An extensive selection of Frédéric de Goldschmidt’s collection is currently being exhibited on Collecteurs.

The French-born, Brussels-based collector Frédéric de Goldschmidt doesn’t follow many trends, instead he relies on his own instinctive attraction to things. To him, trends and movements are temporary forces that often openly illustrate general illusions of freedom and human ideals. He prefers to stick to his physical world—at times, a presumably isolated and remote occurrence, nonetheless ever-evolving and autonomous.

Aside from continuously acquiring works that further his thought and imagination, Goldschmidt regularly shares his collection with the public at his fairly new space in downtown Brussels; a former mental institution that offers not just an underlying, tangible biography for artists to explore ideas, but an audience’s unconventional way of experiencing pieces as well. Goldschmidt demonstrates the idea that art should always be shared, and challenged.

Collecteurs: Collecting has always been important to people in your family, like your grandmother. Did this part of history influence your personal approach to collecting?

Frédéric de Goldschmidt: I inherited an Impressionist work by my grandmother, which I sold in order to start my own collection. I certainly inherited my grandmother’s love for art and for artists; she was a supporter of the Berlin art scene in the 20s. In the 10 years I’ve been collecting, my interest and support for contemporary creation has certainly grown stronger, yet it was always there from the beginning.

Collecteurs: What does it mean to be a collector in the 21st century?

FdG: I’m not sure it’s that different to be a collector in the 21st century, than a collector in the 17th. The Dutch patrons of Vermeer or Italian patrons of Caravaggio, played a significant role in the life and career of the artist. They also influenced art history, having recognized talent beyond those painters that were typically favored by their contemporaries.

Collecteurs: How has the general sense of collecting evolved? And where will we go from here?

**FdG:**There’s a trend towards the dematerialization of society. To some extent, it applies to art as well. Collectors could end up with less physical ownership, possessing works virtually.

Collecteurs: I agree with your statement about us moving towards a non-physical world. It makes me wonder, though, about the essence of things, like collecting. What does it ultimately mean to collect? Merely owning things — physically or not — or does it also involve the prospect of continuously fostering a relationship with some or all of our five senses? When does something turn into a collection?

FdG: Property is no longer what it used to be. First aristocrats, and later bourgeois patrons of the arts in the 17th to 20th centuries typically owned castles, lands, and factories. Art was hung inside these properties or in the churches they supported.

Today’s fortunes are mostly immaterial, like stocks that deal with immaterial services themselves. Therefore, it would make sense if collectors would own artworks that remain in freeports, and their enjoyment is limited to the moment of buying and simply knowing the work is theirs.

Since I don’t have that type of fortune, my enjoyment continues being much more traditional. Although I’ve acquired more works than my walls can handle, I enjoy rotating and changing works by lending pieces to an exhibition, or other things. I regularly present works in my collection to the public. I feel it’s a responsibility towards the artists and their galleries to share my appreciation with others.

Collecteurs: You are exhibiting and managing part of your collection on Collecteurs, what other forms of exhibiting have you explored so far?

FdG: The exhibitions I’ve organized have been pretty classical—brick and mortar.

Collecteurs: Aside from global access, what else can be gained by moving exhibitions online?

FdG: Virtual exhibitions require much less effort and make it easier to experiment with different things. One is able to address more themes and make exhibitions with works from other institutions, or works that otherwise would be impossible to obtain due to logistic or financial constraints.

Collecteurs: An imaginary utopia for experimentation, I can see the attraction. Yet, once everything is possible, I wonder if discourse doesn’t become disinteresting, and somewhat irrelevant. What do you think would change in the art world if collectors were truly connected to and in contact with each other? Would they have more control over the market? Would it generally benefit the market’s well-being?

FdG: Collectors can help each other by sharing discoveries that are based on mutual appreciation of their respective tastes. They have a role in supporting creativity and maintaining diversity. I think it’s the individual personalities of collectors that make the offer diverse and the market vivid.

