It’s tempting to apply the overused (and, some might argue, reductive) term of outsider art to the work of Randy S. Jones, but it probably makes more sense to describe this 78-year-old Decatur, Georgia, resident as an “insider artist,” in the most literal sense: For more than three decades, the retired lawyer has been diligently at work in the confines of his house on hundreds of boldly rendered abstract paintings that virtually no one has ever seen. Jones’s work is featured for the first time in the current issue of the nonprofit arts annual Esopus, and is also the subject of a related exhibition at _Esopus_’s pop-up gallery in Greenwich Village, which closes on June 2nd. This excerpt is from an interview in Esopus 25 conducted by photographer David Naugle, who first brought Jones’s work to the attention of Esopus editor Tod Lippy.

David Naugle: How and when did you become interested in art?

Randy S. Jones: Well, as a kid I liked to draw. As Picasso said, every child is an artist. And he’s right about that. But of course, we make sure we don’t channel our kids in that direction, because there’s no money in it. There were always law books lying around the house because my father was always reading them, so I decided to be a lawyer, and I graduated from the University of Georgia School of Law in 1965. I really didn’t do any art at all until 1970, when I settled in Decatur, age 30, and started practicing law. Around that time, I started going to a drawing class in the evening—just three or four other people, in somebody’s basement. And then the drawing led me to oil paintings. After 10 years as a lawyer, which was not very fulfilling for me, I called it quits and I went to Philadelphia, where I studied art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts for nine months. And I came back and have been doing art since 1981 or so.

