Since 2014, the Venet Foundation has been home to Bernar Venet’s impressive collection. From his foundation’s growing complex—located in the picturesque Le Muy commune in southeastern France—the artist spoke with Collecteurs about starting the Venet Foundation and what it’s like to be both an artist and a collector.

Watch the interview below:

videographer: Malo Delarue

Evrim Oralkan (EO): It’s fair to say you have one of the world’s most impressive art collections, developed through exchanges with fellow artists like Donald Judd in the ’60s and 70’s. When did it start to become the collection as the world knows it now, and when did you get the idea to open it to the public?

Bernar Venet (BV): I never had the idea of collecting, really. The idea of building up a collection was never my goal, not even, even less to make a foundation one day. It’s just that I was very friendly with those artists you know. And our work in those days had absolutely no value. We were meeting together in lofts and having drinks, having dinner, talking, “Oh yeah, that’s a cool piece, that’s a good one. You know what? I’d like to have that, do you want a piece of mine?” We were making exchanges, not with major works but with pieces like this [shows with his hand] you know.

But I’d always dreamed to live in a museum. Each time I go to the MoMA, to a big museum, and I see all those major works, I think to myself, my God, if I had my bed installed here it would be my dream. So then I started to think that it would be nice to have one or two artworks from my friends—notably, you said Donald Judd, but also Sol LeWitt. Sol LeWitt was making exchanges with all the artists. He was an extremely generous artist. If you were relatively good, it was very easy to make an exchange with him.

Donald Judd was my neighbor, he was living just around the corner, and I knew him already since 1967. We had many points in common. He liked to collect himself; he also liked to be surrounded by furniture that he was making himself. He was interested in architecture also. So, we had many things to discuss. Although I was much younger and I was a little kid with them, they liked me because I had a good eye. But most of the time they were exchanges or exchange in a little bit of money when I started to make money. For me, money in the bank doesn’t mean anything because I see that the banks are collecting art with my money, so why don’t they take my money and I buy the art myself? But, of course, I was buying that for almost nothing. I remember buying the famous Diagonal of 1963 by Dan Flavin for $1,000. Got sold for $950,000 recently. It’s just that nobody wanted those things, I knew that they were very important so why not get one, you know, put it here. I have pictures of my kids playing around the Dan Flavin Diagonal in question.

So, it started like that, and then when I moved to the South of France, to Le Muy, I still did not have the idea of starting a foundation. I just moved there because I needed a place to put my collection. There was a factory and there was a mill. I started to bring my artworks and put them in the mill. I had Motherwell, a masterpiece of Motherwell, I had many works by Robert Morris, several Sol LeWitt, and so on, several Frank Stella. So it was great, it was cool to put them around me.

Artwork: Fred Sandback – ‘Pedestrian Space’ exhibition view, the Venet Foundation, 2017. Photo credit: Frédéric Chavaroche – Bernar Venet Archives

Image (left) : Donald Judd – Untitled, 1972. Photo credit: Bernar Venet Archives

But then, one day, what happened is that the museums started to come and visit. Friends of museums, you know. And I was so surprised that they were coming to see my work, of course, but then they always enjoyed looking at the collection. So I had those beautiful Ellsworth Kelly pieces, and Ellsworth Kelly was a friend.

And most of the time, there is also this idea that the artists were making work a little bit for me. It’s not always the case, but very often it does happen. So, I always had stories to tell people and then, one day, I started to think, “My god, the property is starting to be beautiful!” It was getting bigger and bigger, you know, I was buying all the neighbors and building more houses and everything. So, I started to think it would be ridiculous but if one day I die—which is something that could happen because it happens to everybody—so I thought it would happen to me probably, it would be stupid if my kids have to sell that and to sell the artworks to pay taxes. So, I talked to them, and I told them that it would be much better for them to have the foundation in their name because the foundation is not Bernar Venet, it’s Venet. So, it would be great to have a foundation in their name with the collection remaining there; we don’t have to sell anything. And we thought that it was a very good idea so we would not inherit it, which is a great thing, but we would have all the works available for them.

