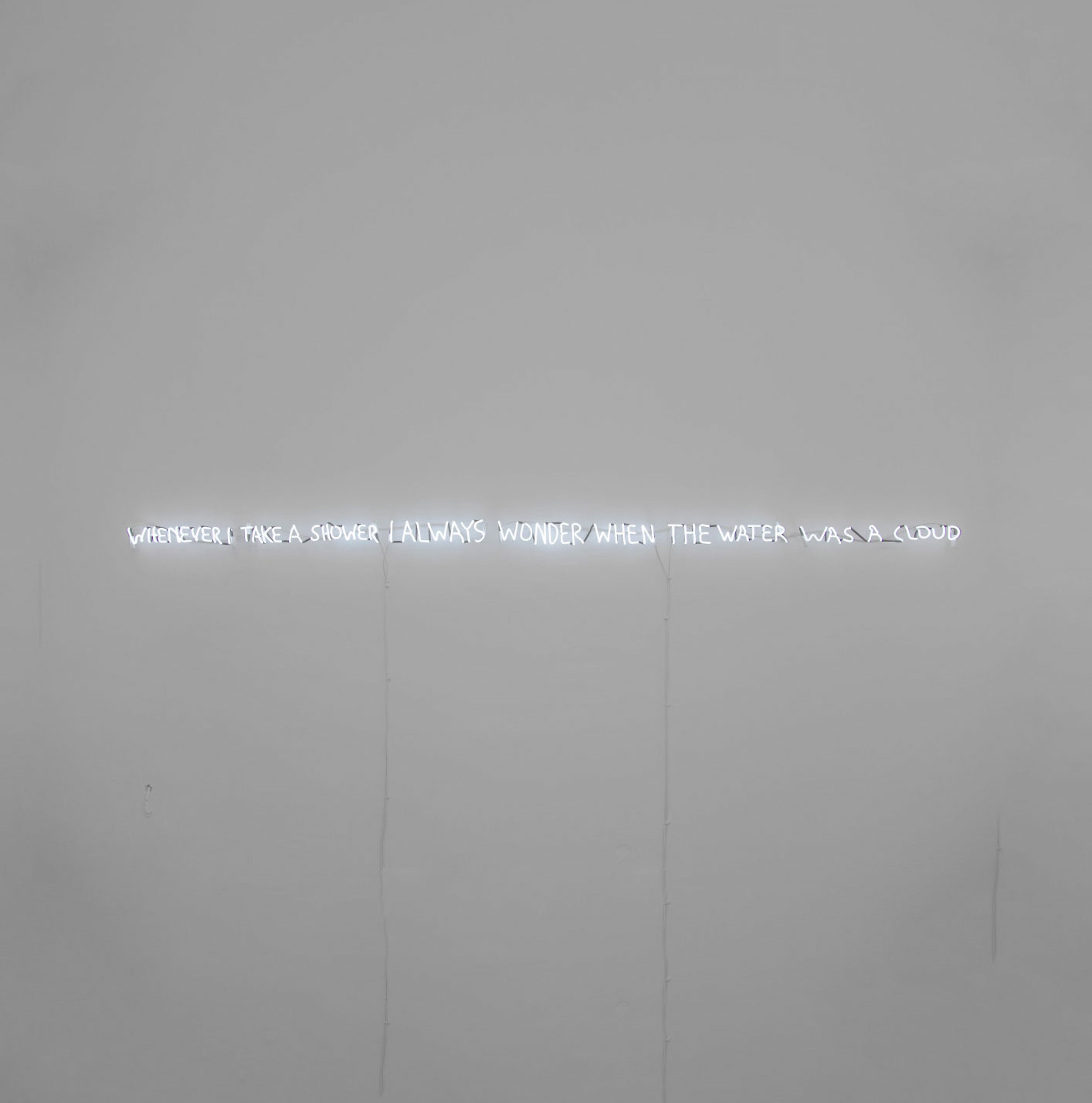

David Horvitz / Untitled, 2000. Courtesy Kerenidis Pepe Collection.

Àngels Miralda: Hello David, firstly, I wanted to ask you about the two elements of time and the sea that are very often the subject of your work. How has growing up in Los Angeles in proximity to the Pacific affected your view of both entities?

David Horvitz: There are many ways to respond to this. One is about a deep affection, a love for the ocean. One is about the idea of home. I remember sitting in a Hawaiian restaurant with my mom in one of LA’s suburban beach cities, and the owner looked at us and said, “we are water people.” I’ll never forget that! But another, which is somewhat related to the idea of home, but I think more broadly as this idea of site or of a setting. A setting where work is made. I always think about some of the early California conceptualists, and how the place of California seemed to have an important role as subject matter in many of these works. But I also thought, in a post-studio practice, you make work where you live. There are so many works I made on the Palos Verdes Peninsula in my early years as a very young artist. The peninsula is the southern end of the Santa Monica bay, the bay that is basically most of the beaches that people understand as LA beaches. It juts out into the sea, and still (though it’s constantly decreasing) has some wild areas.

DH: There is a history of Japanese farmers and abalone fishermen, and the indigenous populations. It could be seen as this kind of remote romantic California landscape. It was a place I would drive to and inadvertently a site for making work. Videos, photos, writings, etc… It was the place where works were being made, but also the subjects. But to really answer your question, growing up on the coast you have this relationship with a place that has an end. It is where land just ends. Where you cannot go any further and can only just stare out into the horizon. It’s a relationship with distance and the unreachable. Unlike the desert, to the east, where you can be surrounded by the vastness (which is actually maybe a derogatory stance against the desert, since in fact the desert is so full), on the coast you are at the edge of it.