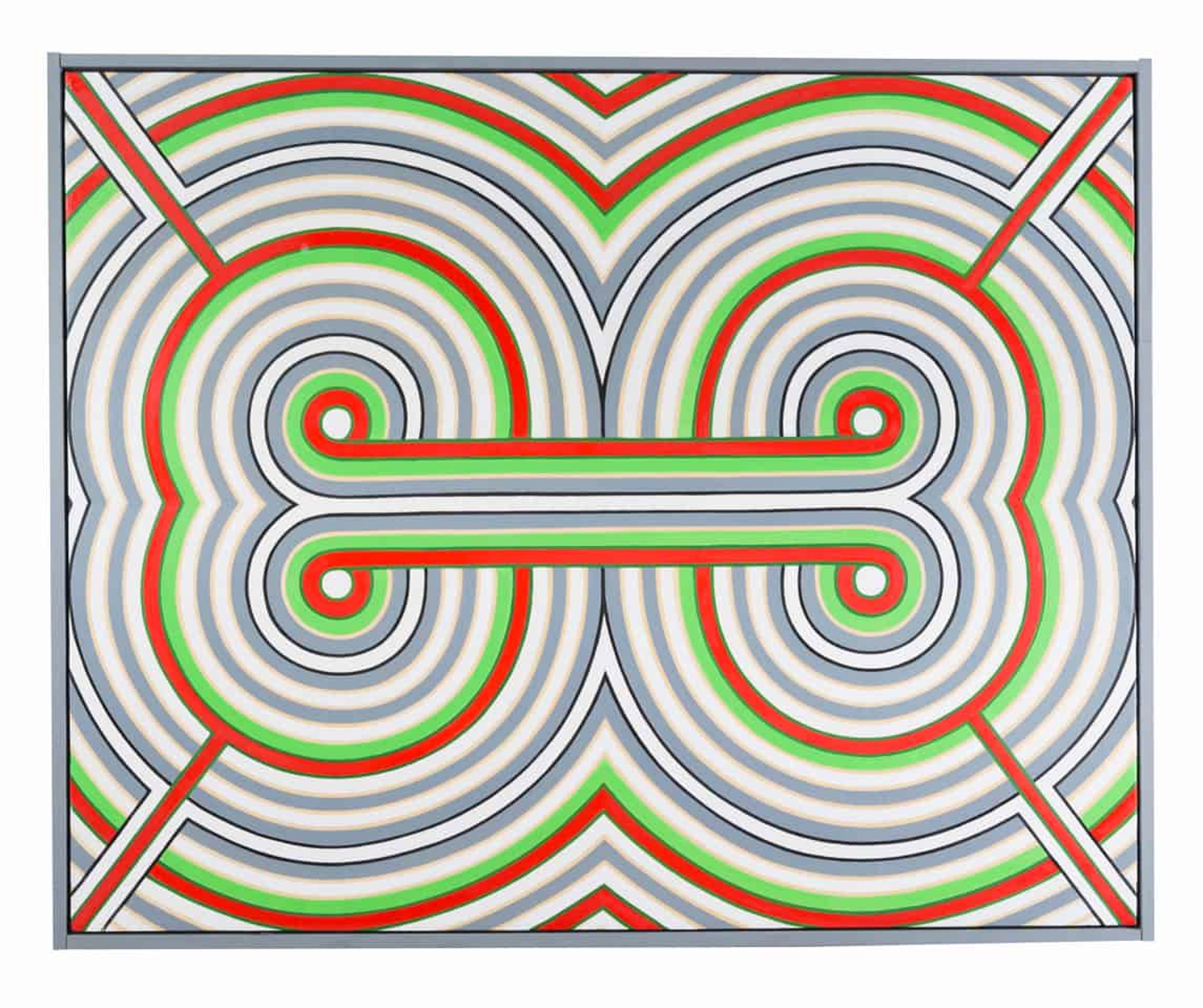

Randy S. Jones Two by Four #01, 2014 (adhesive duct tape, handmade wood frame) – © David Naugle

DN: What was your experience like as a student there?

RSJ: It’s an academic school—you learn to paint academically, representationally. We used live models, and that’s all we did for 10, 12 hours a day for nine months: We just painted nude models. And after that, I came home and continued to paint representationally, oh, for quite a while. I moved into abstraction in the 1990s. I cannot definitely pinpoint what caused me to do that; I guess it was just the desire to find new forms of expression. But it was a gradual process, and then eventually that was the only kind of artwork I did, even today.

DN: What is the appeal of abstraction for you?

