Watch the videocast

Listen to the podcast

Read the transcript, presented alongside Sam Durant’s works

Evrim Oralkan: Sam, thanks for joining us. First of all, I want to ask you how have been your past three years in Berlin? How is your new life going?

Sam Durant: It’s great to live in a new country, you know, and have the experience of learning a new culture, a new language, new systems, all of that.

EO: And how has it been for you during the pandemic, in order to integrate into the culture?

SD: It’s just made it—unfortunately, it makes it a lot slower, of course. You know, you’re so limited—we are all so limited about what we can do, how we can meet people. And I think the social factor is really difficult. It’s hard for all of us, right?

EO: Absolutely. Sam, neither a monument, nor the idea and the political power that it stands for, lasts forever. As the artwork behind you also says, another world is always possible, and it is us, the people, who can make a change. Do you think art can have a social impact, a concrete social impact? What’s the value and role of art at this very moment that we’re going through?

SD: It’s people, I believe, that change society, right? So art, I don’t think, makes material changes or social changes, but it helps individuals to change. And those individuals hopefully then can change social relations for the better.

EO: How do you view censorship? The current state of censorship in society and social media—for arts, for culture—how do you look at it?

SD: Well, censorship is a problem, for sure. As artists, especially, to be as free and as open and, in a sense, not to worry about rules and conventions and, you know… Artists have traditionally been transgressive, right? We want to break the rules. So censorship is always—we’re always in a struggle. People who previously really had no voice in society, or very little voice, now have a voice. And there are many people that have been aggrieved and repressed and oppressed, and those people now have a voice. And they’re pissed off. So, we’re hearing from them. And I think that grievance or that complaint or whatever you want to call it is valid.

EO: But what if the censorship is coming from these newly created social media companies that are probably being controlled by social… certain structures, intelligence or otherwise? I feel like we’re at a moment where we’re experiencing this quite a lot.

SD: That’s a question for us: do we want to have social media in private ownership? Maybe it’s not such a good idea. In China and countries like China, of course, it’s controlled by the state. And, you know, I think we can see pretty clearly that that’s not a good situation either. So, we have a lot of work to do to figure out how to make this more equitable, more fair, and to work better for all of us.

EO: I want to talk about your Iconoclasm project from 2018. It’s a series of large-scale graphite drawings which depict some of the historical moments of destruction of monuments. The project was made in the wake of your personal experience of the removal of your public sculpture. Can you tell me more about the Iconoclasm project?

SD: Yeah, I mean, I was really interested in understanding, in a much deeper and broader way, why symbols, why statues and monuments and political and social and cultural symbols evoke such strong emotions—emotions that, you know, lead us to actually destroy the symbols themselves, as my sculpture was taken down because it upset so deeply a group of Native Americans, the Dakota in Minneapolis. And I wanted to really try and understand that. I was very influenced and helped quite a bit by David Freedberg, who is a South African art historian, but based in New York, who wrote a book called The Power of Images. This was a real kind of eye-opener for me to understand this really long history, particularly in [the] religious and cultural realm, of our impulse, our human impulse to destroy the things that make us angry, that remind us of something we don’t want to know, or we don’t agree with. And so I just began this process of kind of researching interesting or important examples of statues and monuments that had been torn down across history—so a very wide scope. So, it was really trying to show a very broad reach, the sort of global scope of it, and also this long historical trajectory, and to try and open it and just have this kind of opening for conversation about it.

EO: It seems like the project naturally ties into your recent exhibition, Proposal for Non-Aligned Monuments, Free Movement, at CC Strombeek, which is also digitally presented on Collecteurs. As part of the exhibition, Collecteurs is presenting the entirety of the video work Trope, which was created in 2020, I think. It slows down and also reverses the collapse of the monuments, kind of for a reflective experience for the audience to process this wreckage of public symbols. Can you tell me more about the exhibition, Proposal for Non-Aligned Monuments, Free Movement?