Each collector has their own biography and taste which will create attractions to different works. A collector typically goes for what they want, no matter what. That’s not always the case with juries or acquisition committees who have to take into consideration the other members — a reason why they tend to be a bit more bland. Similarly, one should be careful and aware that connectedness could eventually lead to uniformity.

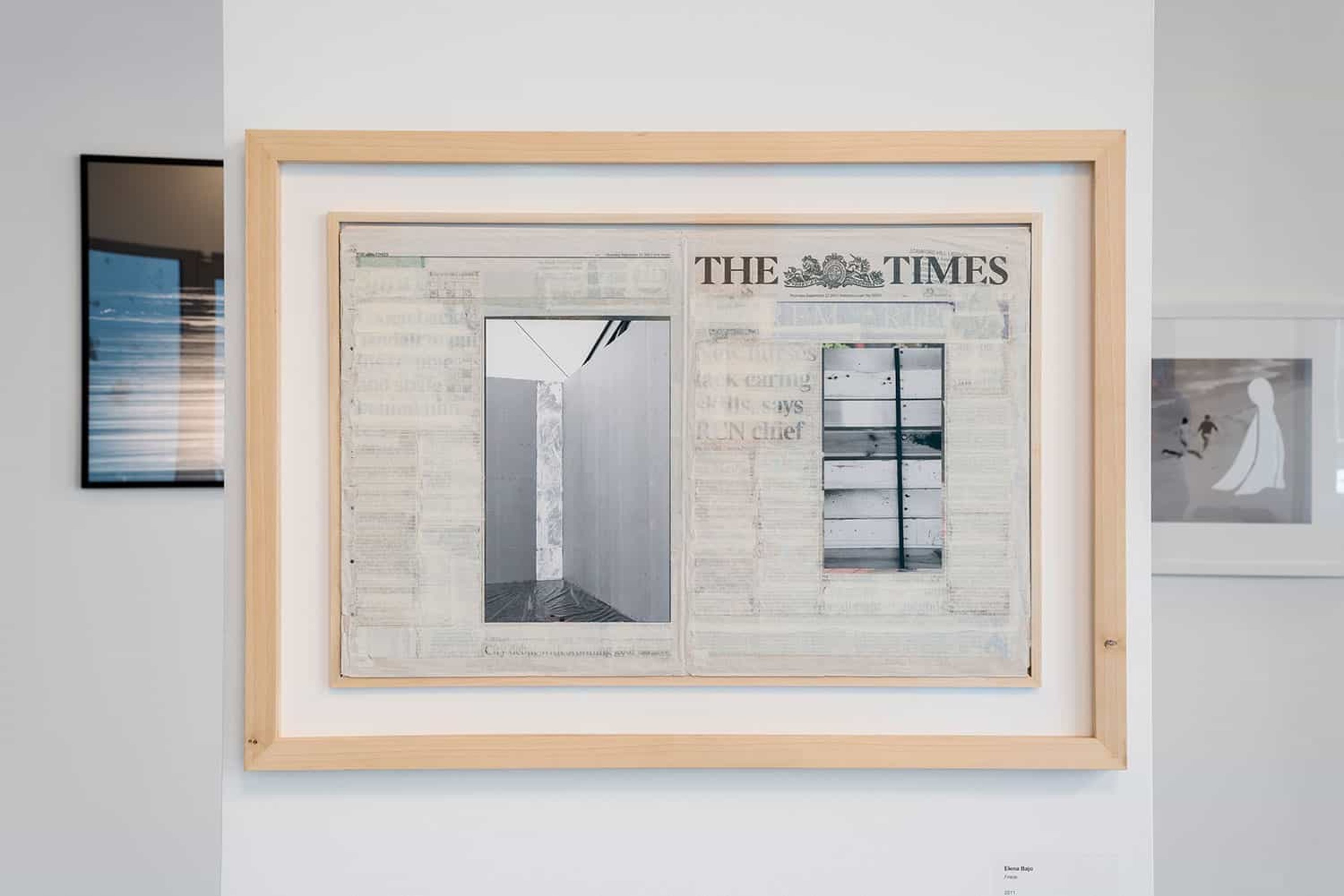

Various artworks from White Covers, Brussels © Jef Jacobs for Collecteurs

Collecteurs: That’s a good point, connectedness potentially leading to uniformity. I suppose it also depends under what circumstances connectedness takes place; if there’s enough room for tolerating individual exploration and growth. A question, perhaps, that we could ask ourselves: how can we foster human connection without abandoning our individuality?

FdG: It’s not connection that impedes individuality, it’s the tendency to follow trend that comes now with connection. One shouldn’t share things merely to comply with public appreciation. This is also why private collectors must fully embrace the fact that they don’t have to report to anyone and don’t depend on public funding or taste. That’s why they should only acquire works according to their impulse and show what they like, not what they think the public will like.

Humans perform tasks differently according to their cultural and social environment, but overall there are different ways to fulfill the same functions. It’s this diversity that makes humans human.

Collecteurs: What are some things in the art world that aren’t working as well as they should? And what can be done in order to improve them?

FdG: The discrepancy between the market value of the most recognized artists and less recognized artists is way too high. It’s not good for artists in their 30s or early 40s to be sold for six or seven figures. And vice versa, that great names from 20 or 50 years ago, who are a little overseen by the market, would sell for less than bright kids just out of school.

Elena Bajo at White Covers, Brussels.

Serena Fineschi at White Covers, Brussels. © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Collecteurs: Are some practices just outdated now?

FdG: The way galleries work is certainly outdated in the age of the internet. But in today’s world, curation and physicality is even more important. I want to see a show in a physical space, just like I enjoy listening to an enthusiastic gallerist talk about their artist.

Collecteurs: How do you visualize the online art marketplace or auction house of the future?