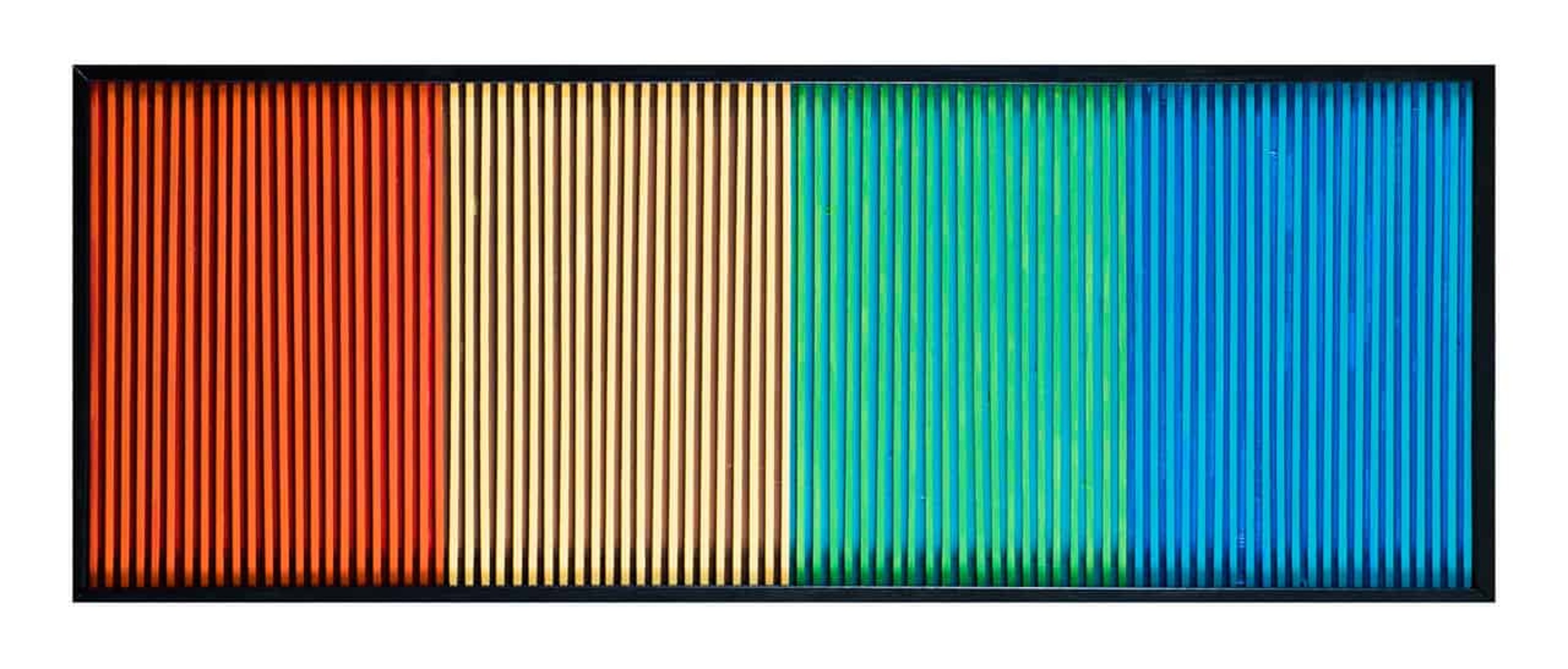

RSJ: Well, that’s a hard question to answer. You’re looking for a way to express inner feelings, and you don’t know what it is that causes you to move in one direction or the other. With abstraction, of course, you’re not confined to representing something that you see in front of you. The beauty of it is that you can take color—which involves more emotion than any other aspect of art—and you can manipulate and exploit it to the fullest degree, which you cannot do in representational art. I just happened to have some things around the house—duct tape, wood scraps, and some other materials I had scavenged from dumpsters—that I began to incorporate into the pictures. And also, I didn’t have to buy canvases. [laughs] That was important.

Art is a process. When you start doing a picture, you don’t know how it’s gonna end up. Because one mark, one expression, may lead to another avenue. That’s the reason I like abstraction, because it gives you so much freedom. There are no limits.

DN: It sounds like you don’t spend much money on materials.

RSJ: I was just picking up things on the sidewalk or whatever people were throwing out. You’d be surprised what they throw out. Anything can be used as artwork. I don’t think I’ve ever bought anything for the house. My sofa, my bed—everything came off the curb. My brother always said, “Well, it’s gonna go back where it came from.” Which is probably true.

DN: Can you talk about some of the artists who have influenced you?

RSJ: I wish I could, but because of old age they don’t come to mind. Having gone to the Academy, of course, I was very much influenced by representational art and people who paint academically. It was the oldest art school in the United States, you know. I used to could resurrect all of those names and throw them out at you, but to some degree now I’ve forgotten.

When I came back to Georgia after being in Philadelphia, I started being exposed to other influences. After I bought this house, I had a tenant upstairs for a while, Edmund Pollastrello, who was a wonderful abstract artist and sculptor. He now lives in Grand Rapids—he got married and had to make a living, so that was the end of that. But I was fortunate enough to be around people like him who appreciated art very much.