EO: There are collectors who are highly motivated to share because they understand the artworks are meant to be shared, but there are also those who are very resistant to the idea. Why do you think that is, and what were your main motivations in opening your collection to the public?

BV: Collecting is very nice; it’s great, it’s beautiful to be surrounded by artworks. I have a tendency to think that works of art, when they are really important, significant—when they belong to art history—they don’t belong to a person who has them in his home. Yes, it’s great you made money and then you bought art and you can enjoy it, but in the end, I think art should belong to everybody.

My philosophy is very clear. I was born in a place; we were very poor. I won’t tell you the details, but it was really a poor family, and so I started with zero. Then, I was very lucky to live in a social context—I insist on this word “social context”—that allowed me to first go from my little village in the mountain to Nice, and I met Arman, and thanks to the fact that I went to school—social context again—I could communicate with him. He appreciated me, he took me to New York, and I started to meet other artists and became friendly with them. Everything was going “well well well,” you know, things were growing all the time. Exhibitions, retrospective exhibitions at the age of 30, and then building up this collection, all of that is thanks to a social context. So, this social context makes me think that everything I have, everything I did, everything I own should go back to society. It’s the minimum that I can think of, so I give back everything to the foundation.

EO: You’ve previously said that your neighbor Donald Judd’s vision for Marfa was what inspired you to create something exceptional, which became the Venet Foundation. What are the similarities and differences between the Judd Foundation and the Venet Foundation, as well as between Marfa and Le Muy?

BV: Talking about Judd’s foundation is a very good subject because I have some interesting souvenirs. As I told you, I was his neighbor, and very often we were together. I remember visiting him and one day he said, “Bernar, look at what I am doing.” And so we went to the little corner, it was a little dark, and I remember him showing me slides of what he was doing in Texas, in Marfa. He was going to install a lot of works and perhaps make a foundation. And I remember him showing me the slides one after the other in the corner of his loft.

That same day he asked me, “Bernar, why don’t you come and spend a week with me? I’ll show you what we are doing, it’s fantastic!” I mean, Judd was someone I admired, but I also have my work, and I didn’t find the time to do it, I neglected to do it. Today, I wish I would have done it, although I spent enough time with him in many places. But when I went there after his death, I realized that what he did was absolutely spectacular, and I understood completely his ideas. But it is true that we do art and we exhibit this art in galleries and museums, and not very often can we really get exactly what we want. The dimensions, the space are never good enough for what we do. And we also have a tendency to work for those spaces, you know, where if we create our space, then we do what we want. And then this idea came a few years later, when I was in Le Muy:

“Oh my God, how about how about developing all of that?!” And today, I can make some installations in the middle of the room. It’s very satisfying.

Phillip King – Slant, 1996. Photo credit: Bernar Venet Archives

The difference between Judd’s foundation and my foundation—it’s very clear. I mean, we are in two different landscapes, that’s one thing. First of all, you know Marfa is in the desert, and you know it’s very whole, very brutal, very difficult, but at the same time you know those buildings are spectacular. You see art and you are not distracted by anything; all you see is art.

When you come to my place, it’s more French. The landscape is so amazing; people come to visit sometimes just for the landscape. We have this river of waterfall trees which are absolutely spectacular, and everything is very, very beautiful. I am closer to Monet at Giverny than to Donald Judd, in a way. But at the same time, you get there and you have a very good demonstration of what recent art is about, was about. Also, we have been able to make some very spectacular installations of artists from the ’60s and ’70s.

EO: So, you live between New York and Le Muy. As you said before, the artist shapes the place, but the place shapes the artist too. How did Le Muy change you?

BV: It is true that the context, the spaces which are available can shape the artist. About 10 years ago, I had a building for myself with a lot of space, and I could install some sculptures which were already relatively physical. As soon as I started to use Le Muy… I have this factory which is about 2,500 square meters, or 25,000 square feet, and thanks to that space I can really install some major works and also change those installations regularly. I have been able to make extensions to that factory. It is true that the artist is creating the ideal space, and it is also true that when you find yourself in such a big, open, empty space, any dream can be realized.

