Philip Morris (now called Altria, since 2003), the maker of the world’s most popular cigarette, Marlboro, is credited with being an early pioneer in corporate giving. In fact, for four decades, countless arts institutions across New York City had long considered them the most reliable source of corporate funds and they consistently ranked amongst the top corporate contributors to the arts in the city. At one point, they were contributing $7 million a year to more than 200 cultural organizations in New York.

Directors of cultural organizations across the city likened their sponsorship to “the Good Housekeeping seal of approval.” Other funders saw what they were supporting and it opened doors for additional funding.

However, a handful of artists and health advocacy groups have long taken a more skeptical view of Philip Morris’ donations and what its motives actually were. They insisted that the company’s philanthropy bought it a better image, while silencing those who would normally speak out about the public health problem caused by tobacco.

They also argued that Philip Morris used its power over the cultural institutions it supported to try to sway public opinion and serve its corporate interests.

For example, in 1994, when the New York City Council was considering a bill to ban smoking in public places, Philip Morris asked arts groups that it funded to put in a good word for them.

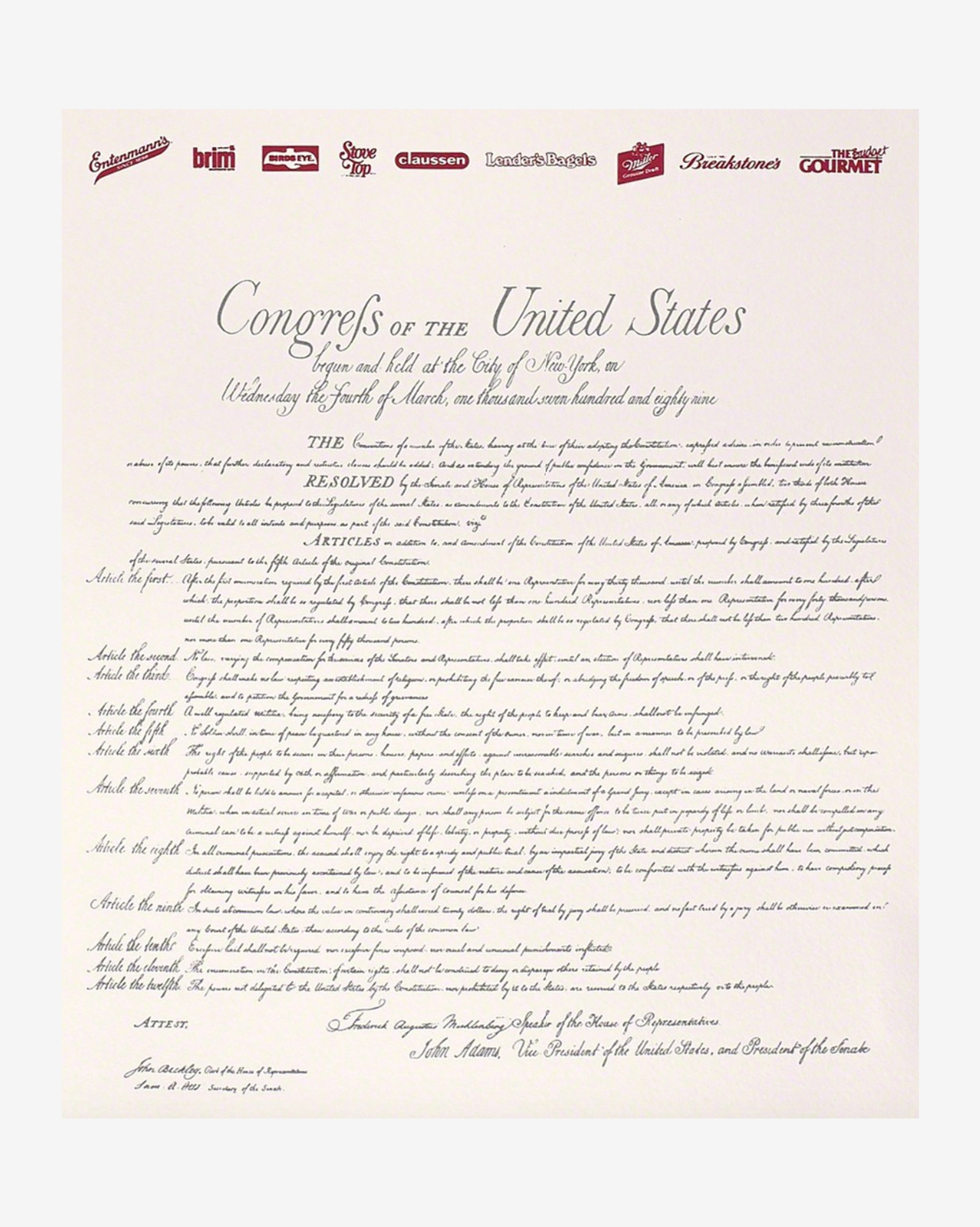

In addition to supporting the arts, Philip Morris was also very politically active in states where they held subsidiary companies. In 1989, they paid the U.S. National Archives $600,000 to use the Bill of Rights in a $60 million public relations campaign which they sent copies of for free in Philip Morris logo-emblazoned tubes. They vigorously supported the election campaign of North Carolina’s Republican Senator, Jesse Helms, who campaigned vigorously against the National Endowment for the Arts, opposing Federal financing of artworks he considers obscene. He was hostile towards minorities, AIDS victims, homosexuals, and women’s rights.