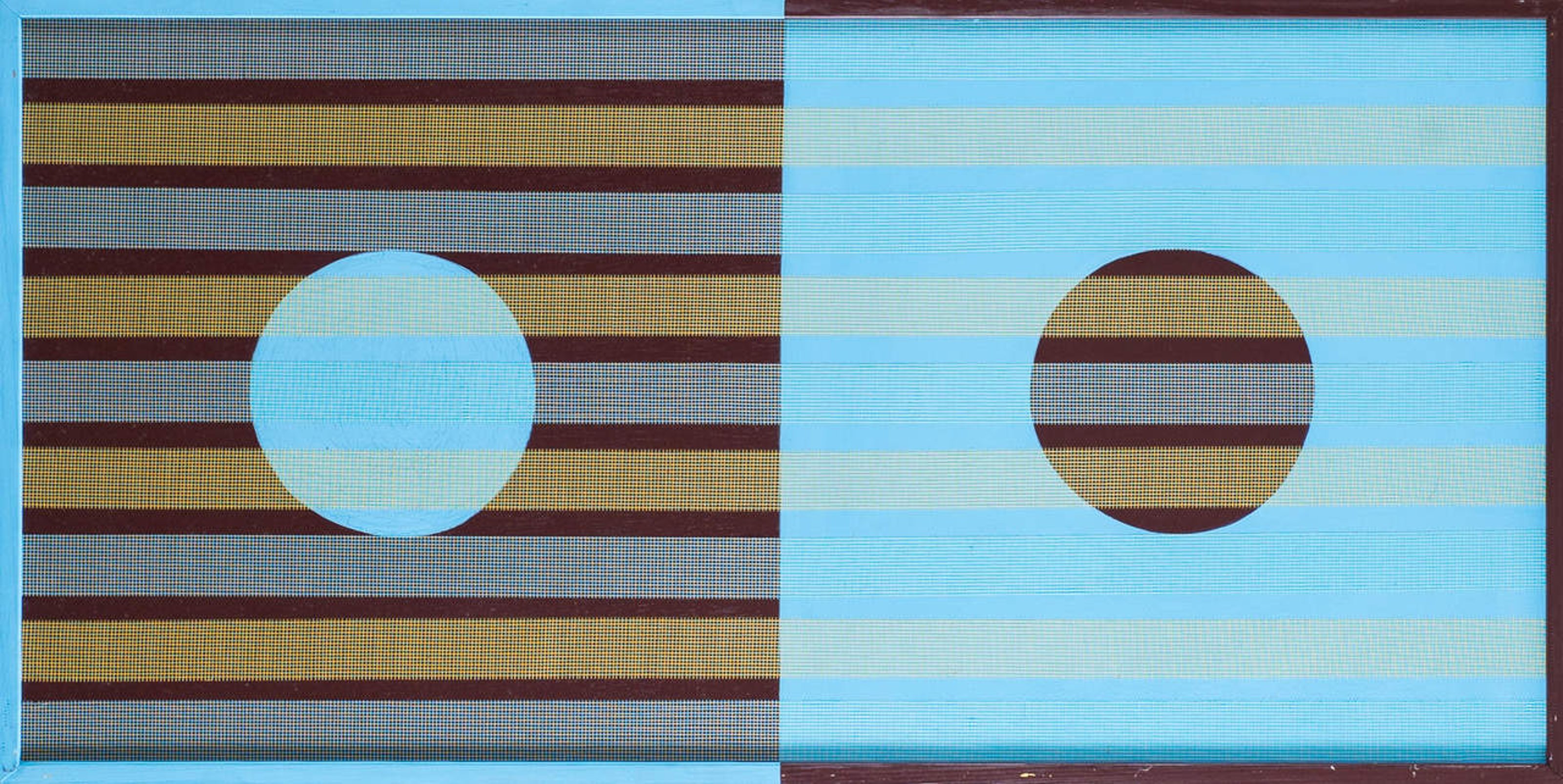

Randy S. Jones Anomaly, 2014 (oil on canvas, handmade wood frame) – © David Naugle

DN: You mentioned your tenant’s sacrificing his art career to have a family. Was that a decision you ever considered making?

RSJ: I also gave up marriage and family life, obviously. Never got close to it, really. I live in a good community that’s very family-oriented, so it’s been kind of tough being accepted in the neighborhood, because I’m the only person who doesn’t have kids. Only a few people know that I’m an artist—hardly anybody in the whole neighborhood—because they just don’t stop by like they used to in the old days. When I moved to Decatur, in 1971—of course, I was much younger—there was no central air, so people’s doors were open in the evening. And I could knock on every door, and they’d say, “Well, come on in, Randy, sit down.” But now I wouldn’t dare knock on anybody’s door, under any circumstances. Five o’clock, that door is closed, just like the Bastille—you couldn’t get into it if you had to. And so I have no communication with anybody. I’ve often proposed to the city council that we designate a day in every season in which we draw names in the community, and whichever name you get, you go to their house for, you know, coffee or whatever, and then you invite them to your house. Which I think would improve the community. It’ll never happen, of course.

DN: Didn’t you tell me you’d painted some portraits of some of your neighbors a while back?

RSJ: Many years ago, I did paint portraits of some of the young kids in the neighborhood—about six of them, I think. And only one of my neighbors accepted the portrait. The rest of them didn’t want them. I still have them. So there was not much encouragement. Although when I got back from the Academy and was still painting academically, they wanted to commission a portrait of a retired judge in Dekalb County. I had done a self-portrait, which I submitted, and they were impressed by it—maybe my being a lawyer helped me out, I don’t know. Anyhow, I was commissioned to do the portrait, which still hangs in the Dekalb County Courthouse. That was the only time I ever received money for my artwork.

