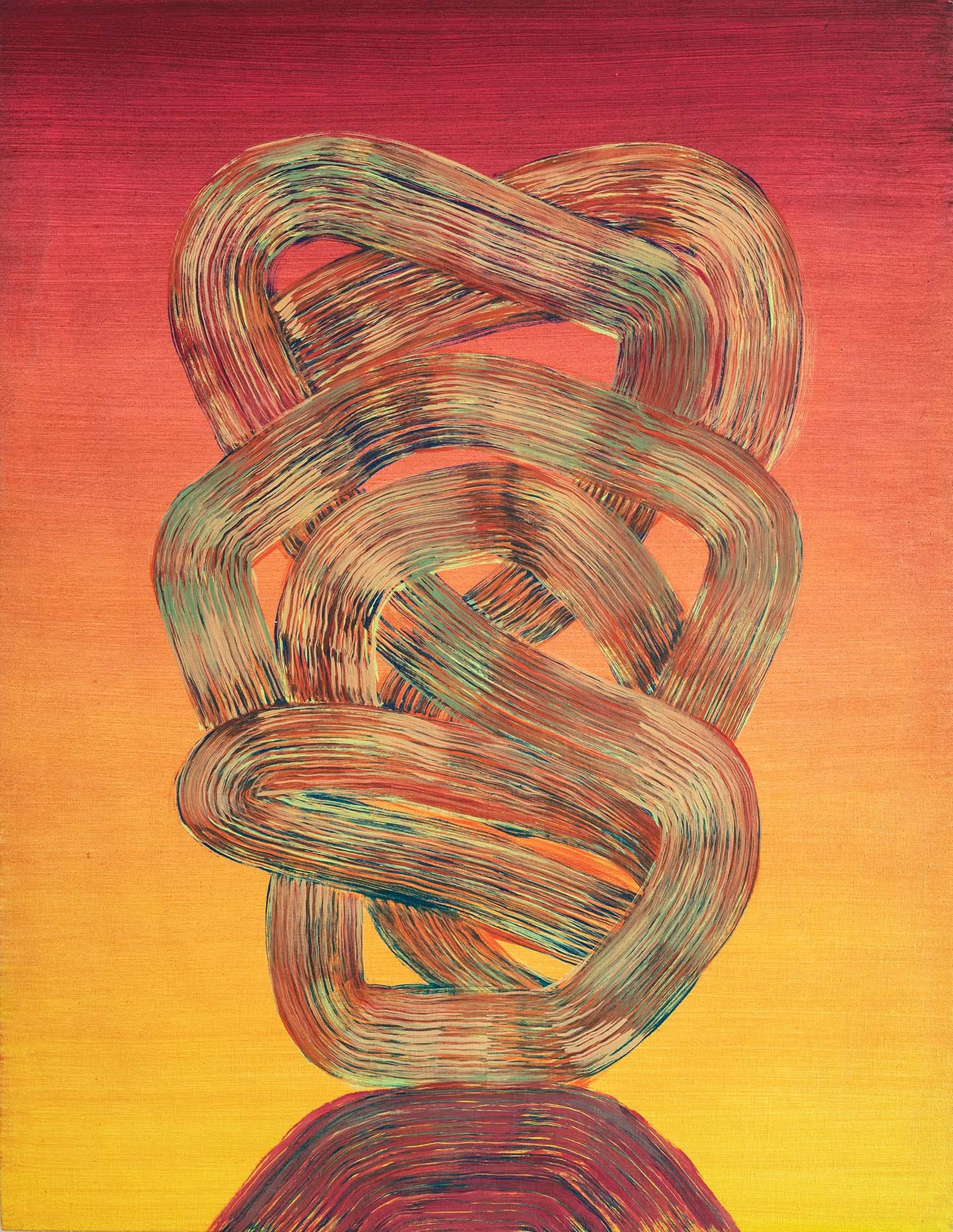

Robert Janitz / Many are the versions of the story, 2021 (oil on linen). Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

Collecteurs: Let’s start with a bit of your background; you were born in Germany but then moved to France in 1994, where you also had your first solo show. Later in 2009 you relocated to New York and just recently to Mexico City. How have these changes affected your work? Do you find that your work reflects the changes within your environment and cultural surrounding? Let’s start with France.

Robert Janitz: That was a long time ago. I had lived in Berlin on and off, so that had already introduced me to the idea of the metropolis. But then I realized there weren’t many options there.

Berlin was a place that, as soon as it became the new capital, it was just a magnet; everybody went to Berlin in the ‘90s. They were all looking for something. And so I figured, if I go to Berlin I’m going to be stuck in how the new Germany is going to be, and I had no idea what that would be. The city was in a process of transformation. I also was in the process of looking and searching. I was already painting but, I mean, in painting, you can go so many ways and you can do so many things. So where do you find something that means something to you? It felt like a mathematical equation with too many variables.

In Berlin, the whole thing was like a mish-mash. I was sort of experiencing confusion. And then I had some friends in Paris and I thought if I go there, at least I will confront myself with something fixed. Paris seemed to be more set in the way that I could grow differently. And it was extremely different—which I hadn’t seen in the first place—but it’s a religious thing in a way, Paris being profoundly Catholic. Not that they all go to church, but the image culture is Catholic. Also historically, it was at the center of the art world at the beginning of the last century.

I don’t know, it’s funny. The French have really good painting, but not now. And I think it’s somehow the fog of Duchamp and the ready-made.

C: And painting shifted to New York, after that, with Abstract Expressionism.

RJ: Exactly, painting somehow left France. And then I was in France. Maybe coming up out of Germany with my German ideas and running into this knife, which is the Duchampian ready made. And I’m thinking: “But I’m a romantic person.”

