We’ve asked several participating artists in The Wave to expand on their relationship with the sea. Below find the full transcriptions of the interviews that consider fluidity and the mobile essence of this liquid expanse and its many metaphors, meanings, and associations.

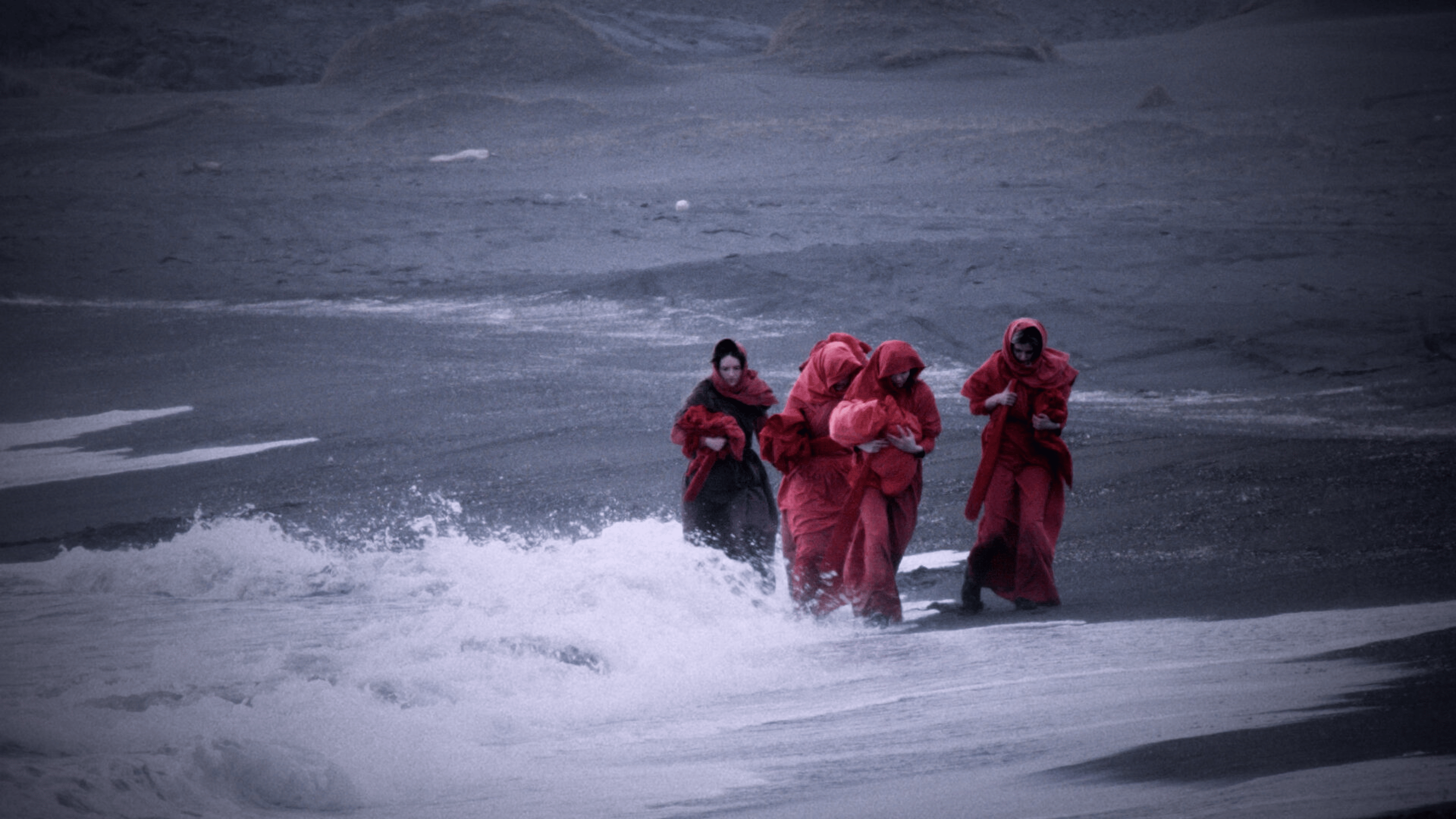

María Dalberg / Uncontainable Truth, 2021 (Video still).

Elizabeth Gallón Droste and Daniela Medina Poch / Intersecting Mediterranean(s) from its Regional Rivers I, 2021 (Excerpt).