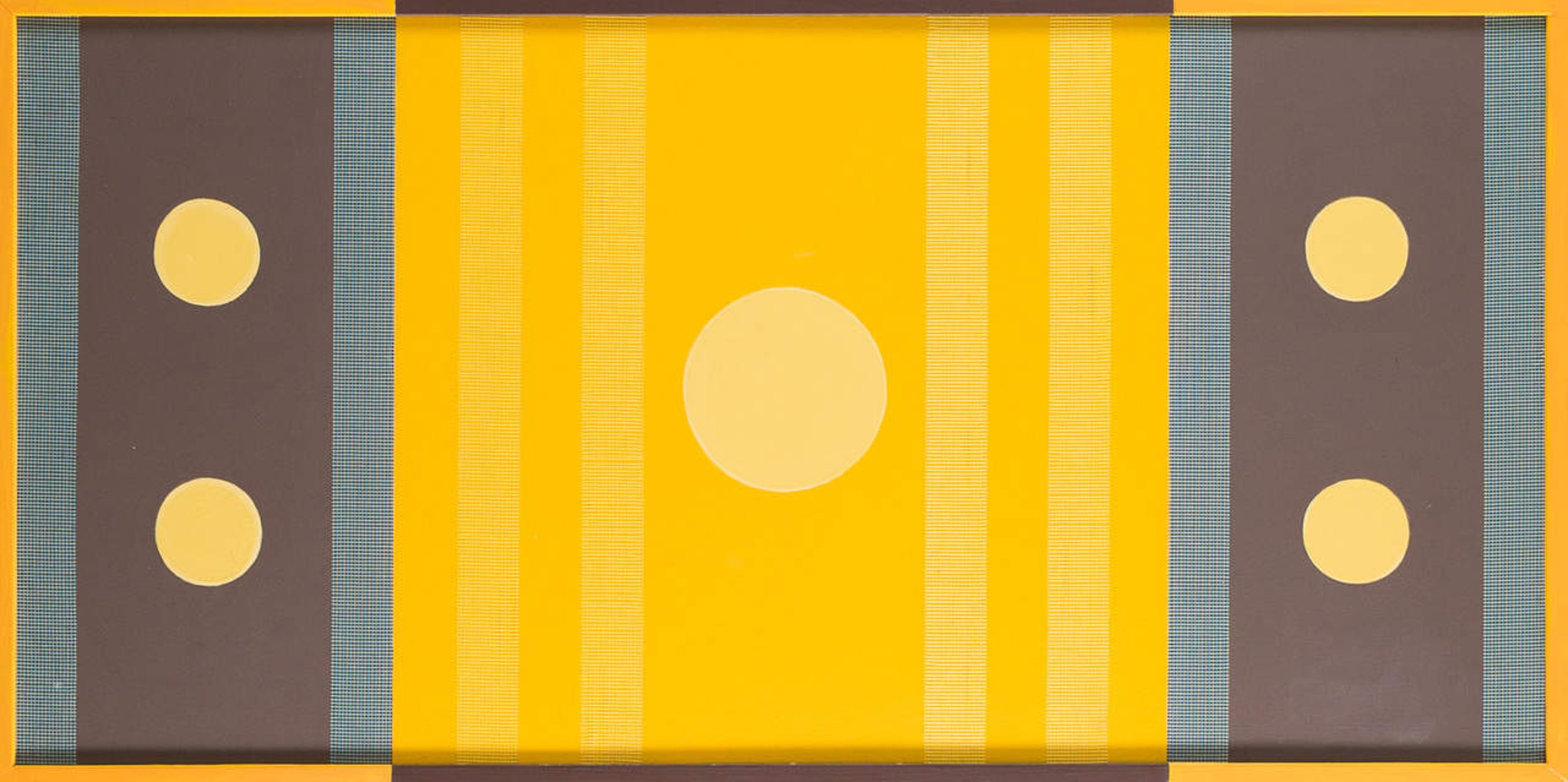

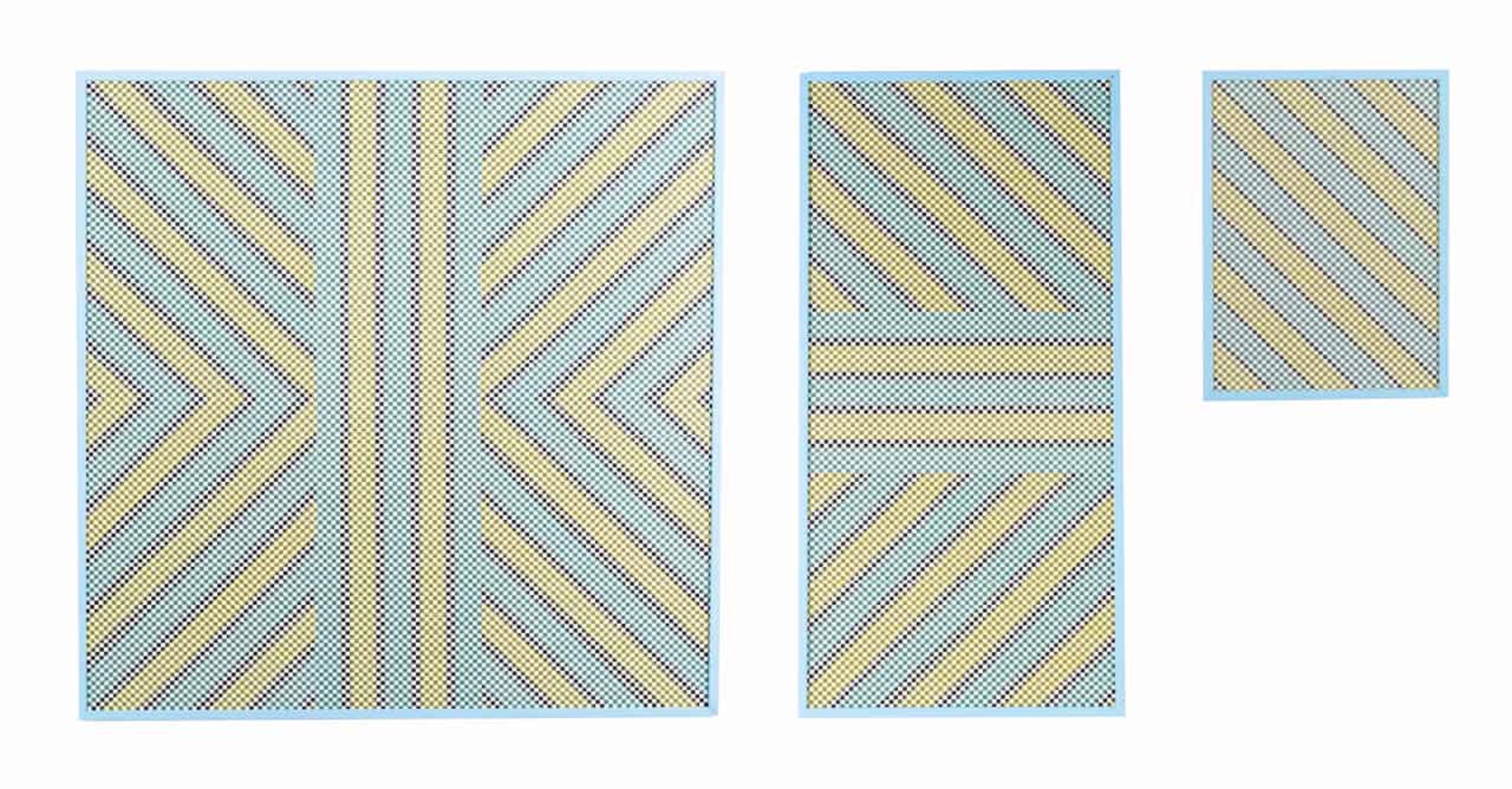

Randy S. Jones Triptych, 2015 (adhesive duct tape, drywall tape, handmade wood frame) – © David Naugle

DN: So, obviously you don’t measure your success by sales…

RSJ: Obviously not. I’d be a real flunky if I did. [laughs] The only money I made off of art was that portrait, which I think was $1,000.

DN: Have you ever had your work exhibited?

RSJ: My exhibition history is pretty nonexistent. Recently, the public library in Decatur allowed me to exhibit several pieces. Over a period of weeks I showed about four or five paintings in the library in the hallway, which I appreciated. They were representational paintings as well as abstracts, and I got a lot of comments. But I’ve never had a show at a gallery, because I think in exhibiting abstraction, you need to stand at least 20 feet away from an artwork, and most galleries—at least I don’t know of any here—aren’t large enough to exhibit large abstract pictures.

DN: How many artworks do you think you’ve made?

RSJ: I’m not sure exactly how many pieces of art I have in my house—I’ve never taken an inventory. [laughs] I would like to do that one of these days. I would have to speculate that it would be around 200, maybe more. Those are the ones I can think of, but I’m sure there are a lot out there I’ve forgotten about. I never dreamed I would come up with a house full of art.

DN: What role do you think art can play in society?

RSJ: We live in a very commercial world, but if we focused more on the arts—not just fine arts, but performing arts and all the other arts—then I think we would have a much more peaceful world.

Of course, in our schools it’s just a sideline sort of a thing; it’s not a part of the important curriculum, at least in the schools that I’m familiar with. But it should be. It’s just a part of us. It’s everywhere. It’s in your machinery, it’s in the design of cars, books—everything is really about art.