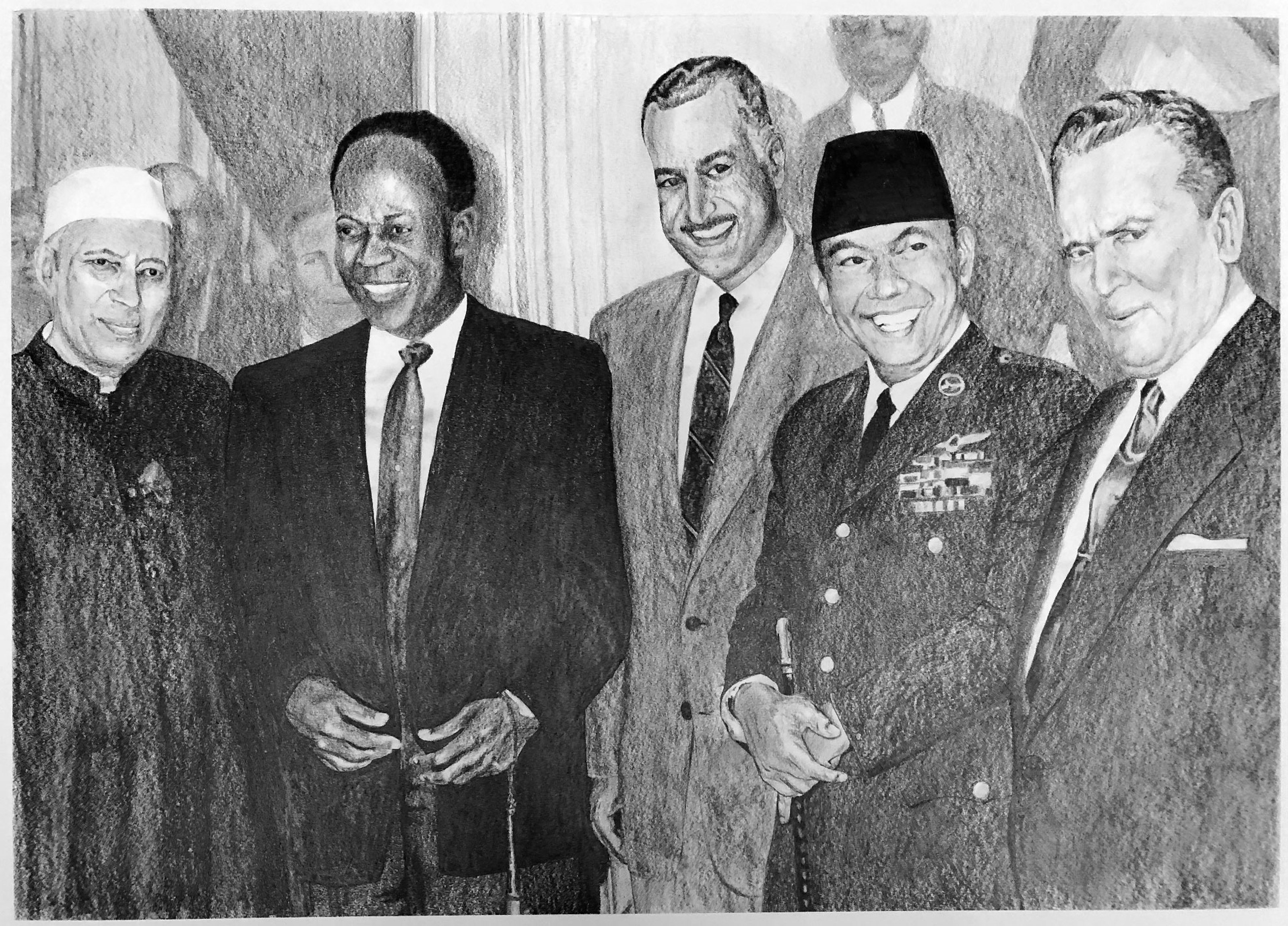

SD: Well, the video was a continuation of my interest in the iconoclasms, and since so many of the recent ones, you know—I guess the oldest ones depicted are from the ’40s, up to the present day. Many of these moments of taking down statues were captured on film, and I thought it was quite fascinating because with film, you have the possibility of slowing it down and changing the context and also reversing it. So, there’s this sense of a cycle that repeats itself, right? We take down old ones, we put up new ones, those, as you said before, you know… We go through this cycle. And that was really kind of, again, trying to open a space for thinking about this, you know, that history’s long, and we change our minds. And the project at CC Strombeek that you mentioned, The Proposal for Non-Aligned Monuments, Free Movement, of course, is connected to my interest in monuments. And these are monuments that are in the countries, in the five countries which were the five originating countries of the Non-Aligned Movement. And the Non-Aligned Movement was, you know, it still exists. It was a kind of utopian project begun in the mid-century, after the end of the Second World War, as a third way, an alternative to the Soviet or the American capitalist model. So, trying to give countries—many of them, or most of them, all of them, I should say, newly decolonized, newly independent countries after the Second World War—give them a way of being non-aligned. So, it was very much about trying to have peacebuilding, economic development, and so forth because, of course, in the early ’60s, the nuclear arms race was reaching really frightening, terrifying proportions.

EO: So, the exhibition, in general, continues to explore your interest in monuments and memorials, which began a long time ago. I see the first project, Proposal for Monument at Altamont Raceway in 1999, it continued with the Proposal for White and Indian Dead Monument Transpositions in 2005, and Proposal for Public Fountain in 2015. So, this is not a new thing; obviously, there has been over a 20-year period of interest in this subject. So, I find it fascinating, you know, the exhibition is very, very interesting—especially the timeline presented, it’s really, really amazing. But it’s also… I wanted to bring up the last Proposal for Public Fountain was in 2015, the last of the series there. And in 2017, your most controversial public sculpture, Scaffold, was itself protested and ceremonially buried by members of the Dakota people at the Walker Art Center. What most of the public did not know is that Scaffold was actually made in 2012 for dOCUMENTA (13), where it was shown without an incident or without any issues. The Walker referred to, and still does, to this as the Sam Durant scandal or controversy in their press releases, and the art media also mimics this. Is it the duty of the artist to do this outreach or the institution’s—especially if the work is not newly commissioned, it is an existing work?