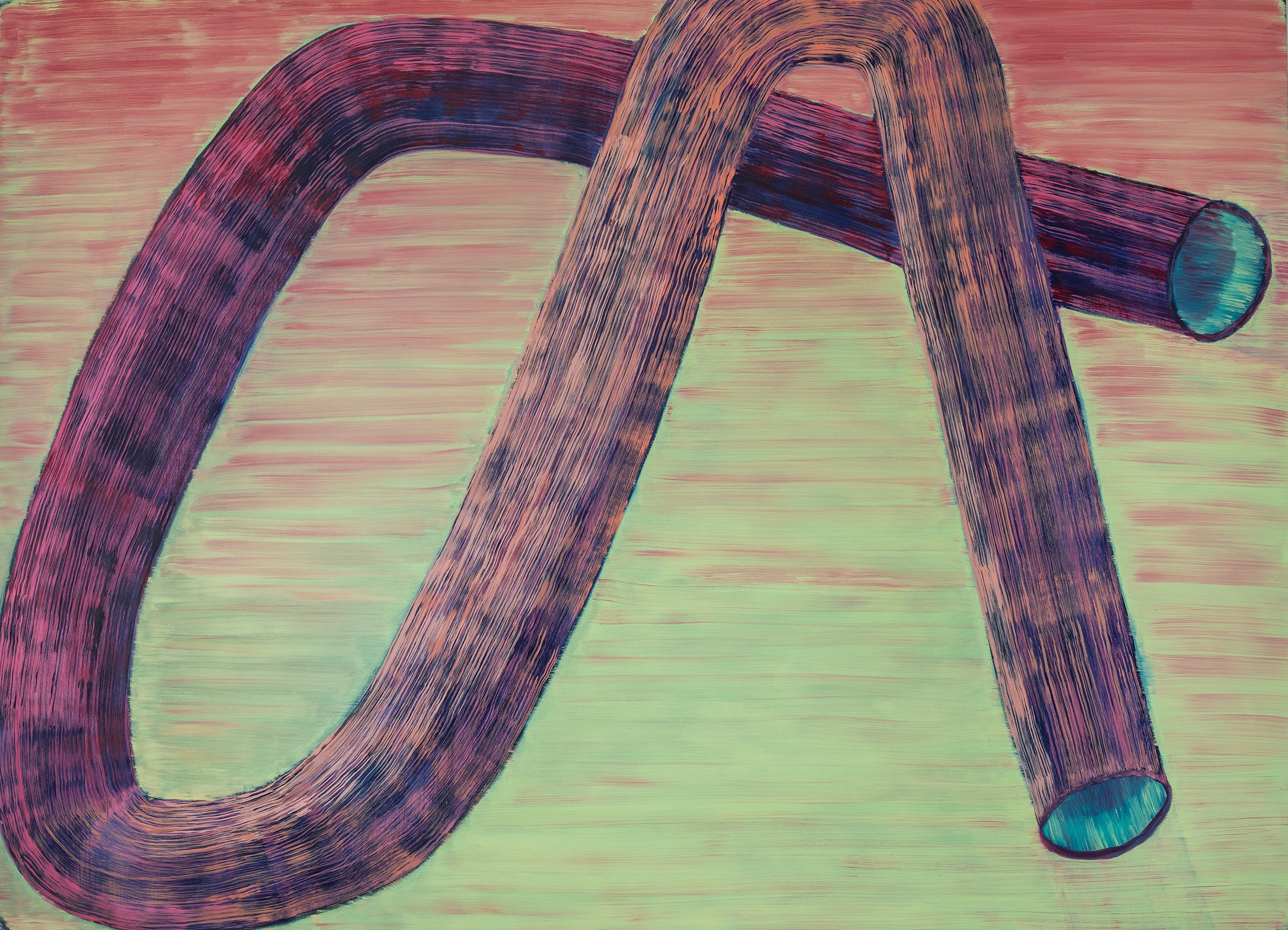

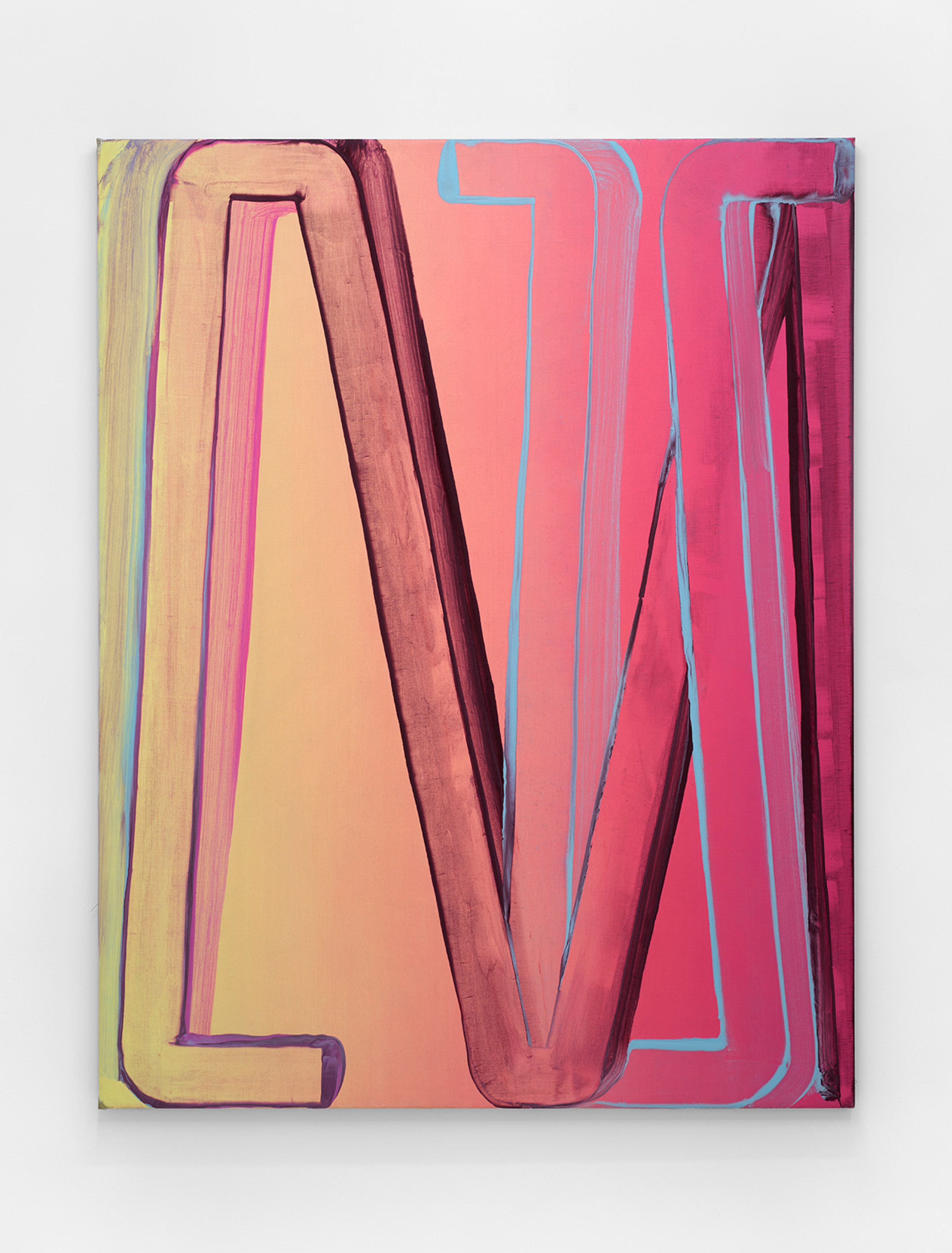

Robert Janitz / Tijuana Moods, 2021 (oil, wax, flour on linen). Courtesy the artist and Canada, New York.

C: So even within Europe, it is different. The traditions of art history are very different.

RJ: Yeah. I mean there are really cool paintings from the ‘50s and ‘60s also, like Dubuffet or Jean Fautrier, who are not really known in Germany.

So I think I just shifted my attention. Instead of looking at German paintings, I was studying more of the French avant-garde. I was actually at some point obsessed with Cubism—which sounds really strange—but I think it had to do with the city also.

You know, Paris is a very dense place, unlike Berlin. Every corner is built and everything’s cramped together. At some point when you have the midday