DANIELA MEDINA POCH

For me, the sea is my grandmother. I mean this metaphorically, but also not metaphorically. My mother's mother spoke with the sea. She lived in San Andrés, which is a Colombian island surrounded by the Caribbean Sea. When she passed away, her ashes were thrown into the sea. Amongst the many adventurous professions she had, she was a scuba diver and she taught me and all of my cousins to enjoy the sea and to treat it with respect and wonder.

In the months that I visited her, the movement of the tides and the waves stayed with me. They rubbed me until I fell asleep every night. If I close my eyes, I still can feel this tide and this wave within me. I remember the salty taste and the freshness of the ocean in contact with my skin. I always enjoyed watching the sky from below the ocean. The dialogues between the sunlight and the water are mesmerizing—conventions become malleable; patterns of liquidity are hypnotizing.

The sea, for me, is an immersion into a world with other logics, another sense of gravity, another palette of color, shapes, dimensions. I guess the sea has been always guiding me to surrender to other forces, to acknowledge other water-based logics and perspectives, and it will always be a channel of communication with Maria Mor, my grandmother. For me, water is this miraculous phenomenon, a space of complexity, of contested realities.

In my text “Aqualiteracies: Understanding (And Sensing) Water As a Hybrid Data Carrier,” I describe water as a living archive. It carries, produces, and sustains information in itself: water in relation to its chemical and physical environments; water in relation to human and more than human bodies; water in relation to hybrid temporalities; water in relation to living systems and even to socio-economic and ecological constructions. Through the investigation around Intersecting Mediterraneans (2021), I became more aware of the tremendous phenomenon of the ocean than I was before, especially its ability to process, regenerate, and keep its living conditions amongst the channels of information and waste that also reach the ocean.

This research also made me aware of water’s fragility and it makes me angry to understand water and rivers and oceans as areas for waste disposal and the created fiction of its disappearance. In Intersect Mediterraneans we understand water as a living archive of these relations. Water sustains human and more-than-human hybrid temporalities.

Elizabeth Gallón Droste and I understand the sea as a projected surface of contested and disputed futures appropriated as a commodity. We approach the Mediterranean as a plural and salty watery body mass that connects a network of sweet bodies of water which flow into each other. During this project, our aims contribute to a wider reassemblage of the identities and imaginaries around Mediterranean cultures and its plurality by gathering intersecting stories, myths, anecdotes, and intuitions of the Po, Isonzo/Soča, Neretva, Cem Cijevna, Düden, Kishon, Nile, Medjerda, Chelif, Moulouya, Ebro and the Rhône rivers.

Elizabeth Gallón Droste and Daniela Medina Poch / Intersecting Mediterranean(s) from its Regional Rivers I, 2021. Photography by Elizabeth Gallón Droste and Daniela Medina Poch.

We aim to contribute to the acknowledgement of the specificities of the context and life rules that nourish the Mediterranean. Through The Wave, curators Carolina and Àngels invited us to develop a trailer or teaser for Intersecting Mediterraneans. The challenge of translating a large scale five channel multi-media installation into a trailer, which could include and synthesize the complexity of the piece, was interesting for us. Elizabeth and I took the decision to work around immersion and fluidity. We worked with a music composer to develop a sound composition, which included and merged fragments of these Mediterranean stories and recordings of the sea. This translation gave the work unexpected layers and also facilitated the access of the work to a digital audience.

It also allowed us to see works from other participating artists. I perceive a dialogue with the work of Pınar Ögrenci, especially A Gentle Breeze Passed Over Us (2017) as she also understands the Mediterranean as a site of contested realities. Ögrenci states that the Mediterranean doesn't belong to those who were born there, but to those who go through it, those who were immersed in it and have experienced its waters and ghosts.

I also perceive a connection with María Dalberg's work which is a clear dialogue about the intersectional aspect of the work, about gender violence and the historical silencing of certain narratives and perspectives. Both works—María’s and ours—attempt to amplify female voices and to denounce systematic violence. Another work that inspires me is the video of Enric Farrés Duran, who shows a multiplicity of approaches and formats, which always trigger me to examine topics through unexpected lenses.

BEATRICE ALVESTAD LOPEZ

Hi, I'm Beatrice Alvestad Lopez and my work, Elemental Bodies, (2020), is in The Wave. I'm going to talk a little bit about the sea. My earliest memory of the sea is from my summer holidays in Spain as a child. I used to play in the sand a lot with my twin sister building castles and burying ourselves in the sand and watching the waves. There’s definitely the feeling of expansion of the sea and in a way, it is playful. It may be romantic, but this is how I saw my earliest memories of the sea.

