May 28, 1871: The Paris Commune

On 28 May 1871, the Paris commune, the world’s first modern working-class socialist uprising, was crushed when the government massacred thousands of working-class men, women, and children to regain control of the city.

After the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, the French government sent troops to Paris to reclaim the national guard cannons. But on 18 March the residents of Paris refused to give them up, and the national guard mutinied. The working class and the mutineers seized the city and set about re-organising a society based on a federation of free, independent communes run by councils with elected and instantly recallable members.

Workplaces were turned into cooperatives, and the Louvre museum was converted into a weapons factory run by its workers.

In April, rebel commune national guard troops of the 137th battalion seized the local guillotine, smashed it to pieces and burned it outside the town hall of the 11th district to the applause of a huge crowd of onlookers. The district commune committee had voted to seize these “servile instruments of monarchist domination” and destroy them “once and forever… for the purification of the district and the consecration of our new freedom”.

image: The rue de Rivoli after the fights and the fires of the Paris Commune, 1871. Photograph: Niday Picture Library/Alamy

On 21 May, government troops attacked the city, beginning a so-called “bloody week.” On 27 May, its penultimate day, around 150 communards who had holed themselves up in the Pere Lachaise cemetery were overrun, then lined up and shot against the cemetery wall, which is known today as the communards’ wall.

In total, around 30,000 people were massacred as the government and armed capitalists enacted their bloody revenge, killing and maiming at will. Many were murdered after they surrendered, and their corpses dumped in mass graves.

Despite the violent repression, the spirit of the commune lived on, and the slogan “Vive la commune!” (“Long live the commune!”) is continually daubed on Paris walls, most notably during the May uprising of 1968.

May 1871: The statue of Napoleon I was pulled down along with the Vendome Column on which it stood in a ceremony during the reign of the Paris Commune. Bearded painter Gustave Courbet is ninth from the right. (Photograph by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

May 28, 1913: Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) Strike in Philadelphia

On 28 May 1913, dockworkers in Philadelphia won a landmark strike which had begun exactly two weeks prior.

Philadelphia dockers were a highly diverse workforce, of whom 52% were Black, 39% Polish or Lithuanian and 9% Italian or Irish.

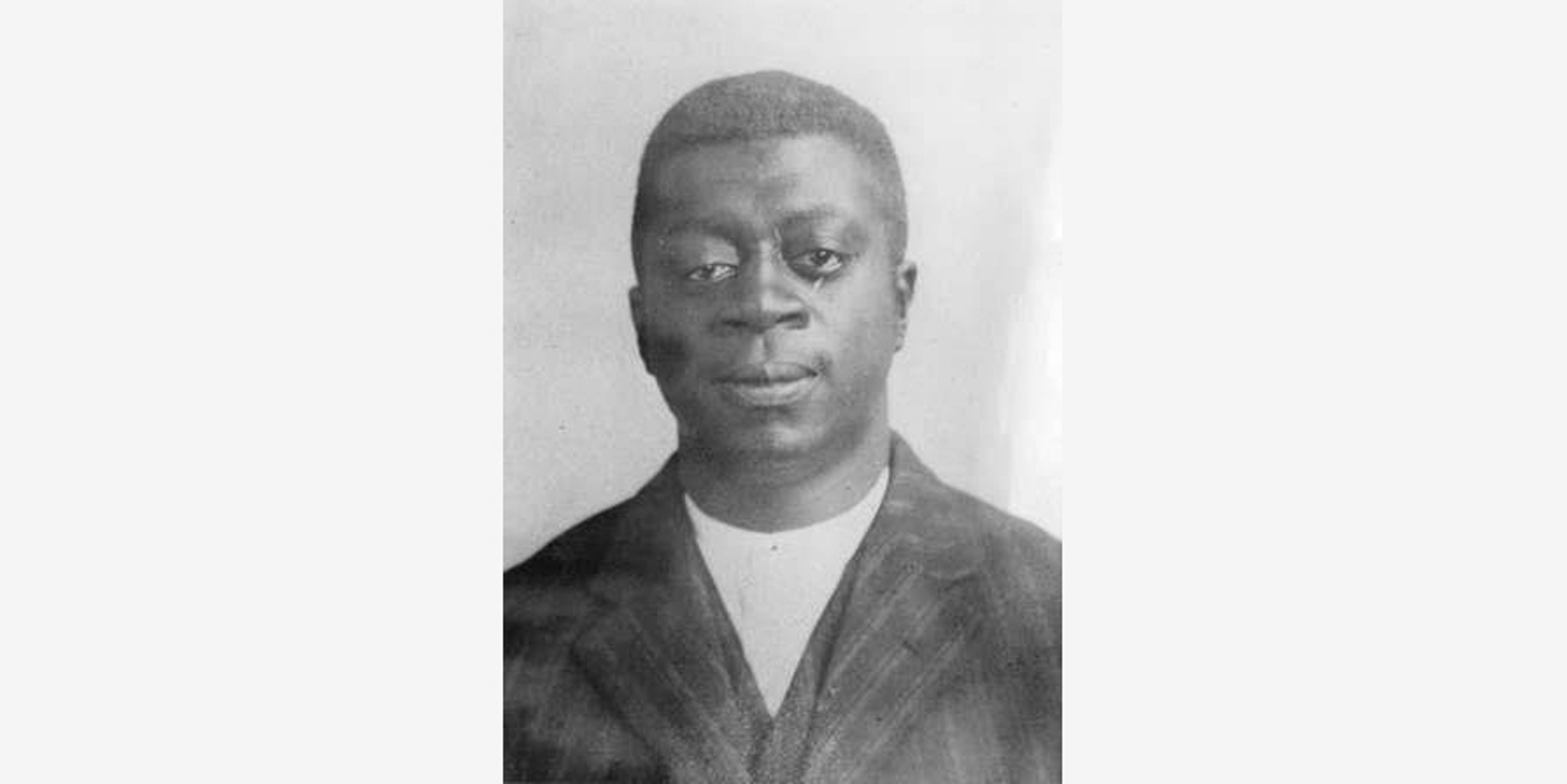

An African-American docker and activist in the Industrial Workers of the World union (IWW, often known as the “Wobblies”), Ben Fletcher, was a key organiser.

Ben Fletcher, leader of Local 8, IWW.

On 14 May 1913, 1500 workers walked out on strike demanding an hourly wage of $0.35 for everyone, a maximum 10-hour working day, additional pay for work at nights and on Sundays and public holidays, and for union recognition and collective bargaining.

The dispute held up 100 ships, and the workers made all their decisions collectively in mass assemblies, with a strike committee made up of at least one representative from every nationality of a worker to ensure that discussion could take place in every language.

Employers tried to break the strike by rerouting ships, hiring strikebreakers and private detectives from the Pinkerton agency. There were some pitched battles between strikers and their supporters, including many women, on one side, and police and strikebreakers on the other.

But the workers held firm, and while their basic pay remained the same, they achieved all of their other demands.

After the dispute, the workers officially formed Local 8 of the IWW. Contrary to most unions at the time which were segregated and only admitted white men, the IWW aimed to unite all workers into one big union. Local 8 had more African Americans than any other Wobbly branch and was ably led by Fletcher.

Local 8 was probably the most racially and ethnically integrated union in the United States during the WWI era.

It was also among the most durable branches of the IWW, dominating the waterfront, despite massive employer and government repression, for almost a decade.

End.

image: IWW sticker, 1910s

This article is part of a series of special features for the exhibition ‘1-31’ curated by Adam Carr.