“Multitudinous Seas” exhibition at Fondation Hippocrène, Paris until December 16th, 2018

Phenomenon 3 will take place in Anafi, Greece, 1st-14th July, 2019

It was the summer of 2015 when scientist Iordanis Kerenidis and ethicist Piergiorgio Pepe officially set off on their ambitious endeavor Phenomenon: a contemporary art biennial on the Greek island of Anafi. Hosting a residency for an array of different artistic practices, this remote biennial creates a discourse around contemporary art and its idyllic natural setting. Phenomenon recalls a seemingly far gone organic interaction with art; all the while asking life to just slow down. The biennial’s visitors have no other choice but to remain within their surroundings and contemplate the right here, the right now.

Kerenidis and Pepe—a couple that has been collecting since 2006—believe in the possibility of a society in which the cultural elite begin to actively acknowledge the matter of privilege; asking them to take responsibility for the very nature of their inherent freedom. Having grown receptive themselves to their fortunate position in the (art) world over the past decade, the duo have taken action by realizing public experiences like Phenomenon, allowing for human existence to materialize—and to (hopefully) evolve.

Collecteurs: Starting off with something you once said, “… we’re constantly trying to reinvent the role of the art collector.” What does it mean to be a collector? And is this role still alive and practiced genuinely today?

Iordanis Kerenidis and Piergiorgio Pepe: Indeed, we try to reinvent the role of the collector as a creative social agent in the art world; an active, scientific, political actor who constantly provides new conditions for artists to create work that opens the world to new possibilities.

Through the art we collect—and the artists and projects we support—we hope to question concepts like normativity and privilege, and aspire to having a real social affect. This doesn’t imply that we primarily support or collect politically engaged art. Rather, we’re interested in art that conceptually challenges the conditions that enable these predominant systems of representation to appear unquestionable and natural. It’s in the interstice between the political and intimate where art generates forms of resistance, and our role as collectors is to support precisely these dynamics.

It isn’t always easy, especially since collectors are often pigeonholed as passive subjects whose collecting amounts to nothing more than a glorified passion privée, to quote the famous 1995 private collections exhibition at the Musée de la Ville de Paris.

Even more recently, the press release of a collectors’ exhibition at WIELS in Brussels—an institution we deeply respect—described the private art collections on display as “_the fruit of years of curiosity, care, and passion._”

At first, there’s nothing wrong with this description; after all, being curious, careful and passionate should be part of any endeavor. But here is what we believe is missing from this list: research, critical thinking, rigor, political agency, social responsibility. If even in the mind of the most cutting-edge institutions, private collecting is still somehow perceived just as an expression of a passion, then we, collectors, have quite a way to go!

Of course, the fact that nowadays a collector is also someone who purchases artworks as a financial investment, with the goal of acquiring a social status, or as a branding strategy for their luxury goods industry, makes things rather complex. We certainly do not want to claim that there is a good and a bad way to collect. Far from it. But what becomes evident is the vacuity of the term “collector,” which, as any other fixed role or identity, is but another way of normalizing, assimilating, making itself innocuous. On our side, painfully conscious of our own privilege and bias, we try our best to destabilize this role, deterritorialize it, undo it, without any aspiration or hope for grandiose changes. Yet being conscious of the importance of experiencing, experimenting, resisting, and reinventing it again and again.

© Theo Prodromidis for Collecteurs Magazine

C: Perhaps this rather fixated way of perceiving and defining a collector is also a consequence of collectors themselves. Some of the many collectors I’ve spoken to in the past don’t want to see or analyze themselves further than their passion for art. Or so it seems. Perhaps they don’t want to consider themselves more vital within the art world’s setting and whatever exists beyond all of that, other than the role of the financier and appreciator of art? Or, is it just more comfortable to not assume responsibility?

KP: No one should feel the pressure to analyze or justify themselves. Financing and appreciating art is a formidable act indeed. But we could also be aware of the consequences of blindly and self-contently supporting an art market that has become pretty much a luxury goods industry; in the sense of utilizing the same communication and financial strategies, where the majority of artists are unable to make a decent living of their art, where more and more mid-sized galleries are closing down, where most public museums are forced to put up blockbuster shows of “star quality” artists financed by their mega-galleries, where corporate-backed foundations are imposing their rules of the game.

The art market will of course continue to exist this way as long as the socio-political conditions that produce it—namely that of neoliberalism—go untouched. At least our goal, and thankfully that of collectors, artists, scholars we know, is to ensure that there’s a vital space for alternative economies and micro-strategies that destabilize the system and let art actualize its emancipating potential.