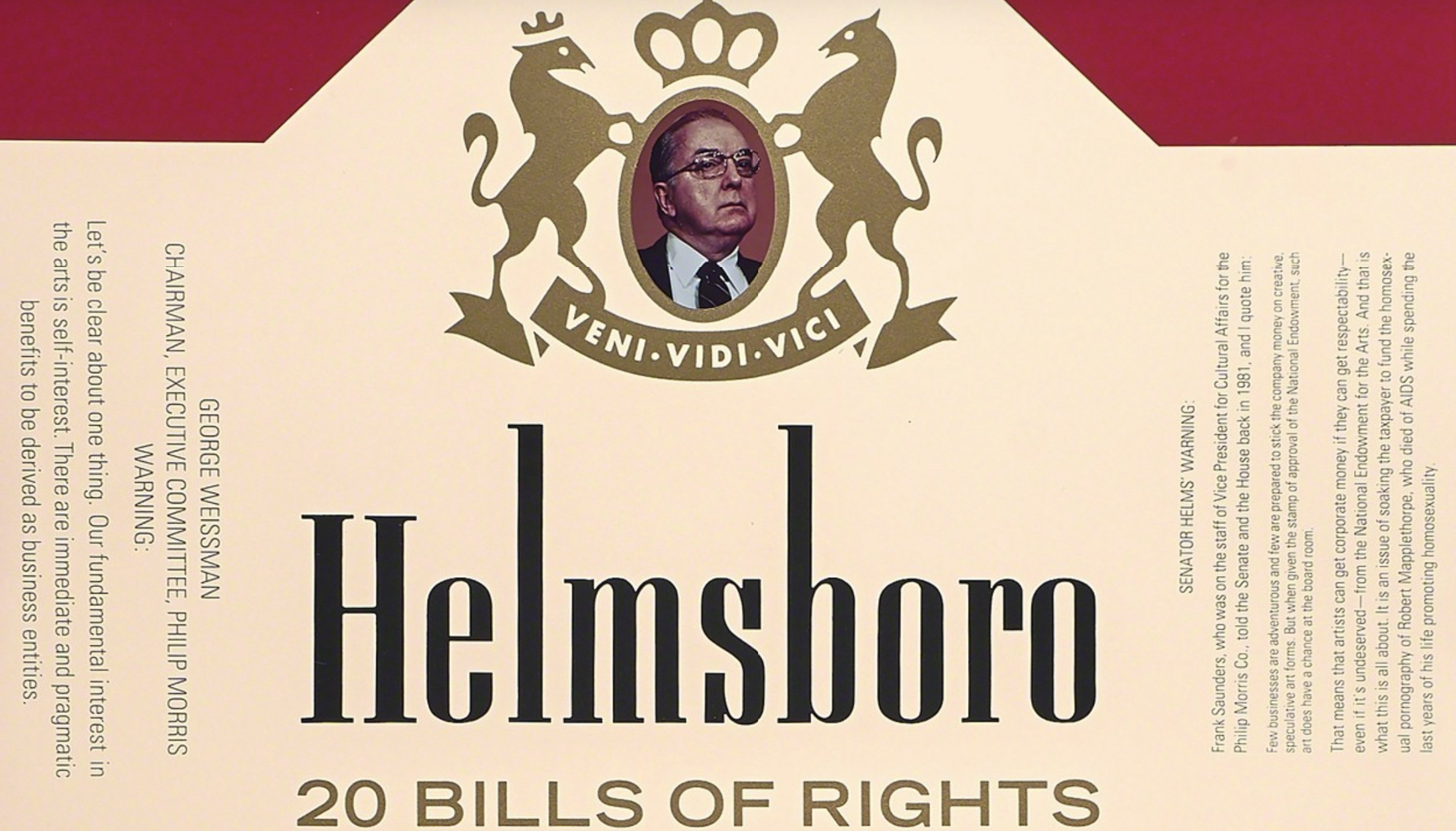

The support of Senator Helms caught the attention of German artist, Hans Haacke. In 1990, Haacke created a monumental flip-top box of cigarettes to exhibit in the John Weber Gallery in Soho.

At first glance, Haacke’s work appears to be of a Marlboro cigarette package. However, upon closer look it shows “Helmsboro” written in place of Marlboro’s brand name. A portrait of Senator Helms appears in place of the ”P.M. Inc.” medallion, showing his alliance with Big Tobacco. ”Philip Morris Funds Jesse Helms” is written on each cigarette and the box has affixed to it a copy of the Bill of Rights.

Along the side of the box, in an area usually reserved for the Surgeon General’s warning, there is a statement from Mr. Helms taken from the Congressional Record of Sept. 28, 1989:

”That means that artists can get corporate money if they can get respectability – even if it’s undeserved – from the National Endowment for the Arts. And that is what this is all about. It is an issue of soaking the taxpayer to fund the homosexual pornography of Robert Mapplethorpe, who died of AIDS while spending the last years of his life promoting homosexuality.”

In addition to this statement, the box has a 1980 quote from George Weissman, the former chairman of Philip Morris: ”Let’s be clear about one thing. Our fundamental interest in the arts is self-interest. There are immediate and pragmatic benefits to be derived as business entities.”

Shortly after the work was made, Philip Morris threatened the John Weber Gallery with legal action if it exhibited Helmsboro Country. The gallery defied their threats and went on with the show.

End.

Sources:

New York Times, As a Company Leaves Town, Arts Grants Follow

Paula Cooper Gallery – Hans Haacke: Helmsboro Country

New York Times: A Giant Artistic Gibe at Jesse Helms

This article is part of a series of special features for the exhibition ‘1-31’ curated by Adam Carr.