Let’s begin with a simple fact: very few monuments to the Non-Aligned Movement exist in the world, even though the movement has been active since the early 1960s and today includes over a hundred and twenty member states. Why is that so?

In order to understand this fact and to make some kind of assumption, we should look back into history to the beginnings of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Between 1 and 6 September 1961, the representatives (all men, with the exception of Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike of Sri Lanka) from twenty-five politically diverse states gathered in Belgrade. It was a grand event, a meeting of mostly former colonies from the Global South and Yugoslavia. The conference was also an attempt to create an alternative transnational political alliance, a third way between the two blocs, aiming to change the existing global structures and to create a more just, equal and peaceful world order. The movement very early on declared itself anti-imperialist, anti-colonial and anti-racist, following principles such as peaceful co-existence, respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, non-interference in domestic affairs, equality and mutual benefit. Kwame Nkrumah, president of Ghana, pointed out what seemed like the movement’s essence: ‘We face neither East nor West; we face forward.’1

After the initial years, the NAM transformed itself from being distinctly political to a movement with a strong economic and cultural agenda. With regard to the latter, it was mainly concerned with cultural imperialism, restitution and cultural exchanges. Interpreted from today’s point of view, this quest also envisioned rewriting historical narratives; the emphasis was on altering epistemic colonialism and cultural dependency. Consequently, art and culture were primarily about politics and history, and an attempt to pluralise the experiences of modernity in the non-Western parts of the world. It seems the movement was aware of the fact that only this way it could enter the world’s (cultural) space on an equal footing. The motto was to make the Global South a place from which to speak. The Havana declaration further highlighted:

(…) the exchange and enrichment of national cultures for the benefit of over-all social development and progress, for full national emancipation and independence, for greater understanding among the peoples and for peace in the world.2

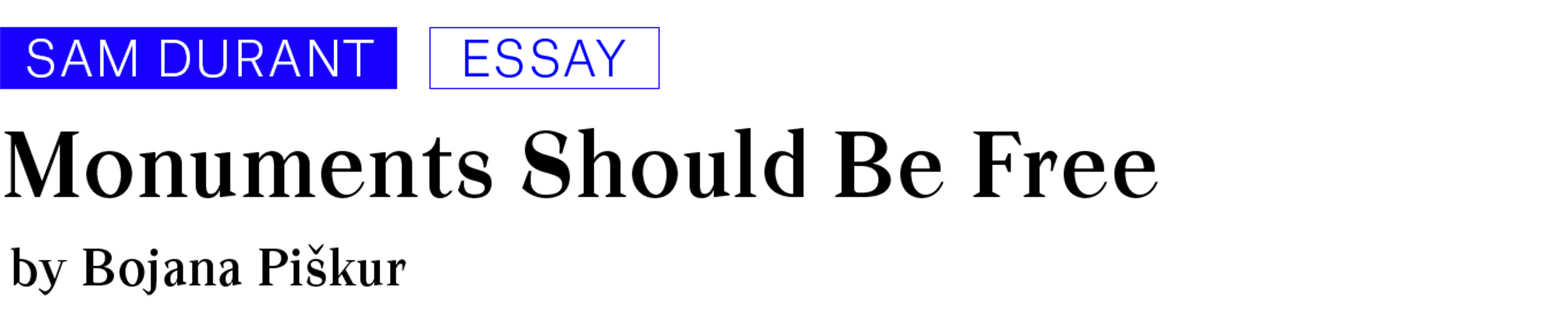

Scramble for Africa, 2020. Coloured pencil on paper, 118,4 x 150,5 cm. (c) Sam Durant. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

These networks pretty much lost their significance in the late 1980s, when global geopolitics changed drastically. Quite a few authors, though, Samir Amin3 among them, have looked back to the NAM as a possible way of ‘de-linking’ from current globalisation, of finding another way which, as he emphasised, did not mean reverting to the old pre-colonial or colonial state, but bringing new patterns of modernity to the Global South. (The question is: what kind of modernity?)

As mentioned, in spite of the NAM’s historical relevance on the world political stage, there have been, surprisingly, very few monuments to remind us of the movement. Let’s look at some of the examples.