“We see art as a way to offer non-normative experiences, overcome established hierarchies, generate unexpected relations and as a force for social change. In this sense, supporting art, in any way imaginable, is a necessity. ”

C: Empathy was the first word that came to mind when I started to contemplate your relationship to art. Can you relate?

KP: It’s interesting that with the word empathy we go back to passion—pathos in Greek, the root of empathy. Somehow it’s inescapable when talking about patronage or mécénat in French. Both of these notions have very interesting connotations, actually.

Patronage has the same root as patriarchy, paternal, etc., rather directly alluding to the notion of an ‘empathetic,’ yet patronizing white male in a position of power. Same with the mécènat, from Maecenas, a “wealthy and generous Roman advisor and important patron for Augustan poets,” in other words a patron showing empathy only to poets praising and supporting the regime of emperor Caesar Augustus. That’s some pretty heavy baggage for collectors to leave behind!

To answer your question more directly, we want to think of our relation to art as a social responsibility and engagement more than empathy or benevolence. We believe in the potential of art to create new imaginaries, different ways of thinking and looking at the world. We see art as a way, possibly one of the most effective ones, to offer non-normative experiences, overcome established hierarchies, generate unexpected relations and a force for social change. In this sense, supporting art, in any way imaginable, is a necessity.

© Theo Prodromidis for Collecteurs Magazine

C: With the arrival of fourth-wave feminism, #metoo era and the refugee crises, did your sense for social responsibility shift in any way?

KP: It has become increasingly difficult to try and make sense of the world we live in. There’s a profound crisis of democracy, the result of decades of neoliberal policies that have disenfranchised and exploited vast parts of the populations that are now finding shelter in extreme, populist ideologies. In this pretty grim context, it’s ever more necessary for those of us that retain their privileged position (but for how long?) to accept accountability, seek alliances, and be a force for eradicating exploitation at all levels. In other words, there has been indeed a shift in intensity and urgency.

C: I think the location of Phenomenon makes a lot of sense, especially if one of the main goals is to aid the origin of unexpected, new ideas. What has been one of the most rewarding yet unexpected outcomes in these last two biennials?

KP: Phenomenon is a biennial project for contemporary art that we have been organizing on the island of Anafi, Greece since 2015. It includes a residency with performances, lectures, video screenings and other events, as well as an exhibition throughout the island. The history and the myth of the island, as well as its current context—rather than its ‘essence’ or ‘idea’—are at the center of the project itself.