FdG: A dematerialized marketplace where trusted professionals show, sell and buy artworks that are checked and vetted by experts can function well for artworks that can be easily compared. Though, I have a problem imagining how to replace the lower and upper end of the market via an online marketplace. I think the physicality of the public presentation remains important for younger artists who need and deserve to have their work shown in real life, and experienced by people other than collectors. On the other hand, a public presentation is important for masterpieces that deserve to be appreciated in flesh by as many people as possible.

Collecteurs: You make sure to catalogue your collection. What are some of the benefits of being so thoroughly organized?

FdG: It’s important to know what’s in the collection, where it’s stored and how much it’s worth in case of damage or loss. It’s also about exploring different opportunities with a collection, not just the sharing between walls. Careful cataloguing makes virtual exhibitions also possible.

Collecteurs: Your exhibition Not Really Really , that is being exhibited on your Collecteurs account, was housed inside a former mental health facility, which you had acquired a few months before. Was and is the former history of the place important to the exhibition’s central theme?

FdG: I didn’t know the former history of the building when I acquired it at a public auction. I left everything intact for the first exhibition and the last show of my collection; it gave everything an uncanny atmosphere, a ‘borderline’ between art and everyday life. It was nice to experience the space this way, before undergoing extensive renovations. I owned almost every work before acquiring the building and deciding the theme of the show.

Alongside my co-curator, Agata Jastrząbek, we played with ambiguity by installing works in unusual places. One of the commissioned artists, Loup Sarion, was directly inspired by the building and did an installation of a sofa and chair whose cushions were filled with cement. He called the piece Don’t lie on me and it was shown in a room whose door still carried the name of its in-house psychiatrist.

TO SEE: Frédéric de Goldschmidt’s latest exhibition, White Covers, can be viewed on Collecteurs and also is in the framework of Private Choices, an exhibition organized by Centrale for Contemporary Art along with 10 other Brussels-based collectors. Curator Carine Fol chose, for the art center and for the collector’s space, works where the color white hides or reveals a reality or memory.