sun, the shadows create these elaborate façades. And I felt like this looks like synthetic Cubism just right in front of your eyes. You just look at it and you get ideas of breaking down a shape in triangles or something. The only kind of open space is around the river. And you’re in this maze of façades, all these façades.

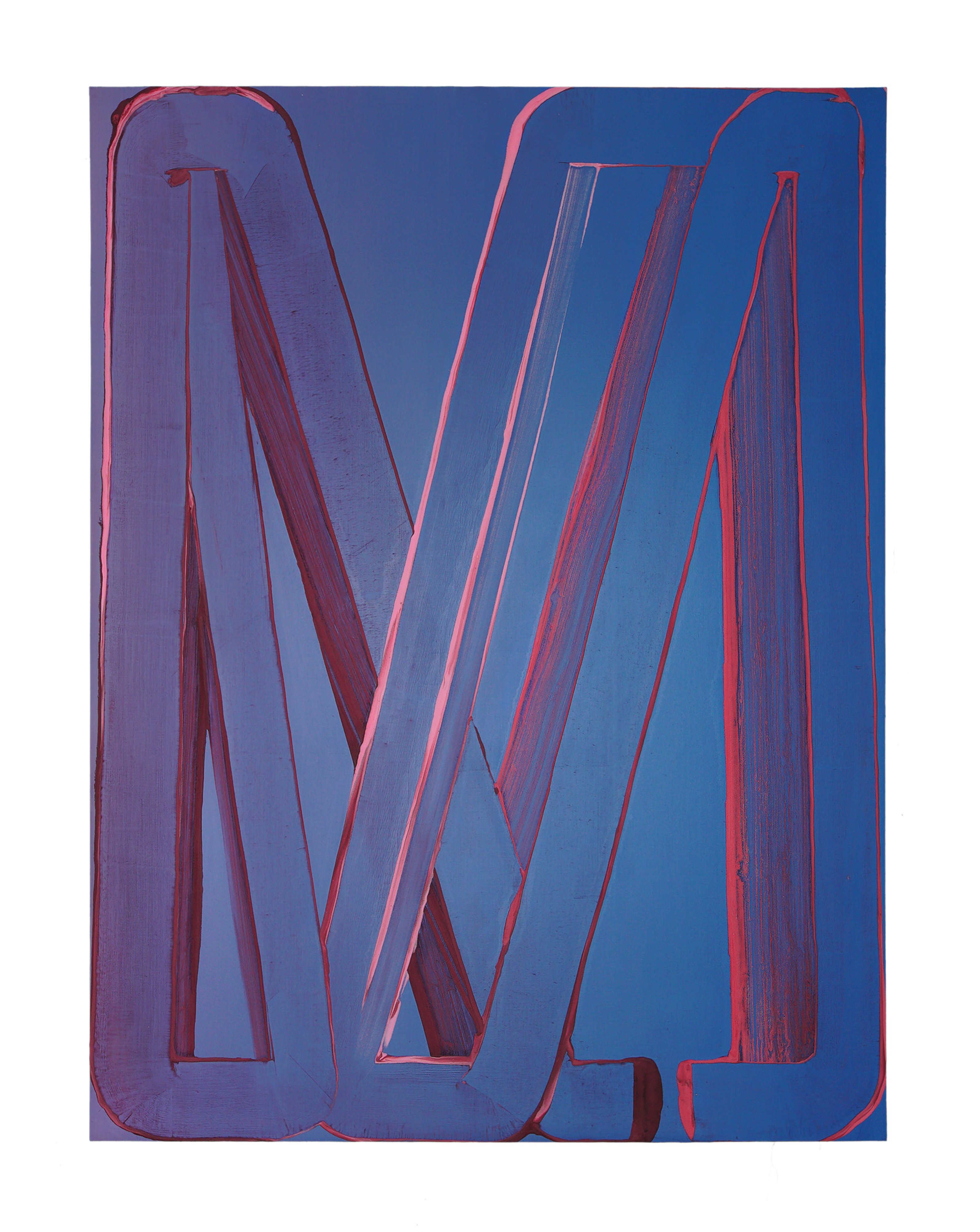

Robert Janitz / Genetic Frequencies, 2021 (oil on linen). Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

Robert Janitz / Magic Realism, 2021 (oil on linen). Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

C: It sounds like painting is influenced by what the artist is surrounded by, in terms of architecture. Now that you are in Mexico, are you observing more open fields, open spaces? Even within the city there must be more light, more openness, more color?