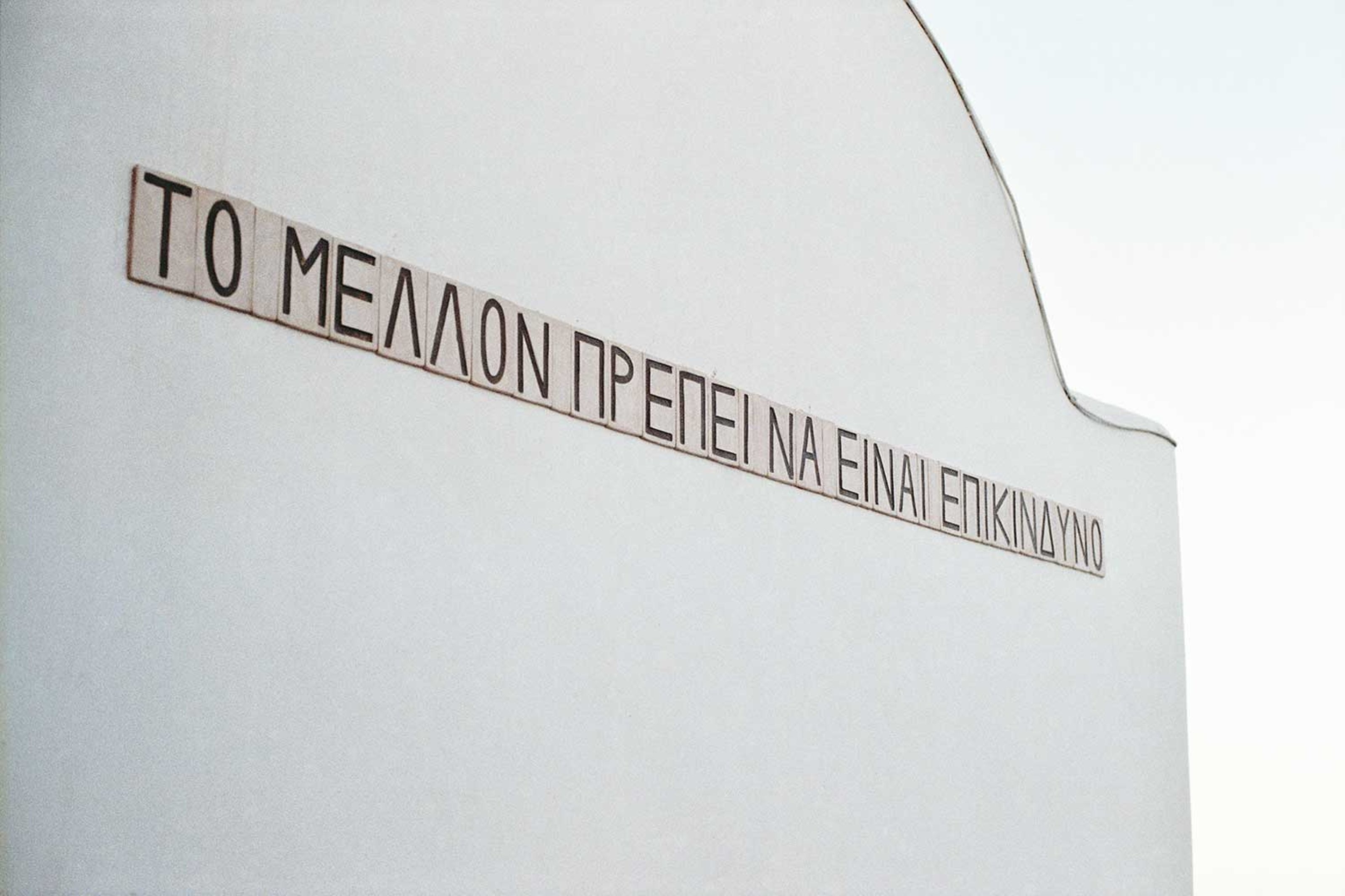

On this remote island—suddenly revealed by Apollo in order to provide a haven for the Argonauts—the project wants to explore contemporary art as a way to reveal the invisible, to blur the apparent, to access previously unimaginable worlds. In particular, Phenomenon is interested in how collective and personal stories are socially constructed and renegotiated. In this respect, Anafi—at its small but revealing scale—is at the center of the project as a typical example of cultural stratification, where the temple of Apollo discreetly serves as the foundation of an Orthodox monastery, while the story of the dictatorship exiles held at Anafi cohabits silently with local history.

We have been questioning the forces that actualize the visible and discursive, that build historical formations. How can we reinvent history and denaturalize the dominant narrative? Starting from Anafi, its history and its present, the project aims to explore the circulation of images through space-time and pleads for a multiplicity of partial and irreducible archaeologies.

C: So actually, the island itself becomes an active participant during Phenomenon.