Image: Proposal for Non-Aligned Monuments, Free Movement 2020 (c) Sam Durant. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

In 1961, Belgrade urbanists and architects were faced with the difficult task of making the city more attractive to the foreign guests from all over the world on the occasion of the first NAM conference. Among the numerous proposals, there were a couple of outstanding plans. One of them was the idea for the establishment of the Friendship Park in New Belgrade, at the confluence of the Danube and Sava rivers. The park would have a ceremonial and representative character and would represent ‘a symbol of the struggle for peace and equality for all peoples in the world.’ It was officially opened on 7 September 1961 with a tree-planting ceremony of the participants in the conference. Twenty-six plane trees were planted along the prominent, hundred-and-eighty-metres-long Peace Avenue; next to each tree a stone plaque with the name of the statesman, the country of origin and the year of planting was placed. What is interesting, though, is that the species of plane tree chosen for the park was Platanus acerifolia, which is actually a hybrid of Platanus orientalis (oriental plane) and Platanus occidentalis (American sycamore). Perhaps this particular tree was selected on purpose: to symbolically emphasise that non-alignment existed not only in politics, but also in nature. However, the Belgrade Park is not the only Friendship Park in the world: another one exists in Indonesia. It was inaugurated by President Suharto on 1 September 1992 to commemorate the tenth Non-Aligned Movement’s summit. Hundred and eight ‘friendship trees’ were planted in this park, trees that are native to the country of each participant in the NAM conference.

Image: Monument “Eternal Flame” located on the Avenue of Peace, Belgrade. Image credit: Panoramio, user Mister No

However, besides planting trees and designing parks, there have also been a few other sculptural monuments dedicated to the NAM. In Belgrade, in 1961, they put up four temporary monuments at various locations in the city. They were all removed after the conference, with the exception of a quite unusual twenty-seven-metres-high obelisk, which in the following decades was left to decay and fade into oblivion. Another obelisk was located in the former Marx and Engels Square and was made of steel pipes and neon. The emblem of the conference stood at the entrance to the city, and in the Dedinje neighbourhood an abstract geometrical object was placed representing peace, equality and international co-operation, the principles of non-alignment.

Proposal for Non-Aligned Monuments, Free Movement, 2020. Wood, foam rubber, acrylic variable dimensions, approximately 132 m², 10 objects in all. (c) Sam Durant. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Whereas the Belgrade monuments were temporary and quite abstract, that was actually not the case in Jakarta and Georgetown, Guyana. The Non-Aligned Monument in Georgetown was erected in 1972 to honour the four founders of the movement, as well as the NAM conference held there that year. The busts of Nasser, Nehru, Nkrumah and Tito are characterised by a realistic, figurative style. The Non-Aligned Countries Friendship Monument (1992) in Jakarta is a rather strange, postmodern, globe-shaped monument, supported by a fountain with five pigeons in the centre, symbolising ‘togetherness, peace and spirit.’

It seems that monuments haven’t really worked out favourably for the Non-Aligned Movement. The movement was to stimulate different kinds of modernities and progressive ideas, in arts as well, but the remaining monuments can’t be said to embody this vision. They were obsolete already at the time they were erected, with the exception of the abstract, temporary public sculptures in Belgrade. But what are monuments, actually? They require heroes, historical figures or important events often related to national politics. Monuments can also be destroyed in the course of time, or their symbolic value may shift due to political changes. Monuments have an aesthetic and political side to them and are often open to various interpretations that are different from the ones originally intended. Some monuments simply continue their life without being considered monuments any longer. They lose their monument-ness. Robert Musil was aware of this fact when he wrote: ‘There is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument.’

Trope, 2020. Two-channel video projection with sound, 12:35, looped. (c) Sam Durant. Courtesy Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

However, returning to the NAM: does that mean the movement did not have any heroic figures to commemorate, exceptional events to glorify? Or was it that the NAM was ahead of its time, going not only beyond the two blocs division, but also beyond the human – non-human ontological relation, reminding us of ‘the finitude of humanity, of a future without us’? Only time, and, perhaps, the magnificent plane trees in Belgrade, have the answer to that question.

Image left: Another World is Possible, 2020. Lightbox with vinyl text, 193 x 241 x 20 cm. (c) Sam Durant. Courtesy Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

Visit Sam Durant: Proposal for Non-Aligned Monuments, Free Movement on Collecteurs

About the Author

Bojana Piškur, Ph.D., is a writer and curator at the Museum of Modern Art in Ljubljana (also known as the Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova). Her work focuses on political issues as they relate to, or are manifested in, the field of art, with an emphasis on the regions of former Yugoslavia and Latin America. A graduate of the Department of Art History at the University of Ljubljana, Piškur received her Ph.D. at the Institute for Art History at the Charles University in Prague, the Czech Republic. In the past, her writings and lectures have focused on topics such as post avant-gardes in Yugoslavia, experimental film, racial education, socialist cultural politics, and the Non-Aligned Movement, always within the context of the wider social and political environment.