RJ: Also dimensions. It sounds super cliché, but there are a couple of times I remember where I thought; “Oh, this is maybe why I’m interested in painting.” One was an early experience of sitting in a landscape and experiencing it as a landscape, which was a painting in a way. But that wasn’t about light. Later on in France, maybe because the light is different, and also France has the whole Mediterranean side where the light is again, very different. So that was another sort of eye-opener; thinking about all these things you read about light and so on. But then actually in experiences—things all look different.

Robert Janitz / Studying the Samba 2, 2021 (oil, wax, flour on linen). Courtesy the artist.

C: You have said that being in New York brought you a lot of freedom from the restriction of European culture and emotion, its repression. How did moving to New York change your perspective in how you relate to your paintings or just in terms of observing your surroundings?

RJ: I mean, Paris is gloomy in winter and you hardly see the sun for weeks. In New York, it’s cold in winter, but the sky is always super blue. Christmas gives you energy. I mean, I think New York is really impressive because of the huge buildings. I love these bridges—what a fantastic experience. Paris doesn’t give you that. Everything is condensed and low. New York is exploding into the sky.

I think there is something oddly physical about being in the city. Seeing something with just your eyes is not the same as seeing it in person because you are either sitting or you’re standing when you are just seeing it on a screen. It’s another kind of physicality. I am especially drawn to the idea that you stand with your shoulders and your head up and there are tall buildings next to you.

Robert Janitz / The Umbrellas of Cherbourg 2, 2021 (oil, wax, flour on linen). Courtesy the artist and Canada, New York.

C: It makes you feel more elongated physically, because you are in a very vertically aligned space. In an open space you feel more horizontally aligned perhaps?

RJ: I do have issues in super open, empty spaces. I guess it’s called agoraphobia, where all of a sudden that space becomes like gelatin, and I almost feel panicked. But it’s the opposite when you are walking in Manhattan; you feel good as a human walking there. I wouldn’t want to be a dog walking in New York, but being an upright creature there is kind of fun.

Robert Janitz / House plant, 2021 (sheet metal, wood, oil paint). Courtesy the artist.

Robert Janitz / The Mechanik Muse, 2021 (oil on linen). Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

C: Does this kind of vertical physicality affect your paintings?

RJ: I think they deal with verticality a lot. That’s maybe another conversation, but I think at some point the diagonals I introduced came to basically relate to the act of walking. Two legs that are joined at the hip and they do a step.

C: I’ve read that you’re a scholar of Sanskrit as well as comparative religions and art history. Looking at your paintings I see gestures that could read like abstractions of language or letters. Do you think about language when you’re painting? Maybe scrambling words, separating them or bringing them back together?

RJ: I think so. I hesitate to say. When I think of my recent works, the way these lines embrace the edge of the canvas, almost designed for the curve, which is repeating. I accept the rectangle as a frame and that these lines behave within that makes them almost become hieroglyphic in a way. So yeah, totally. Why I’m hesitating to say that now is because I think, as much as I’m curious about my sources, I tend to obscure them to myself in order to protect the mystery of it. I’m afraid that everything is going to dry up and I will have nothing else to paint. I play cat and mouse with myself.

Artwork: Robert Janitz / Time Crystal, 2021 (oil, wax, flour on linen). Courtesy the artist.

C: That is actually an interesting way of thinking. Maybe sometimes we ask artists to explain things too much and that takes away from the mystery of the work…

RJ: I think that’s, again, a cultural thing. This would happen to you in France. You get this Cartesian argument; “What are you doing”? I see the same thing in Mexico. The way they teach art is very much about analyzing, reasoning, finding the links, exploring the links, building links. I tend to think intuition is also valid. The happy accident. But I see all these different strategies for teaching art. It is country specific, or culture specific, too.

Robert Janitz / The Eternal City, 2021 (oil, wax on linen). Courtesy the artist.

C: In that case, let me ask you a broader question about your daily routine with working. I’m sure you’re drawing inspiration from many different sources but what are some things that you find yourself drawn to when preparing to work?

RJ: Now that I title everything and I enjoy finding things very much, that is a big source of inspiration. Whenever I read, I write down a combination of words or a phrase that strikes me. I have a folder on my phone where I write these down. Little by little, I collect these findings. They are unrelated to any painting that may already exist or that will exist. But I just have this basket of words.

I don’t really draw so much, but I think these words are almost like sketches in a way that encapsulates a visual form, which then also translates itself [to painting] intuitively.

Robert Janitz / Ways of Seeing, 2021 (oil on linen). Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

For the longest time, I have been asking myself that same question: “What is my fucking inspiration and what do I actually do when I do it? What gets me started on this?” And I think for years, I was basically sitting around all day until five in the afternoon. I would then finally make up my mind. So I have no idea. This is all probably self-doubt. How big of a deal is mark making? How afraid am I to see the process grow?

C: There must be hesitation before the first mark. Does it become easier afterwards?

RJ: I remember I would think: “Maybe I’m good at writing.” And then I would start my novel and say: “You basically have one word. It’s already a big deal, and then you put another word, and if you add more you have a phrase.” Then you realize, this thing can go anywhere. And that wasn’t very helpful.