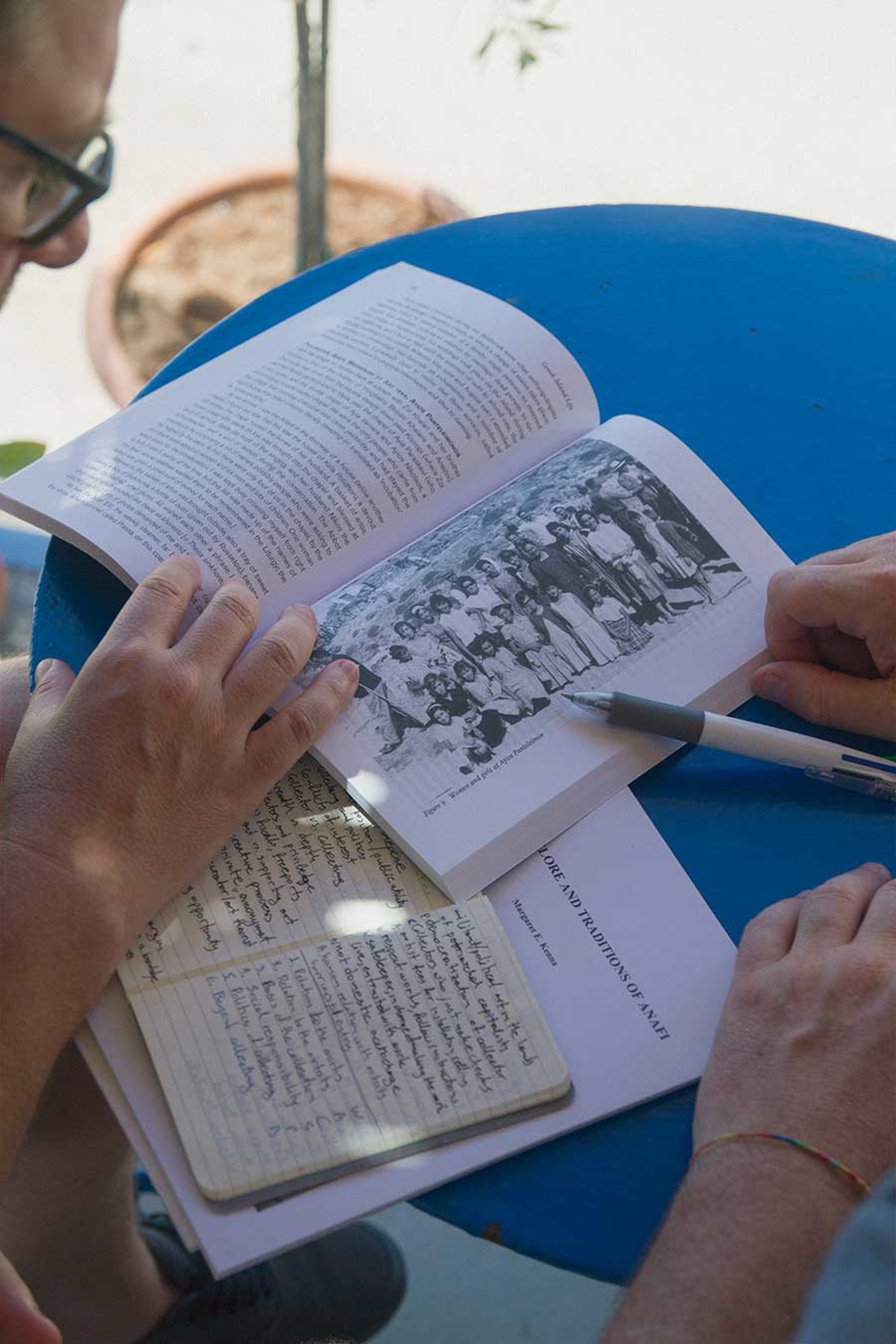

KP: Definitely! A goal we set from the very beginning has been to involve the island not as a stage or a postcard, but as a main participator. We’ve dedicated significant focus on researching Anafi’s history and context, and have shared this research with the artists and the islanders. We have also closely cooperated with a British anthropologist, Professor Margaret Kenna, who has been conducting research on Anafi for more than fifty years, so that Phenomenon can pursue its ambitious artistic goals in a way that remains respectful and aware of the local context.

Of course, the temptation to idealize Anafi, as a location, is very strong, as the concept of a “remote island” has been deeply rooted in the collective literary imaginary. We have tried to look differently at this matter by refocusing on the fact that Anafi is a real place, with a real history and a contemporary focus, and with a population that constantly questions its present and its future, its location as a European periphery, its demographic decline, the scarcity of its environmental resources, its relation to tourism.

Since the idea of Phenomenon was born, it has been imperative for us to work closely with the inhabitants of Anafi, first of all by asking them if they were even interested in hosting and participating in this project. Since then, the municipality, the businesses, the artisans, the people of Anafi have been increasingly more involved in various aspects of the project and today seem very proud of hosting Phenomenon. For example, a year after Phenomenon 2, several artworks are still visible in the public spaces and the inhabitants look after them with dedication. In addition, five Anafiots have made their way to Paris especially for the opening of our recent Phenomenon exhibition at the Hippocrène Foundation. This unexpected level of support from the local community has been extremely gratifying and touching for us.

Another rewarding outcome has been how Anafi and Phenomenon have affected the invited artists and participants both in terms of their practice and at a more personal level. It has been so moving to see many artworks created for and from the Phenomenon experience. Artists like Ignasi Aballí, Kosta Bassanos, David Gustav Cramer, Dora García, Mario García Torres, Nina Papaconstantinou and Julien Nédélec, to name but a few, have created works that integrate historical or visual elements of Anafi. For many of the participants, the time in Anafi has remained with them and they continue to talk about it as a unique personal and creative experience, as the beginning of new connections and relations amongst them. For us, it is just incredible to have been able to collaborate closely with all these inspiring participants and create such strong relations, both professional but also personal, that continue to flourish throughout the years. We feel truly privileged.

Finally, the most unexpected outcome has been the warm reception and recognition that the project has received in Greece and internationally, which has gone way beyond our expectations when we conceived Phenomenon back in 2014. Most recently, for example, by receiving the Montblanc Arts Patronage Award.