The sea feels like a landscape— it is a part of our planet, covering most of its surface. And so, I feel very tiny in comparison to the sea. As you can see in Elemental Bodies, I work with the sea as a landscape and a healing force, exploring it in relation to myself as a human body and its nurturing aspects. When I am at the beach pouring water in the glass tubes, these containers are almost like bodies in themselves.

There is this constant nurturing of water going in a circle. Whether we are nurturing plants or whether the rain is nurturing us and the water is nurturing us, we have a circular/symbiotic relationship to the sea. At the end of the video, I immerse myself in this sea, which is a very refreshing and powerful feeling. Then, I go up to the shore and lay on the pebbles that were heated by the sun. This fire feels very strong and like an energy rising through me. Many scientists say that it is good to have a dip in cold waters and it makes us happy. So, Elemental Bodies is an activity or ritual that shows that.

Beatrice Alvestad Lopez - Elemental Bodies, 2020 (Excerpt).

For me, the sea is movement. The sea is the non-visible and everything that is in constant motion. It comes with this difficulty of trying to grasp what is in constant motion. There is no right and there is no left and there is no top and no bottom. There is no fixed perspective and that's very exciting to work with. Everything is in a continuous flux.

My narrative is not linear—it's circular. The bodies have no order. When I represent or relate them they are entangled, they are in a constant relationship and a porous state, and they are free. They have no weight, they are light, they are suspended, and that's very exciting to work with. These bodies are interrelated and connected with each other in the same space.

For me, the sea is not just a physical space—it is a vision, a state. Since I began to work with these ideas (for instance in Chaos Dancing Cosmos in 2016) I started to create immersive experiences, a stage where the visitor and the artworks relate with each other. All the surfaces become a continuous porous materiality where everything contaminates the other: the visitors, the artworks, the sound, the light, everything. It is all part of the same chant or melody. So, the concept of the sea has always been a part of me.

Rosana Antolí / A Tube Under the Sea, 2020. 150 x 110 x 250 cm. Resin, methacrylate, copper, brass, sand, mediterranean stones. Photo courtesy of Gallery Luis Adelantado, Valencia. Photography by: David Zarzoso.

Rosana Antolí / I Will Give You the Sea, 2020 (Excerpt). Video HD, Digital Colour Sound, 9’40”. Music by Tomaga. Photo courtesy of the artist and Gallery Lehmann+Silva, Porto.

My video work I Will Give You the Sea (2020) is like an offering. There is something very attractive and poetic to me in trying to grasp something that is ephemeral or in constant motion or that cannot be tangible. Suddenly, to have this title like I Will Give You the Sea becomes a utopia because it cannot be. For me, the artwork functions in a poetic way with the characteristics of what the Sea represents to me. It creates a “what if” scenario.

With the sculpture A Tube Under the Sea (2020) the concept is the same. It is about what it would be like to grasp a part of the sea: what if we could extract a wave and put it inside of a museum or inside of a gallery. That was the research behind it. I created a shape where I speculated about the movement of a wave to catch it.

The work of other artists (in this exhibition) includes a kind of recognition that we are searching for the same thing but taking different paths. There is always a connection when I find another artist that has an interest or passion about things that I am also passionate about. I am curious to see how they are choosing a path that is different to mine to arrive at similar ideas and conclusions. For me, that is the curiosity I have behind all of their methodology. That is what connects my work with their work.

My earliest memories of the sea are from my childhood. I have always lived close to the sea and I listen to the sea while sleeping. Often, the sea becomes part of my dreams. I use the sea as a symbol in many of my works. For my film Uncontainable Truth (2021), I used embodied history to channel the words of women that have been lost in history. My film is taken from five testimonies of female defendants, and the aim was to give back their voices that they were consistently denied. The film brings their names to light through spoken stories recorded in old manuscripts and other contemporary sources.

I strongly relate the film Mnemosyne (2010) by John Akomfrah. Both his film and mine reflect on systematic structures embedded in society that lead to invisibility and quieting of minority groups with a weaker status.

María Dalberg / Uncontainable Truth, 2021. Video installation.

MARIE FARRINGTON

How do you interpret landscape's effects on culture, architecture, and life? Is it a neutral or determining factor in ways of life? What are the positive and negative aspects of such relationships?

I think of landscape as being tied to ideas of both process and visibility. The idea of landscape as opposed to land implies a kind of framing and incorporates the act of looking. So, there's something participatory there that I'm really interested in. Landscapes have their meaning articulated in the processes that give them form; questions of visibility become concerned not only with how to represent such spaces, but how to encounter them and facilitate a kind of co-creation with the site.