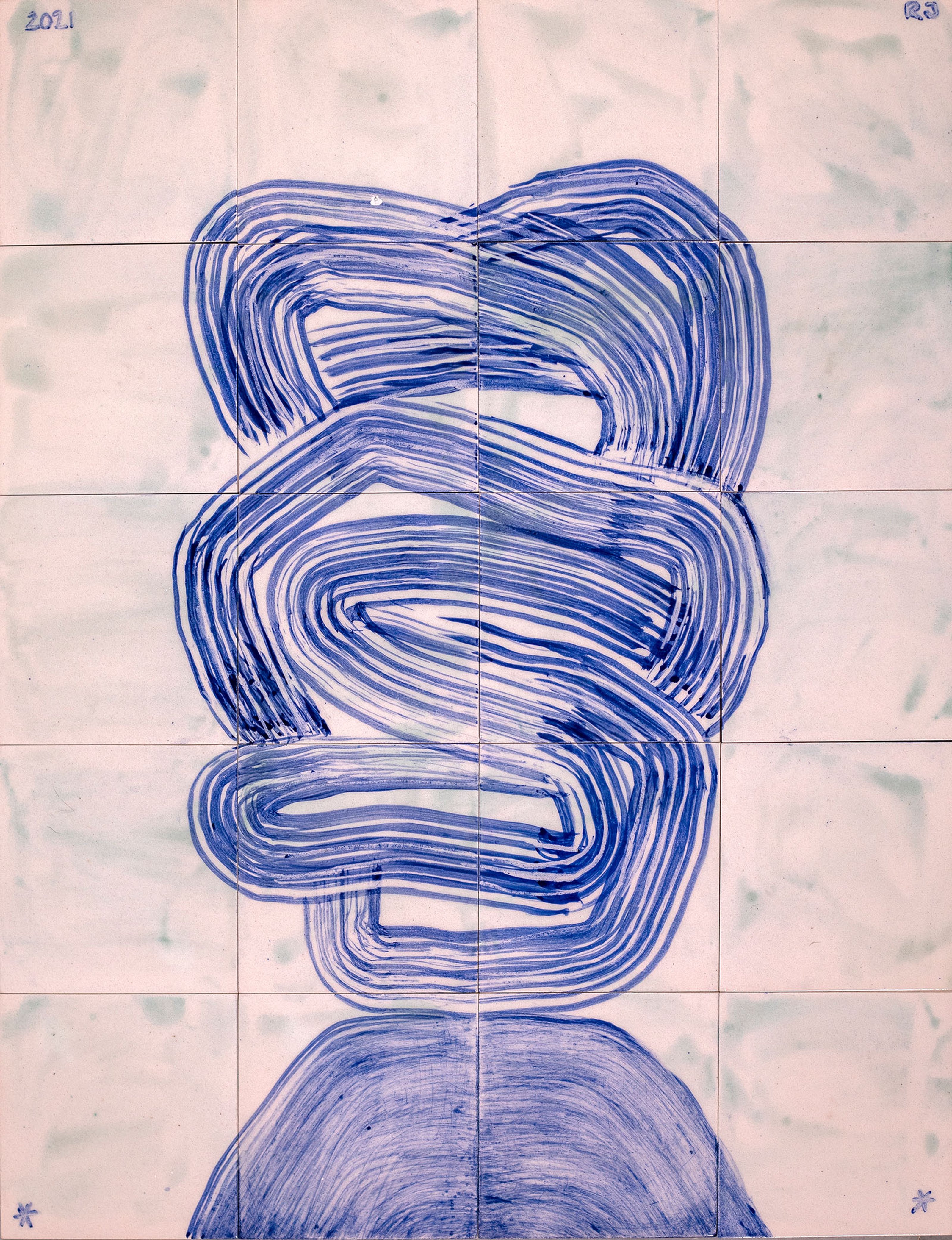

Robert Janitz / Revenge of the Princess, 2021 (oil on linen). Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

But now I sometimes enjoy writing. I also found that acting has helped me quite a lot. Not that I’m very good at it, but somehow you just wiggle around until you find a position where you think, “Oh yeah, I can just say it from this angle.” That helped me get some obstacles out of my head. Now I can even start painting in the morning, which I was never able to do.

I thought I needed to have intense conversations before, and drink a lot, and then maybe the next day, at the end of the day, I could paint. But it’s all much easier now.

C: Speaking of acting, I read that you described yourself painting as taking the role of the “dandy painter.” Who is the dandy painter? How do you see this character within you? Do you treat painting like a performance?

RJ: I guess now I have the image of trapeze artists who can walk on a rope. So I have this ironic observer in me that sees myself playing this role and enjoying it. That takes some of the seriousness out of it. I tended to find it so existential before [laughs]. That’s very German anyway.

C: These actions that you take on the canvas are very visible, your gestures of moving the brush or interrupting with a squeegee speaks a lot on the labor of the painter and how you work. You have described your paintings as “buttering bread” or “washing a window.” How does the labor of painting relate to quotidian activities?

RJ: Again, maybe that’s my whole strategy of creating this fantasy facade of who I really am. Of course when I said “butter the toast” I made fun of this strategy, of the gesture in my painting. But I think I was already aware of it becoming this kind of mythology about myself.

Robert Janitz / The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, 2021 (oil, wax, flour on linen). Courtesy the artist and Canada, New York.

I don’t know, maybe we are back in New York again, thinking about this fantasy of the high rise. I would say I create something about who that person is. I think, of course, every painter does that; you look at the mark, you make the designated painting, and then you have the marks on your palette and at some point they become equally important. Or even the palette becomes more seductive because it has less of your input.

Maybe you’re like a trained dog when making the painting and the real live person on the palette, the conscious and the subconscious. So maybe this fantasy high riser in me, being the dandy painter, playing his role, it’s just a big trope, a façade that is a stand-in for something else. I can build this structure for me and almost believe it myself. It liberates me so I don’t really look at what I really do.

Robert Janitz / Sons and Planets, 2021 (oil on linen). Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

That may be the very inner way of reflecting on myself but at some point when you start seeing yourself from the perspective of another country, another culture, you don’t stop there. With every language, I also acquired a different me, sort of. Maybe that’s where this actor originates. You switch personas. Ultimately, is there anybody at home or is it all just an empty shell that you try to desperately stuff content in?

C: So you find yourself experiencing and observing different cultures to reflect something different about yourself as well?

RJ: One of the main tasks of culture is probably to rein in emotion. A fine intricate structure as a channel. People are not concerned when they are in this kind of untamed wild state—you know, the savage. I feel very savage somehow. [laughs]

C: Maybe that’s also the artist’s state of being too, because you always find the need to delve deeper into your own emotions and the emotions of people around you, the surroundings. Is it about finding yourself within that raw emotional state?