“Sometimes we spend weeks or months discussing an artist’s work before we decide to acquire it. We see this decision not only as a one-time buy, but as a pledge to support the artist in the long run.”

C: How has your scientific profession influenced/shaped your relationship to art?

KP: We are pretty sure it has at some level.

For Iordanis, as a scientist, it’s important to start with some intuition. But that’s never enough. One needs to delve into the details of the work, understand the big picture, put things in the right context and try to make informed decisions. This is how we try to construct our collection as well. Sometimes we spend weeks or months discussing an artist’s work before we decide to acquire a work. We see this decision not only as a one-time buy, but as a pledge to support the artist in the long run. As a quantum expert, it has also affected the way we look at how art deals with the notions of time, observation, visibility.

For Piergiorgio, as an ethicist, it was essential working on understanding the context of Anafi, and the implications of the relation with the island and its inhabitants, avoiding the trap of ‘appropriation’ and ‘colonization.’ While this is a question that, despite the best efforts and intentions, is never fully resolved, we keep raising and addressing it as best as we can. His long-term experience as a business ethics professional and his work as lecturer in business ethics and art market ethics at SciencesPo has also influenced significantly how we position ourselves in the context of the art market.

But the influence goes both ways. Our experience with art and artists has significantly enriched the way we see our profession and our careers as well. After all, it’s in the space between art, science, and philosophy where creation happens.

C: Referring to some constraints in terms of experiencing art in the everyday, I’m quoting you: “Appreciating art can and must be a creative and emancipatory experience.” Can you unfold this thought?

KP: Art can indeed be an emancipatory experience on many different levels. For example, some of the questions we try to bring up with our project Phenomenon is what it means for contemporary art to operate in peripheral places outside the institutional art world and away from established curatorial practices, and how one can avoid exoticizing, lush fiestas or pretensions of exchange of knowledge. We’re very much aware of the complexity and importance of finding a place of convergence between Phenomenon’s aspirations and the fact that the inhabitants of the island recognize themselves in the project. It’s extremely difficult but necessary to address the binary notions of center and periphery, local and global.

“It has become pretty clear with the world’s political situation that we don’t have the luxury to ignore what’s happening around us, we all need to engage socially at levels that surpass ourselves and our private circles. Art has a role to play. Collectors too.”

We were also confronted with these ambivalences between the imaginary and socio-political reality of the island when we were asked by the Hippocrène Foundation to make a Phenomenon exhibition outside Anafi, more precisely in Paris. We can’t hide the fact that when we first heard about the Foundation’s proposal, we struggled with how we could ever transport the experience of Phenomenon to the center of Paris!