For time, time is always intertwined with space, it is how we experience place. And so what is the time of the coast? Of the tides? Of the waters? You have the time of leisure and the typical LA beach afternoon doing nothing (which sadly I don’t see my friends engaged with as much as I think they should, partly because everyone is “too busy” these days), but you also have the time of the tides, connected to lunar rhythms, earth spinnings, wave crashings. Other rhythms that could exist in contrast to standardized clock time.

David Horvitz / Yesterday (monthly subscription), 2018. Courtesy Kerenidis Pepe Collection.

ÀM: Your work “somewhere in between the jurisdiction of time” is included in Collecteurs’ online exhibition The Wave. This work pays attention to the significance of geography and place. How does this work change when you exhibit the documentation online?

DH: I think the key word here in your question is “documentation.” The question is: is this the work or the documentation of the work? Is the documentation of the work the work? What exactly is the work? For me the work was to displace the timeline. So it has to exist in physical space. But the work can also exist in one’s imagination. Or maybe as a parable or an allegory of some sorts. Or even as hearsay. Putting something online, I’m not sure what it means, but I like this notion of something that is out of your control, that can circulate on its own terms, like a rumor.

ÀM: Another work “In the limit of disorientation” is currently being shown in Istanbul. The senselessness of thinking water as territory is employed in a different region creating an entirely different piece. How was it for you to work with this concept across different areas?

DH: Originally the curators wanted the aforementioned work, the timeline piece. But it wasn’t feasible to bring the California time zone to Turkey. I had thought to redo the work, but to do a different time line. Like a river between Turkey and Armenia, or part of the sea between Georgia and Turkey. Or somewhere in the water west of Greece, where the time zone changes. But that didn’t end up working out. Instead, I made a new work, that wasn’t a line at all, it was more of an area, and so the work is displayed differently. Again in open glass containers, all unique and blown in Istanbul, they contain water from the western most point of what is considered the Asian continent, which happened to be where I was having a residency with Garp Sessions. The residency and the exhibition are unrelated. And just through coincidence (or maybe kismet) the work took on this new idea and shape.

ÀM: In your work there is a lot of humor. At least it gives us the feeling of a double-take. In 2015 you published the book “Mood Disorder” which follows the online trajectory of a self-portrait. I couldn’t help thinking about the relationship we saw between waves and emotions - can you speak a bit more about this image?

DH: This work is funny. Everyone always laughs when I present it. But it’s also not funny, it’s about depression. But also humor and depression are sometimes intertwined. The image is a photograph my friend made of me in the early morning light on the beach in New York. I had my head in my hands and wanted to make a cliche image of sadness. I had collected stock photographs of depression. Which turned into an artist book called Sad, Depressed, People. This book was basically the visual research that would turn into Mood Disorder. I was interested in what a stock image of depression looked like. How depression or sadness is performed by the model, how it is communicated, its pose. Obviously this is not what depression looks like. Depression just looks normal. It’s the person who is smiling and says they are feeling great. But they aren’t. On a side note, there was actually a petition by a British comedian asking people to stop using the “headclutcher” image as a way of representing depression.

So back to my fascination with these images… One of the reasons was that a lot of times stock images are used for advertising. And in the advertising image the norm is to present someone who is in a state of something you desire. Someone who is happy because they are drinking a soda. Someone whose life is great because they have wealth and things. Someone who is so excited on their cruise in Hawaii where they can eat sushi everyday from overfished oceans. There is a kind of distance here: you are not this image, but this image could be you. This is classic photo advertising thinking. Obviously the images of sadness are not all used for advertising…

“stock image” made by David Horvitz. Courtesy the artist.

DH: Maybe they are used for magazine articles about depression. Maybe they are used for product packaging (for painkillers?). But what I was interested in was this idea that this image wasn’t presenting a desired state. Instead, depending on the context of how it is used, it may show something that you identify with. Maybe it is an advertisement for suicide prevention or domestic violence presentation or therapy for depression, it shows you. You see yourself. So I made this image. And it was put onto Wikipedia. And Wikipedia is copyright free. You can use images and texts without having to pay royalties, like you would using images from paid for stock image database sites. And let's say you are not like me, whose images in the Sad, Depressed, People were all used without permission, excising my artistic fair use. Let's say you are a small newspaper and you need to have the rights to the images you are going to use so you don’t get sued. You can go to Wikipedia and basically use those images as free stock images. So someone looks up Mood Disorder and sees that image and they use that for their site. And so my work was this image in circulation online. I used Google’s reverse image search to locate where the image had “traveled” to.

ÀM: This leads us to the topic of circulation. Online images circulate like currents and information. Your book “How to Shoplift Books” offers practical as well as humorous ideas about how to steal from bookstores. Is this a practice of resistance?

DH: I want to answer this question honestly with consideration. My initial response would be to say no. Only because this book is kind of a joke. If you read through it, it is a joke. Though, yes, there are things you can use in it to steal a book. Like, you can put the book inside an envelope and seal it and no one can open it because that is a federal crime. At least in America. But, I would hope someone doesn’t release a wild boar into a store to create a commotion so they could steal the book. Well, I think that would be great actually. Though, I would feel sad for the boar. And maybe someone will get hurt! But maybe there is something more to say. Maybe in its humor it evokes a disenchantment with notions of ownership, of rules and laws, of commodities and inventories, of the loss of independent bookstores. Maybe there is a nostalgia for a gray area where something like gleaning can exist. Where taking an apple from a tree is not a crime (I know a book is not an apple). Or an advocation for free circulating knowledge, for libraries. For economies and exchanges not based on the transaction of money, but of gifts. I don’t know. I don’t claim any of this in this work. The work is a joke. But I feel sad for the person who has never stolen a book.

ÀM: Waves can provoke ideas of impermanence, yet standing through them is also resistance. Can we be both the authors of waves as well as their resistance?

DH: I want to think of the wave itself as resistance.