If I had not had Le Muy, I’m totally convinced that I would never, ever have been able to develop my work the way I’m doing it. You know, if you visit Le Muy, we have a piece which is 200 tons inside the building. I have a piece which is about 150 tons outside, I have another one which is 180 tons, again in another space, and then, of course, I have many others. I have been able, for example, to take the Sculpture of the Versailles, dismantle it, and make something else out of it—what I called “Effondrement,” which is like a collapse, you know, like the arcs. So, it’s wonderful to have a space like this and to be able to use it the way I want.

EO: What is your vision for the future of Le Muy, and where do you see it in the next 20 years?

BV: Le Muy, as a foundation, at this stage… I’m just putting all my money in and I’m not asking anybody to help, and I believe that the way I am organized, if I’m lucky enough to live another 30 years? Ok, 20… I will be able to develop it a lot, really. I mean, when you see what I have been doing in the last four years, for a private person, it’s a lot. Acquiring all those Frank Stellas—I have 24 Frank Stellas now, and this chapel designed by Frank Stella is something very, very spectacular. All that was done in the last five years. This huge James Turrell piece is also something very spectacular, the collection. So, this is what I did in four-five years. Things are getting better and better for me, fortunately, and I hope that in the next few years I will be able to really do a lot more. Acquiring more land and installing major artworks. I know that Le Muy’s going to develop a lot.

The question sometimes remains, you know, what is going to happen after me, when I’m not selling my work? Well, I have some ideas about that. I have a way to resolve it, but I also think that if I do something which is so exceptional, and today already in France it’s being recognized as one of the main spots, the main foundation to visit… I’m totally convinced that the country or someone will follow up. You can’t just abandon such a collection and such a site.

EO: What is the percentage of your works being presented as opposed to other artists’ works?

BV: There is definitely more of my work than the work of others, but the collection is in the mill. For example, already you can visit a living space with major artworks, and then there is one park which is completely devoted to other artists. You’ll find Anthony Caro, James Turrell, Frank Stella, of course. Then you have Phillip King, the British artist. You have Arman, you have Tony Smith, you have Sol LeWitt, Ulrich Rückriem, the German artist. We have a lot of major works; they are not little toys.

Image: Sir Anthony Caro – Skimmer Flat, 1974. Photo credit: Bernar Venet Archives

EO: Most works in the collection are personalized for you by your artist friends like Francois Morellet, Frank Stella, James Turell, and Fred Sandback. Do some of them stand out in terms of their stories, and can you share a story with us?

BV: You see, the idea of collecting for collecting does not interest me. Because I could think tomorrow, “This is a great artist, how about getting him?” It’s really that what I have in this collection is very much my taste. Not just that it’s a matter of family. I don’t have artists except for one or two exceptions. Most of the time because my wife bought them and after that, I bought them for my wife. She has her collection; I have my collection. But normally, they’re all my friends. So, it’s really a family thing. For people to understand one of those artists, we need to see the work of the others, and to understand my work, you need to see those artists and vice versa constantly. It’s really a family story. You will really see something that doesn’t belong to this family. So, for me, it’s very, very important. This is what makes the difference between my collection and other collections. Then it is also true that many artworks were done for me.

Robert Morris – Untitled, 1969. Photo courtesy of Christie’s Paris.

For example, when I got married, I asked Arman to do a garbage piece. He was making little garbage pieces like this in the late ’50s and early ’60s, and I said, “You know, these works are so important, Arman, could you make one for me?” and he says, “But I’m not doing that anymore.” “Yeah, okay, so you could make one for me, but I want a big one.” So he made a huge piece. And then, from that new piece, 10 years after he had stopped making them, he decided to make an entire series. He developed a series of garbage pieces like this of Sol LeWitt, Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, everybody. So, that’s a good example of where the artwork was made for me.