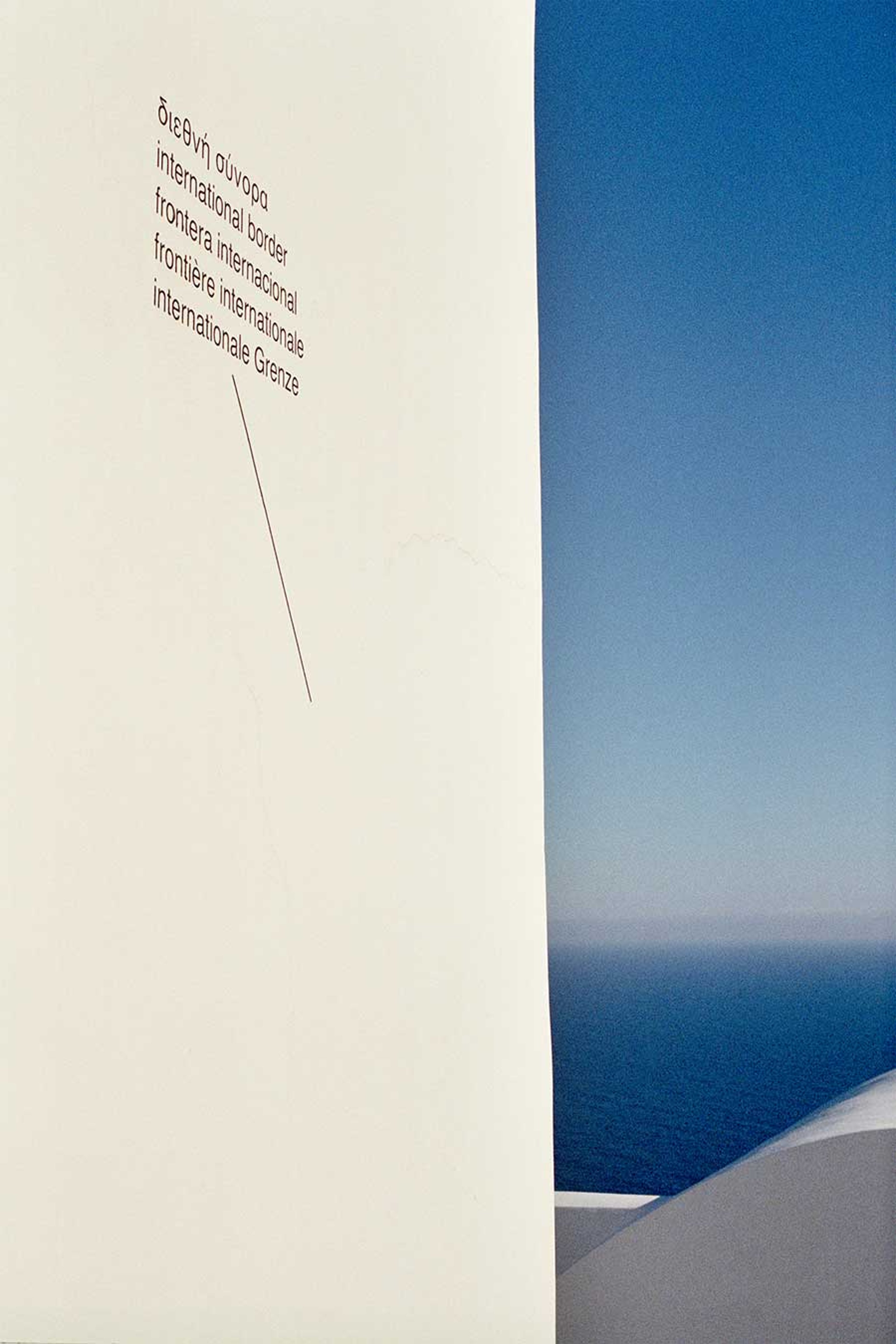

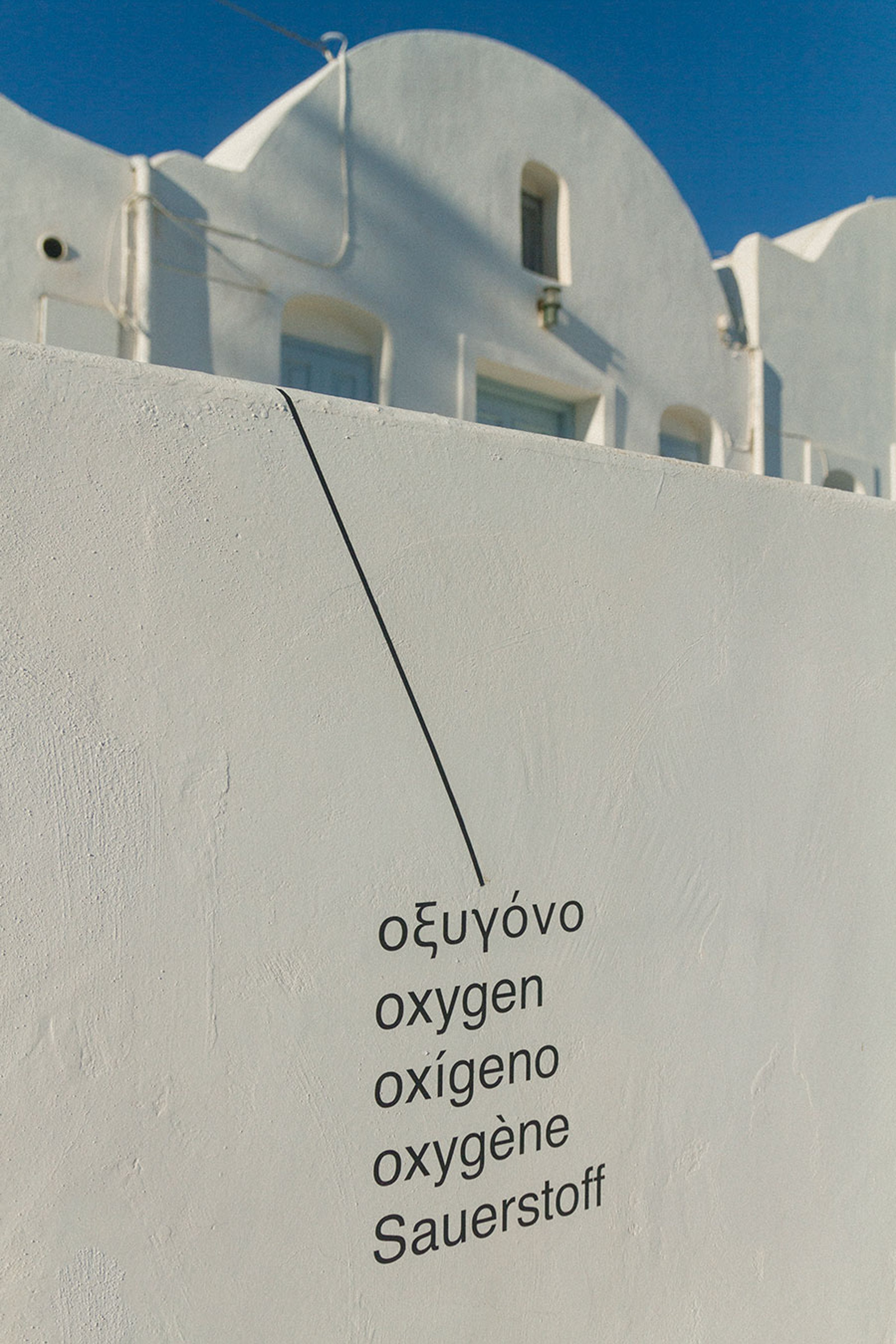

Instead of giving in to our self-doubts, we’ve decided to cooperate with curator Grégory Castéra — one of the participants of Phenomenon 2 – share this questioning with the artists, and make the exhibition precisely about that, namely about the types of possible strategies that can destabilize such binary constructs, like periphery and center, North and South, citizens and refugees.

One reason that such binaries are perpetuated is that the corresponding words have been so strongly associated with their stereotypical properties or adjectives — the civilized center, the lazy South, the job-stealing refugees, etc. The project tries to disentangle such categories from their normative associations and create differential and unstable connections, as an emancipatory exercise.

How else to talk—in the center of Europe, about Greece or the financial and political crisis—other than trying to undo stereotypes and propose new unions and meanings? The idea was triggered by the only voice recording of Virginia Woolf, that we used to conclude our live presentation of Phenomenon 2. Woolf underlines that it’s very difficult to use certain words, because they have contracted so many associations in the past, so many “famous marriages.” Using Shakespeare’s Macbeth as a reference, she goes on to wonder, for example, who can use the word “incarnadine” today without thinking of “multitudinous seas.” This, in fact, gives the title to the exhibition, Multitudinous Seas.

To return to your question, experiencing art can emancipate the viewer by challenging them to interact with different world views, find points of convergence, and continue questioning and reinventing ways of resistance. Lately, it has become pretty clear with the world’s political situation that we don’t have the luxury to ignore what’s happening around us, we all need to engage socially at levels that surpass ourselves and our private circles. Art has a role to play. Collectors too.

© Theo Prodromidis for Collecteurs Magazine