Rather than reading or representing landscape as other or as external to cultural production, I think there's something really generative to be found in inhabiting a space between the human and the non-human, and cultivating the reality, generating potential that landscape can offer architecture or culture more broadly. What I find so critical about this is how landscape can work towards a collaborative involvement in production. It becomes implicit in its own representation. And this goes beyond cultural representation. For example, scientific field study’s immersive nature reveals the co-creative potential of landscape and the ways in which cultural forces or scientific procedures or sampling methods are co-determined and produce new realities developed in conversation with landscape.

This process opens up the scientific method to the effects of entanglements and affinities and speculative agencies hinting at an opportunity to reframe how landscape is coded and to acknowledge it as an active and determining agent in human affairs and within imaginations and images of itself. The continuous process of becoming that landscape engages in establishes it as a partial place that is emergent rather than absolute.

Marie Farrington / See, Level, 2019. Sculpture. Courtesy of Brian Cregan and Fingal Arts Office. This work belongs in the Irish State Art Collection.

The reciprocity of its material exchanges results in something that's more akin to a temporal event than a thing. This kind of unfolding or becoming results in a very slippery refusal of category: there's a tension between making and unmaking, or between intactness and disarray that I'm really interested in, and this tension challenges the assumption that the world is composed of discrete objects and bordered entities. Landscape reveals the impossibility of drawing clean categorical edges around pieces of matter.

What are your earliest memories of the sea? Was it a place of interest or a place of anxiety?

My earliest memories of the sea are in relation to healing. When I was five, I fell and cut the palm of my hand quite badly on some glass. I was brought to hospital to have my hand stitched and bandaged. Weeks later on a trip to the beach, I accidentally let salt water and sand clog the bandage while I was playing in the water. When we got home, my mother was quite horrified when she opened the dressing because she saw an almost rusted looking wound. But, we soon realized that this was how my hand was healing—the salt water had healed the site.

Throughout my childhood, my grandmother had a fondness for collecting sea water to bathe her feet in at home. We would peel the labels off old plastic bottles and fill them up whenever we went to the coast, taking them back to the Midlands. She believed in the restorative nature of salt water and the benefits of soaking her skin in it. I remember that sweet-ish briny smell of decomposing seaweed whenever we opened up those bottles of water.

These memories have led me to associate the coast with the skin. I like to think of the beach not as a static mapping of a boundary, but as a porous margin that continuously revises its own structure. Both the coast and the skin are these sites of intense contact, and they both act as momentary archives. Kind of recording interferences and tactile crossovers and historical residues while also shedding and undoing and washing over and rebuilding their own fluid architectures.

Could you offer some thoughts about your approach to water as space? For example, it is often viewed as either a location or a conduit. Does your approach favor one or the other?

For me, water is inherently transitional, so I think of it as a conduit or as similar to a state of waiting. Water has a quality of active in-betweenness, so its future action is latent within its current action. There's an idea of interdependence built into water too: it's a carrier of other materials and narratives and shared histories but its form is amorphous, so it's structurally dependent on the vessels or landforms that contain it or carry it forward.

This quality of interdependence makes thinking about water as a location quite tricky because water doesn't necessarily present self-sufficient or fixed parameters. The idea of location implies a place that can be mapped or navigated in a way that is spatially predictable and has distinct established spatial facts. Water erodes this idea of location in that it redefines place as a set of fluid and transitional interconnections across space and time. Water is destabilizing because it presents shifting sets of qualifiers whose momentary or dynamic unity puts forward this proposition of place without the promise of a stable or essential material reality.

What's the place of the sea or water in your work, both literally and metaphorically?