SD: The one, the example that the Dakota protested was included in the structure because it was the largest mass execution in U.S. history. So, it was a combination of all these very significant executions in U.S. history, and that’s why it was there. [As] artists, we have a responsibility. We’re citizens; we’re not children with no responsibility. You know, part of what we do is to transgress norms and, you know, and break rules. So, this is kind of tension, always, for artists. Like, you know, we want to be responsible, we want to be careful, but we also want to have the freedom to bring up new things and break rules and so forth. So, it’s a tricky thing. The institution, the museum, the collecting institution has the responsibility to prepare its audience for the work that it shows. So that’s, you know, at the end of the day, it’s the institution’s responsibility to prepare the community. If they think it’s going to be controversial or difficult, they’ve got to go out and meet those folks in the community, connect to them and talk to them and bring them in before they show the work. Unfortunately, the Walker didn’t do that. Now, I mean, you know, had I been commissioned by the Walker to make a new work for the site there in Minneapolis, I never would’ve done Scaffold, of course. And I would have gone and met with everyone in the community and done that, as I have for every commissioned work, new work in any community or place where I do it. I always do that. So, as you said, the Scaffold was a piece that was older and was purchased and brought to a new site, a new context. And, you know, I, having some knowledge of Minnesota and the large Native American community there, I felt bad that I didn’t, you know, think, “Oh, we should maybe meet beforehand.” And, you know, and that’s what I apologized for. I apologized to the Dakota because, you know, of all people, I should have been someone who knew to do that. And I apologized for that oversight on my part. So, you know, I’ve tried to take as much responsibility as I can for the situation. That said, I think the ultimate—and I think everyone agrees—the ultimate responsibility is with the institution. I mean, you know, just in a sense of capacity, of course an institution is a big… I mean, everybody’s working hard; they’re overworked, of course. We know that—underpaid, overworked, all cultural institutions suffer from this. But that said, there is an infrastructure there, and one of the jobs of the institution is to maintain a connection with its audience. An artist is one person, and I don’t have a big infrastructure. I’m just one guy, you know? So, it’s hard for me, and that’s true for any artist. I don’t say that about me; I’m not special in that way at all. Every artist is this way.

EO: I’m excited about seeing your new public artwork, the drone, in New York. I think it’s going to be installed in May, at the High Line. Is that true?

SD: Correct, yeah. Should be the end of May, beginning of June.

EO: Great, okay. I hear that the work is like kinetic artwork and a replica of the Predator drone that the American military uses. Can you tell us a little bit more about the work and how it’s going to function and what you were aiming at?

SD: You know, when the drone program—the targeted killing, assassination program—was being developed by the Bush administration and then really greatly expanded under the Obama administration, it was just shocking to me that the U.S. government was going and killing people in faraway countries that we weren’t at war with, and doing it in a way that, you know, seemed very inhumane. I mean, as if war could ever be humane, but this seemed particularly problematic because it was being done all remotely with cameras and surveillance. So, I thought, “Man, we need to have a conversation about this. We need to be aware of this in the U.S.” And so the idea was to make this, a symbol of this program, visible in America. Of course, I’m very interested in the intersection of art and war and, you know, particularly the early 20th century, where so many European artists were having to deal with the First World War and the Second World War. How did that affect them? How did that affect their artistic production and so forth? And one of the important people for me, personally, because I’m a sculptor, is Constantin Brâncuși and his Bird in Space, of course. And so I thought I saw this maybe interesting analogy between a modernist sculpture and this drone plane. So that kind of formally gave me a structure to think about putting this drone on top of a pole and having a base where people could sit on and stand around and look at it. And then the idea of it being a wind vane so it rotates in the wind, you know, sort of, in a sense, giving the viewer the idea of getting your bearings, getting your perspective, knowing where you are, what the direct, you know… And, of course, the cliché of, you know, the Bob Dylan song, “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows”—that kind of idea of a moral compass, as it were, as well. So, bringing all these kinds of ideas together, this was the concept in the work.

EO: Beautifully put, thank you. I’m really looking forward to seeing that. I think that’s going to be a part of my daily commute when I’m dropping my younger son to school, so I’m excited about that. But thanks, Sam. Thanks for joining. I really enjoyed this, and I’m glad we got to clarify some of the things that the public needed to know. So, thank you very much, again.

SD: Thank you. It was my pleasure.