“We understand the risk of talking about abusive power when we ourselves are coming from a point of privilege. But we believe it’s everyone’s responsibility to stop ignoring these issues, and the art world might be a good place to start.”

C: Perhaps a collector’s first role is to accept their position, and deal with it responsibly. Effective, lasting change can never materialize if everyone continues being ignorant towards their very own privilege. Isn’t openly voicing one’s own privilege more productive rather than ignoring it? Having power doesn’t need to be a burden, it can bring along positive change.

KP: You’re absolutely right that the position of an art collector is that of a privileged actor in the art world. Generally, collectors don’t have to struggle to make a living out of art, as all art professionals need do, and beautifying this position as one of a passionate, benevolent appreciator of art, is precisely ignoring this fact.

Collectors can make or break artists and have a monetary power that can become very easily abusive. The need of the art market for an incessant flux of money, especially at a time where the public funding continues to decrease, generates dependence from private collectors and lowers the level of scrutiny over their practices. How about instating artist fees for private reselling of artworks, enforcing stricter regulations for freeports or against conflicts of interest?

For example, in any other sector, avoiding conflict of interests is a basic standard, while in the art world collectors can own at the same time collections, auction houses, museum-like foundations receiving public funds and probably use all of the above as a powerful promotional machine for commercial goods.

It might be uncomfortable, as you say, but for how much longer can the art market continue to ignore its need for a more granular set of deontological standards? We understand the risk of talking about abusive power when we ourselves are coming from a point of privilege. But we believe it’s everyone’s responsibility to stop ignoring these issues, and the art world might be a good place to start.