RJ: Yeah, for example, when you write you are dealing with a different grip on the world, because you’re dealing with it when you have your words already. And I think painting is before words. You deal with it without even shapes existing. Shapes may arise, but the whole thing is much more [abstract]. The poet may be closer to a visual painter than to an essayist.

Robert Janitz / Invisible Birds, 2021 (oil on linen). Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

Robert Janitz / A Mathematical Object, 2021 (oil on linen). Courtesy of the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

C: Let’s talk a little bit about the unconventional materials that you use in your paintings; like wax, flour, eggs and hardware brushes. How did you first come about using these materials and what do they represent to you in terms of the physicality of the work?

RJ: Yeah, you go to the art supply store, you buy your paint and you buy your artist’s brush and you buy your little artist’s canvas, and then you make art. Of course, that’s not how it works.

Robert Janitz / Night Flight, 2021 (oil, wax, flour on linen). Courtesy the artist.

Well, I thought to myself, if I do this on a limited rectangular surface where is the freedom to explore? And I guess I’m exploring mixing my own stuff while also using my recollections. I remember at some point I was already experimenting with wax and turpentine and I had this whisk and then I thought it was exactly like when I was a kid and we were making pancakes. And then it gave a whole different idea of what’s happening. I’m not making art, I’m actually back in mommy’s kitchen and it became much more fun and playful in a way. That’s where the flour also came in, and I said “Why not use flour?”

One thing I found exciting when I started using flour was that I realized it chemically reacts within a day or two after applying the paint mix. The paint itself transformed. So there was something happening outside of me.

Robert Janitz / Solace of Round Things, 2021 (oil on linen). Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

C: I was wondering about that too, does the flour mix change over time as it stays on the painting?

RJ: Once it’s set, it stays stable. People ask, “How reactive is that organic material?” Wax is an extra good preservant; the flour wouldn’t get moldy or anything. I basically do something and then it is almost like going with your analogue film into the dark room and then the film finally develops so you see what really happened at that moment. In a way, I find that liberating. It takes a bit of the performance anxiety away.

C: So is there a little bit of unpredictability right before you apply it, and then you see the process coming through very slowly?

RJ: Yeah, when the paint is fresh, it’s more translucent. The wax is translucent. The flour is not so visible and as it develops, it becomes opaque. It’s a very big change. And it’s like, Christmas is the next day. Everything is on the floor to dry. I put some fans on, I switch the light off and I leave. The next day I come in and I go: “Ah!” I’m now at a point where I can know what to expect more or less. But I guess it puts the emphasis more on the process than on the final results.

Robert Janitz / The Secret Life of Plants, 2021 (oil, wax, flour on linen). Courtesy the artist and Canada, New York.

C: I also wanted to ask you about the surface of the painting. So we have talked about the corners that you deliberately leave empty. How do you conceptualize the surface of the canvas? Is the surface separated from the gestures above? You also use a lot of bright colors or gradients on the surface, what do they evoke in you?

RJ: If we’re speaking about systems, there are a bunch of artists that self-impose a system in order to limit the scope. They only paint on Sundays, they only use their left hand or they only use black and white. I tried the system and I found it unsuccessful. At some point it helps, but then it becomes an obstacle. I then went back to zero. What I did when I first arrived in New York was basically going back to level zero, like a buttered toast. Utter negation in a way. And then I was wondering for a long time; “Is this it?” Does that become another system? Or maybe there’s something of a language that is coming out of it. Like a new visual Alphabet. Once you’re at this level zero, what happens then? Let’s say in mathematics we find zero. How do you get from zero to one?