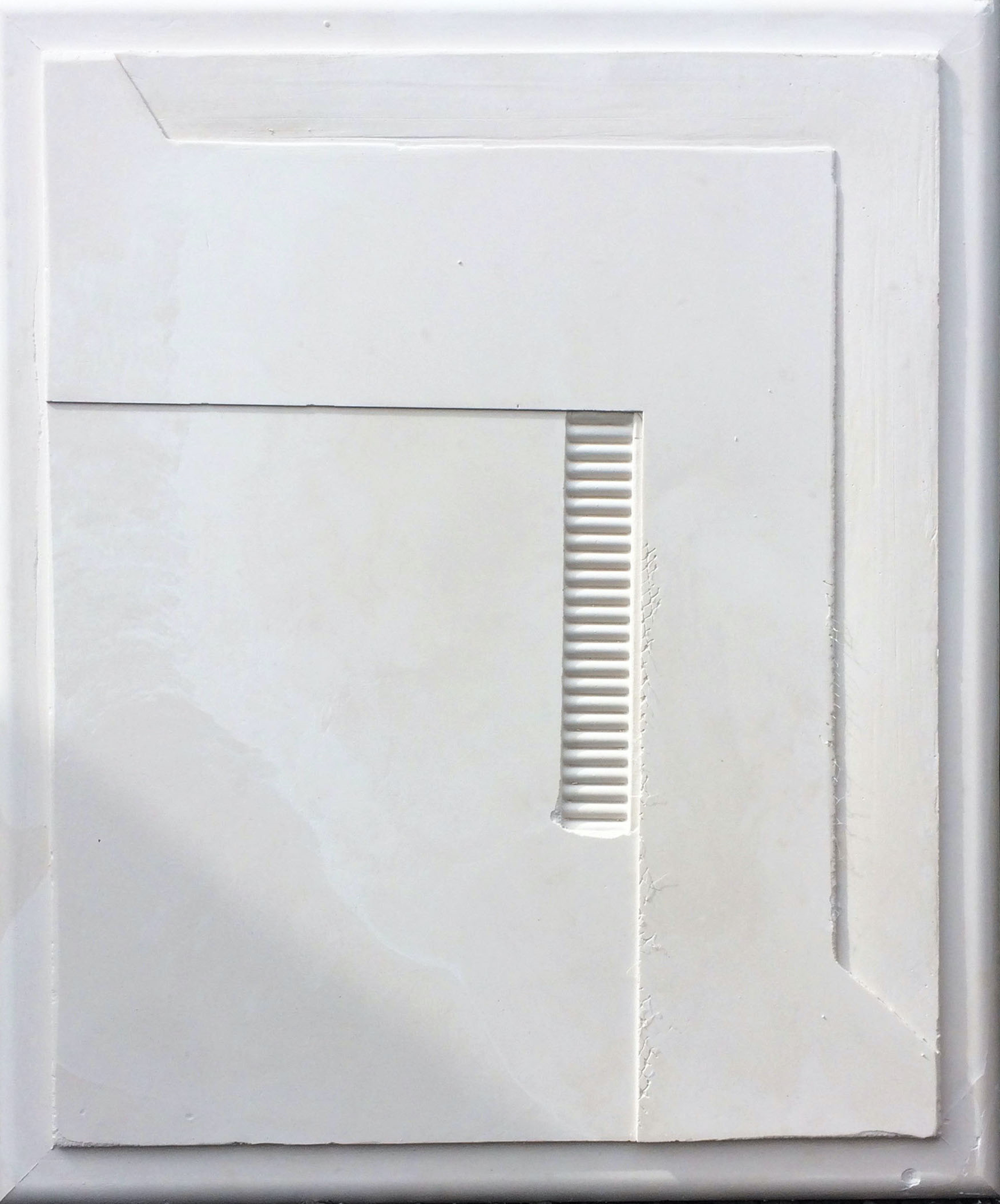

In the past, I've made a series of plaster casts as part of a site-specific public art project on the coast of Dublin, in which I used seawater in the casting process to physically embed the site in the work. This caused an efflorescence or marbling effect on the surface of the cast because the salt migrated to the surface of the objects, and this effect was temporary.

I really liked the process of making work that presented a transient image of itself. Something had been captured but would soon fade away. I think there's an intimacy to seeing something so entropic. For a long time, I've been interested in the paradoxes presented by the sea, comparing its art historical relationship with ideas of expansiveness and sublimity to associations with intimacy and reflection and distance and solitude.

I also have a longstanding interest in the relationship between bodies of water and lines. While navigating across water we imagine latitudes and longitudes, and they provide an imaginary structure across what's essentially an extremely mobile space. Such lines emphasize another paradox of the sea, which is that it's defined by the contradiction of constant change. More recently, the horizon line has been a focal point in much of my research. That's a place of invisibility and of beginnings and endings, and it's this site on the brink. It's a threshold that can never be crossed because it's continuously repositioned in correspondence to the body.

The mobility of the horizon line establishes the eye as the world’s pivot point. Everything reshuffles and shifts around it, offering this new distinct set of geographical facts for every encounter. I'm also really interested in the horizontal, more generally. The horizontal plane is analogous with endings. The ground is literally built of deposits and byproducts. It's a sedimentary relic of long dead creatures and ancient remnants of compressed plants. Things fall down and they're rearranged into new figurations of themselves. The X-axis of the world is this great reorganizer.