© Theo Prodromidis for Collecteurs Magazine

C: As long as money is involved, people will try to make as much of it as possible, with the least amount of effort… that’s the course of human nature ever since money has been introduced.

KP: This is exactly when we realize how powerful capitalism is, when it has convinced us that running after profits and disregarding the social impact of our actions is a natural human activity. And this is again where art has a big role to play, in de-naturalizing such narratives. It’s interesting that even in the US, people like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez are coming out as democratic socialists, which it simply means that our priority as humans should be ensuring a decent life for everyone rather than maximizing our personal profit. It’s as simple as that.

C: So how do we actively inflict change, even if just on a small scale?

KP: The question of acquiring agency is certainly a complicated one. On one hand, we need to create alliances and work together to amplify the impact of our actions. At the same time, we need to keep in mind that these communities stop being effective the moment they crystallize behind fixed identities with revindications of normalcy and inclusion. It’s a continuous process of forming multiple intersecting alliances to inflict change and undoing them only to start again.

C: You mention the lack of deontological values within the art market. But maybe it needs to start with its key forces imposing actual change; and in some sense I’m especially referring to artists here. Or am I wrong at giving artists too much responsibility? I just think some or many artists must have contributed to the problem, mainly feeding into neoliberalism … it can’t just be the consumer. Can it?

KP: We all play a role, the artists, the collectors, the press. The art world is no different than any other sector or the world in general. There are people who profit from it and the vast majority is trying to survive. Putting blame on one or the other is not conducive to making things better. What we need is intelligent alternatives, building different economies, and this is already underway both in the art world and in general. Artist-run spaces, non-profit galleries, independent collectors are providing ways of destabilizing this all-for-profit art market and propose creative ways of constructing new collectivities. Not all is lost!

C: What type of art is needed in order to create discourse that surpasses the institution’s periphery, and its elite? Do we live in a time where we need art to shock in order to create a reaction?

KP: It’s true that we’re becoming more and more anaesthetized to anything that doesn’t fit in our comfort zone. But art that aspires to shock may not be the solution. After all, life itself is far more shocking! From the “shock and awe” campaign used by Bush to launch the disastrous Gulf war, to shock politics as the new norm under Trump’s administration to perpetuate a state of exception, we don’t see the need for art that aims at shock value, no more than for art that is content to reproduce a post-truth (or post-internet) reality without any commentary.

The real force of art is the creation of affects and percepts, these transfers of intensities that happen when someone looks at a work of art and realizes that they’re not the same person anymore, that something changed in the way they perceive the world, in their ability to act politically and challenge the conditions that perpetuate the master narratives. Just consider the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres and how the political and the intimate reinforce each other and construct new ways of resisting and breaking free. Or that of a new generation of artists, for example Alejandro Cesarco, Christodoulos Panayiotou, Haris Epaminonda, who find this affective quality in a non-hierarchical circulation of floating images, navigating between personal memories and sociopolitical events, or artists questioning established systems of representation, like Detanico/Lain or Chrysanthi Koumianaki. This is the art we relate to and wish to support.

C: It’s especially worrisome, this continuous reproduction of post-truth.

KP: Yes, we live in an era where truth has lost its convincing capital. Just look at the lies the US President can get away with or the invasiveness of fake news. The internet has enabled the proliferation of information, ensuring at once plurality of opinions and new means of propaganda. It seems like we fought all too well to get rid of the notion of absolute and universal truth in favor of partial perspectives, only to get ourselves into the “anything is as true as anything else,” even the earth being flat! It is not clear how to get out of this conundrum but regulating social media seems more and more necessary.

C: In terms of your private collection, how does it interrelate with your general goal for Phenomenon?

KP: They are two distinct activities that serve the same goal, namely to support the art. This support comes from acquiring works in order to constitute a collection, and also from organizing projects like Phenomenon. There are of course similarities in the way we work, for example in both cases we try to collaborate closely with the artists and continue acquiring a body of works throughout the years. And of course, many of the artists from Phenomenon become artists of the of the collection and vice versa.

C: And lastly, out of what need did Phenomenon start to become a reality? Were you feeling some kind of lack in other biennales?

KP: What we felt was missing was mostly a creative and socially engaged role for the collector. At times we still get comments of the form “But this is not what a collector is supposed to be doing!” We cherish these moments, it means that to some extent we are pushing the normative boundaries, finding lines of flight, turning the passion privée into social engagement. But of course, there is a lot more to be done. On our side, we will continue this summer with the third edition of Phenomenon (1-14 July, 2019), where we will try to understand the role of art and of cultural actors in times of political urgency.