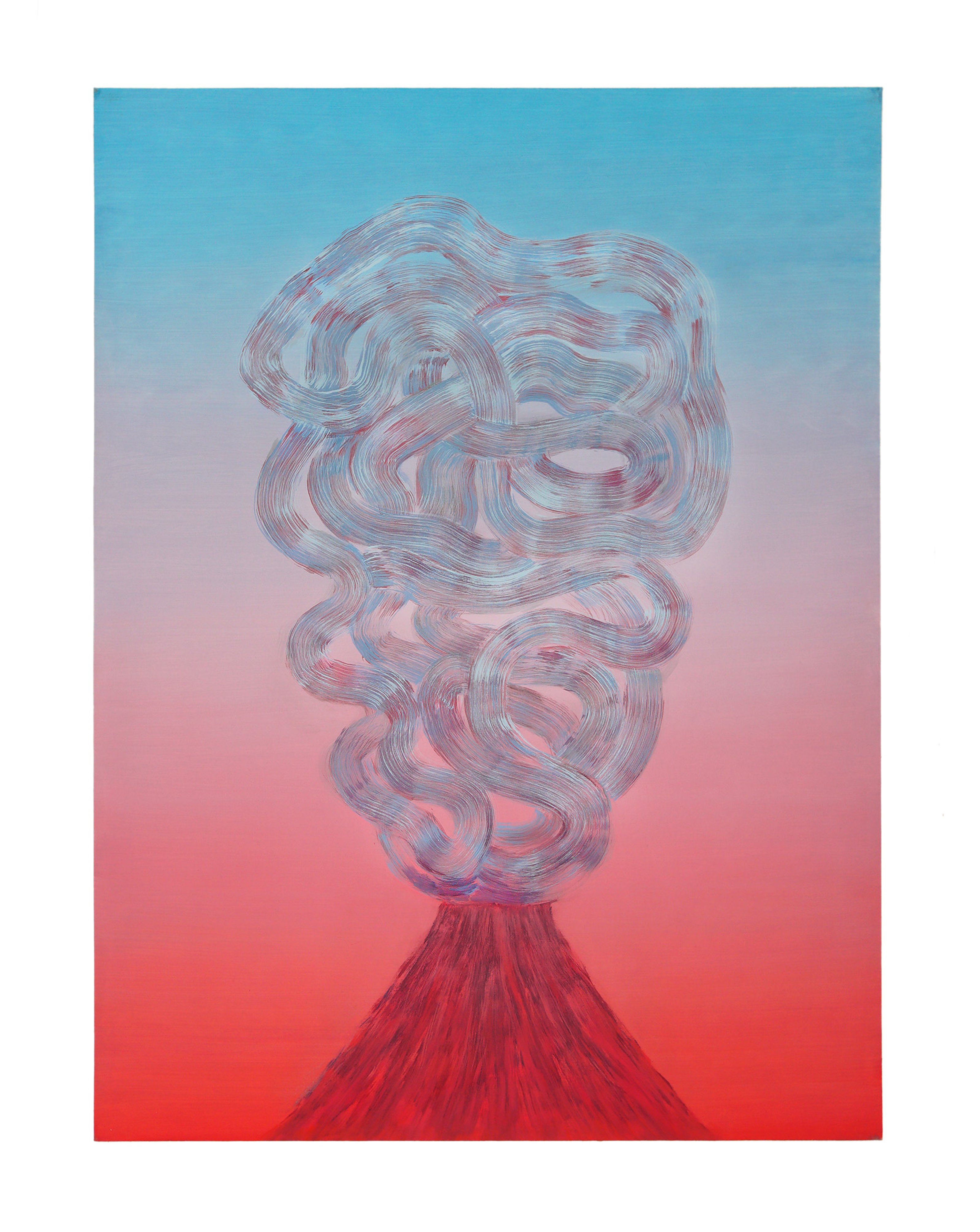

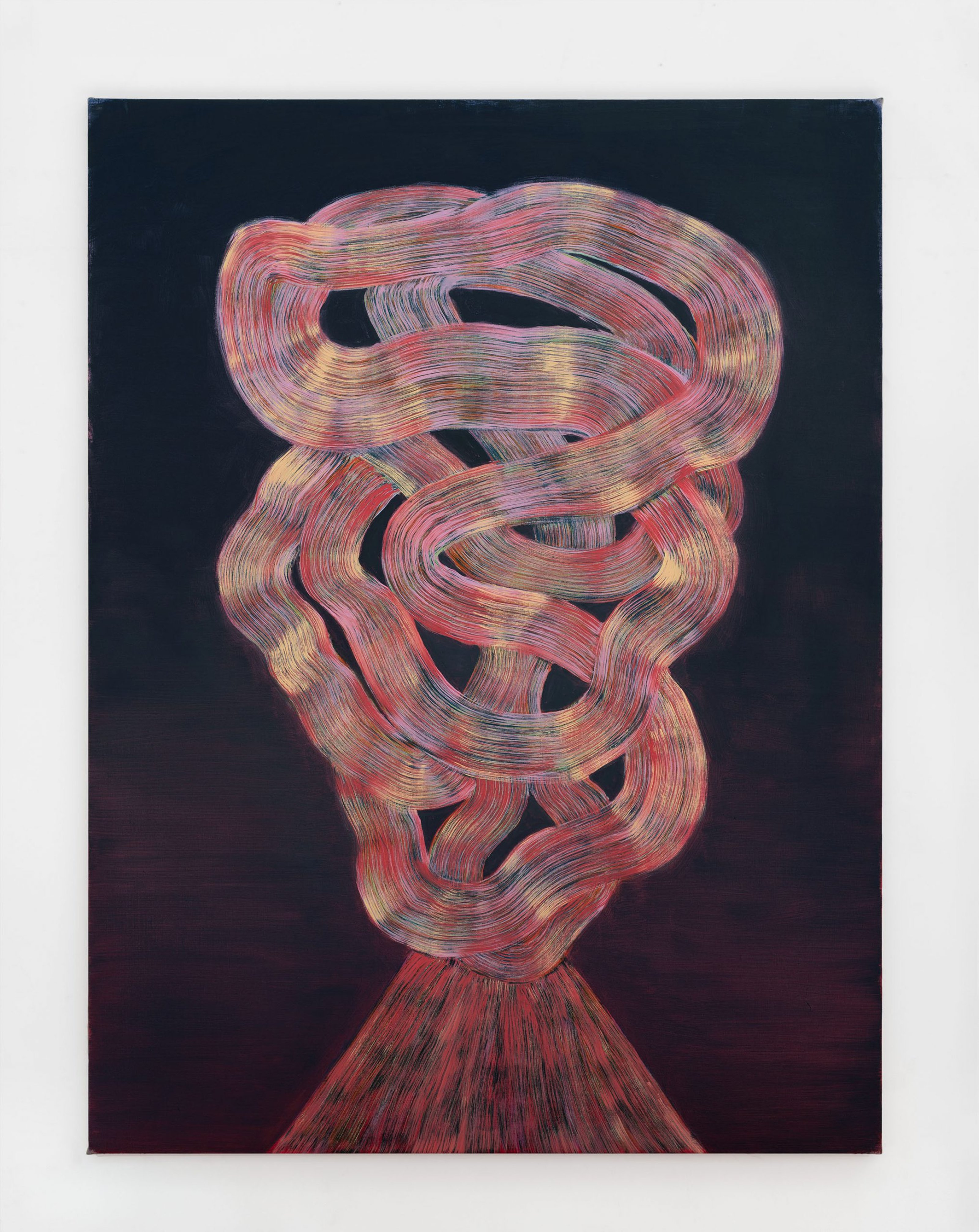

Robert Janitz / Mount Fuji, 2021 (oil, wax, flour on linen). Courtesy the artist.

C: You’re also painting on the floor, right? So the painting is on the floor and then with the canvas you’re on level zero. And then I guess you are building on from there?

RJ: And where is the elevator? [Laughs] The gradient was a big step in the way. And I resisted it for a long time, because I thought of it as a cheap thrill. You just do a gradient and then all of a sudden you have this exciting pictorial space instead of a monochrome background.

Robert Janitz / Purple Gin, 2021 (oil, wax, flour on linen). Courtesy the artist and Canada, New York

C: So that creates more movement within the image?

RJ: I guess what I call level zero is extremely factual. There is a monochrome background and then I smear some stuff on it. Call it painting. And then how do you give this whole thing dimensions? One way is maybe texture, another is a visual space like the gradient.