But, also, Francois Morellet—it’s really like a portrait of mine, where he used the letters of my name V, E, N, E, T, and because of the position of those letters in the alphabet, it created the position of the angles that he put in the piece. Or, sometimes, it was not made for me but, you see, like Ellsworth Kelly, the day he found out he knew I had this blade piece; beautiful artwork in steel, wall piece. Then he made a drawing for me, he re-designed it. Same thing with Motherwell. The day I told him that I own that piece A la Pintura # 5, he said, “But Bernar, this is the best of all my paintings of the O_pen Series_,” and he made a little drawing again. So I have many examples like this. Of course, Frank Stella, it’s not that he made pieces for me; he made a chapel for me. I like that, I like this context, you know, it’s very important. That’s why, when you visit the collection, you really get into a special, particular context. It’s very much like Marfa, you know—you will not see, as much as Judd and I, we respect the work of Andy Warhol and Lichtenstein, it’s not the kind of thing that we would collect.

EO: What are the most notable differences between being and artist and collector as opposed to being a collector only?

BV: I don’t know, I would have to have a… To tell you about the difference between a collector-artist and collector-collector, I would have to be the two persons at the same time, and I cannot do it. I’m just the artist-collector and not obsessed with collecting. I collect only because I want my friends around, and I collect because I prefer to have artworks than money in the bank, let’s be clear about that.

But, you see, a real collector is going to think in a very scientific way. He’s going to think, “If I have that and that, I should also have that, and also I should extend my collection and give visibility” and so on. Me, I’m not obsessed with that; I just don’t think about buying, but if one day I go to… I had dinner with Frank Stella yesterday, and I told him: “Thanks, but I didn’t go to your studio this afternoon; otherwise I would be too poor to invite you for dinner.” You see, I go to the studio of an artist or I see something that really is my taste and I cannot resist, I just take it. There are many artists that were collectors, people like Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, but also Rauschenberg was a collector. In the past, Degas was a collector—he was spending his money before he even sold his work; he was always in debt to acquire artwork. These artists who do that usually have a vision, an interest in art history. We don’t collect to decorate our wall; we really want to be surrounded by meaningful, historical artworks.

EO: Are you still mostly exchanging works to grow the collection, or do you acquire works, as well?

BV: In recent years, because I wanted to really acquire some major pieces—museum-quality work— most of the time I paid for what I wanted to get. I just see it and I say, “I want it.” But I’ve been making some exchanges.