If you have a gradient and you put a line structure over it ,or just one line across the gradient, that line changes in color value in the way your eyes react to it. So then you have this exciting visual like you are on LSD all of the sudden.

Painting becomes time travel too, in a way. The painting surface is a membrane that goes between two spaces—a membrane between inner and outer world. As an anchor in space, there is no need for an observer or an audience. The idea of yourself disappears, it folds together. It’s like time and space travel.

C: Color is very cultural too. For instance, you find a lot of brighter colors when you go East, but in Europe the color can feel more muted.

RJ: Very, very much. I went to India specifically because they have a very different sense of color from my European idea. I think that was one of the biggest attractions of Mexico too, the colors. For my show in Istanbul, I based the wall colors on each of the three floors in the gallery on the colors that Barragán uses in Casa Gilardi.

I found in Mexico that the color black is a part of the living culture. Black is not considered death. Whereas in Germany, black would signify maybe a tomb or maybe that you are goth; this whole idea of “doomsday black.” In Mexico, black is a color of life somehow, and that changed the whole palette. The way they use colors is also certainly because they have so much light, an intense amount of light.

Robert Janitz / Mauna Loa, 2021 (oil, wax, flour on linen). Courtesy the artist and Canada, New York.

Imagine a plant in a room. In the same room in Germany, that plant wouldn’t make it. In Mexico, there is so much light coming in. I guess they found a different approach. My palette has clearly changed.

It’s odd how exotic something becomes, maybe at some point it becomes redundant as a word. Because I think exotic is from within the culture.

Robert Janitz / Galata Head 1, 2021 (ceramic tiles, pigment, glaze). Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

C: The word “exotic” does place the culture on the outside of the norm in a sense. Something that is a natural part of the culture becomes exotic through a Western lens.

RJ: This is of course colonialist. Super colonialist. There’s a Romanian poet, Gherasim Luca. He was a weird person, but he found this incredibly important idea that one learns how to stutter in their own mother tongue. You know, it’s just like you step out of yourself at this very deep level. And the closest thing to you to your heart is your mother tongue. Yet you speak it like a foreigner.

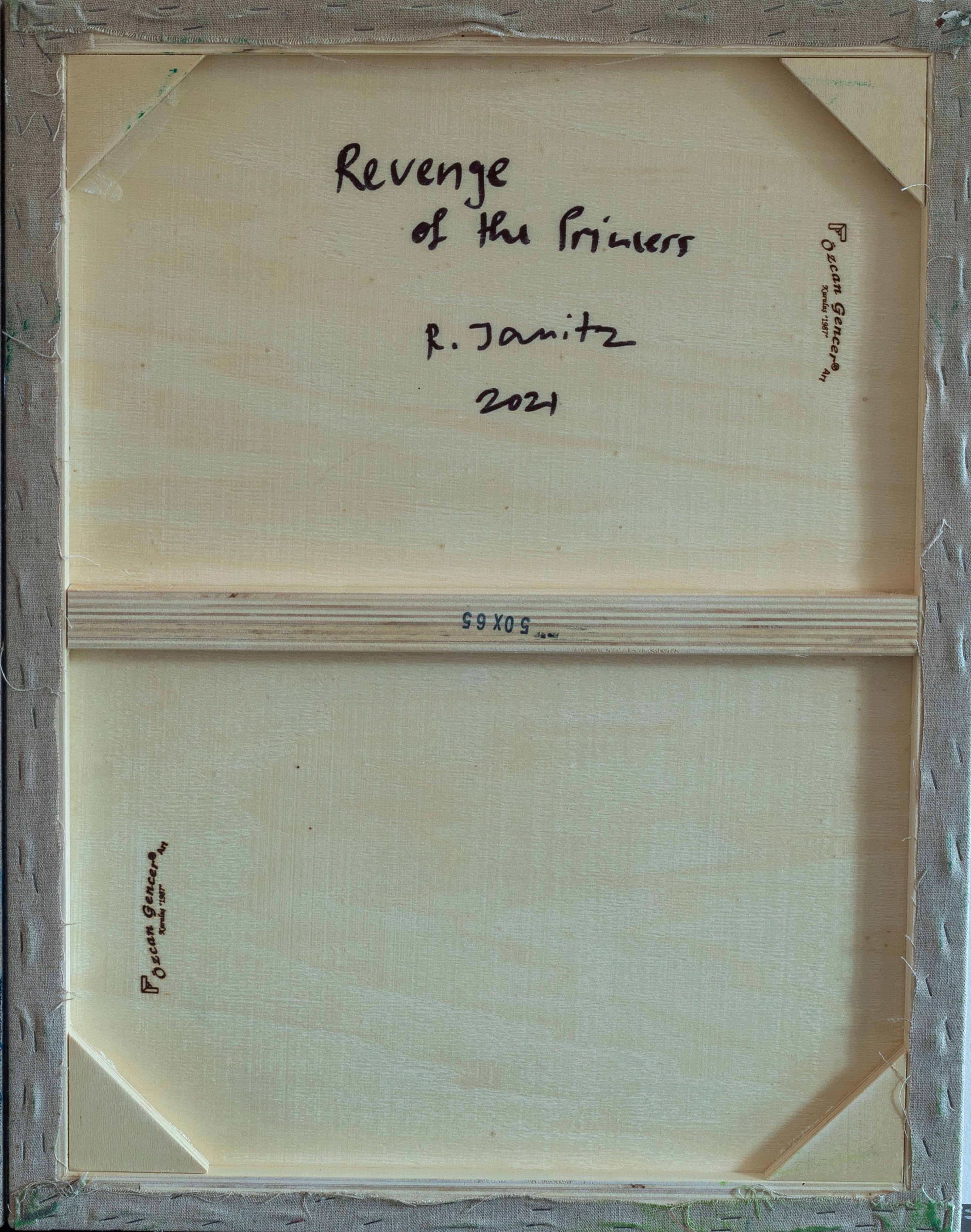

Back side of the painting: Robert Janitz / Revenge of the Princess, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Sevil Dolmaci Gallery, Istanbul.

End.