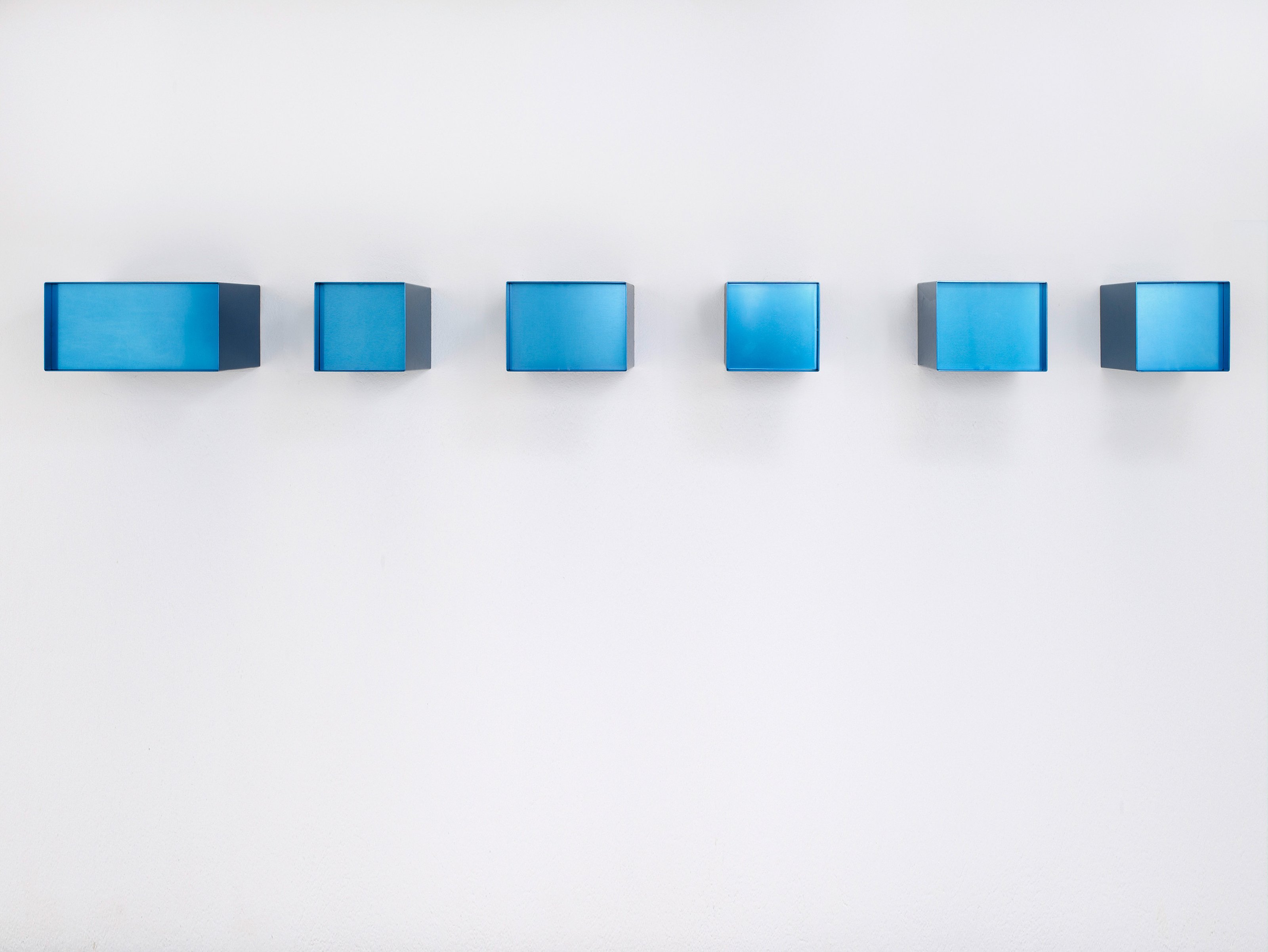

For example, last year we made an exchange with Larry Bell. I got a huge piece composed of three huge cubes. 1, 2, 3—it’s like nobody, nobody in the world has a piece as big as that of Larry Bell. Usually, when you have a piece of Larry Bell this big [demonstrates with hand], you’ll be happy. He came to visit and when he saw the space he said, “Bernar, don’t worry, I’m going to do something for you.” But the examples are not as often as they were in the past.

EO: Do you acquire mostly the established artists you already know, or do you look into any emerging artists?

BV: You see, the collection is really about my generation because very early I understood exactly what those artists were about, and I understood immediately that they were in art history definitely; there was no doubt. Today, it’s very difficult when you see what’s going on—there is so much and it goes in all directions. To understand what is really significant is very difficult; also, it’s not my taste. I have my limits; my brain and my education and my culture were good enough to make me understand very well and very early because I was also doing the same thing as the artists of my generation. But, today, I don’t get it. I see some people, some artists who are very creative, but I always see a relationship with things that I saw in the past. I must say that, the ’60s and ’70s… The ’60s mainly were so rich, so radical, so new! At that time, it was so exciting to be involved in the ideas of the young artist. Talking with Carl Andre, Smithson, Michael Heizer, and all those guys, it was so enriching. We all had things to say which were totally new. Nobody ever thought like us. We were saying things that were never conceived before.

We were not sure if it would be art in the future, but we were thinking it’s possible, why not? How about that? Today, it looks like it’s too obvious that it’s art, and that disturbs me a little bit. To tell you one thing, you know I like to collect art that doesn’t look—for the people in the street—like art. Those people, they will just pass by a Carl Andre on the floor; they would not understand it’s an artwork. They would see a Richard Long on the street, and they would not understand that it’s an artwork. This is what I like; I like things which are most secret but also very serious, not like decoration and things, which are immediately pleasing and convincing as artworks for anybody on the street.

End.

Image: Larry Bell – Something Green, 2017. Photo credit: Maxime Bruyelle/Bernar Venet Archives.