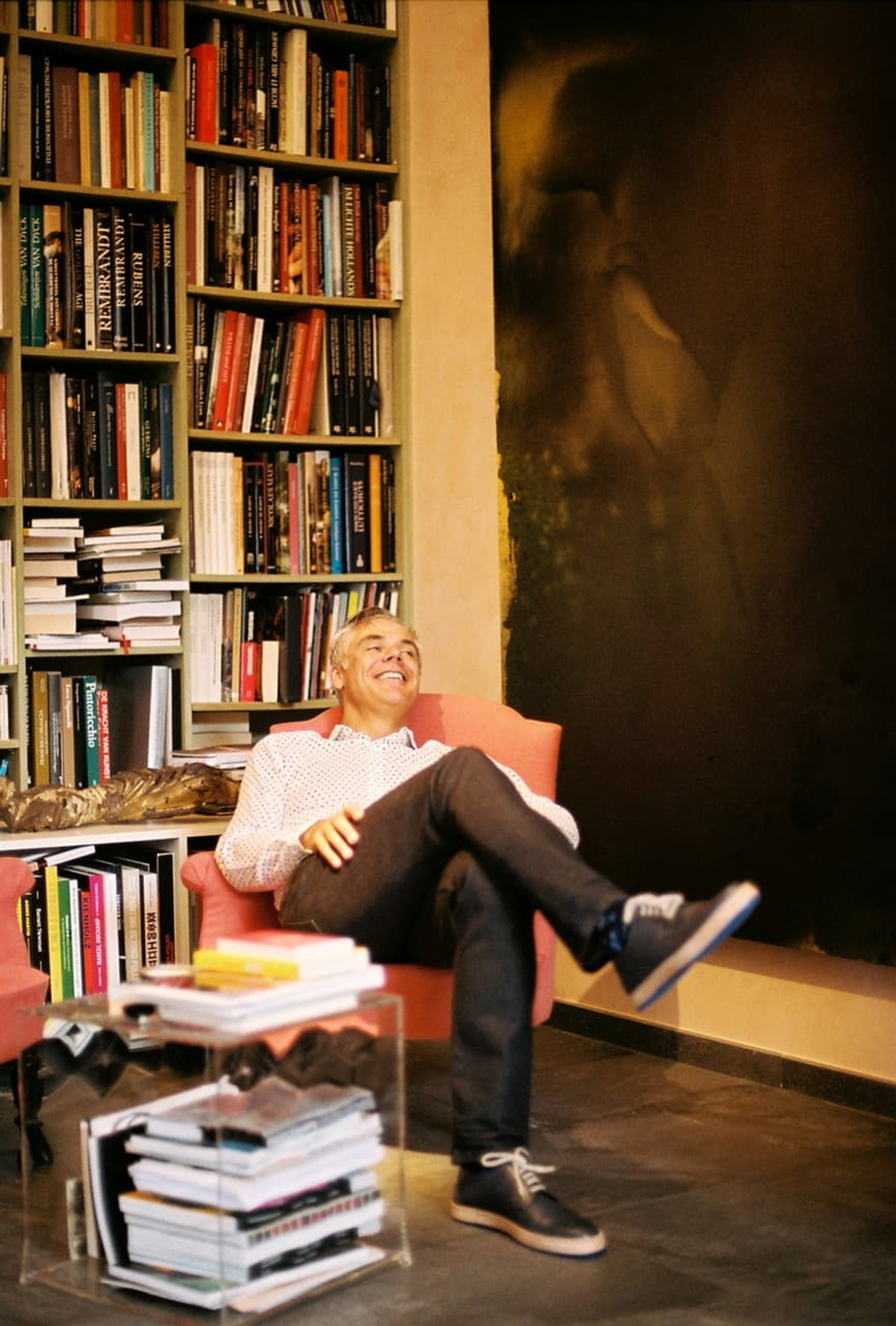

Like invisibly moving tectonic plates, the trends, truths and contents of the art world are in constant and quiet transformation. It is up to collectors to navigate this ground. Brussels-based private collector, CEO of the Belgian National Orchestra, and Professor of Sociology at Ghent University, HANS WAEGE, talks to Collecteurs about overcrowded art fairs, the role of digital in the art experience, and a collector’s self-expression.

Collecteurs: How does collecting contemporary art creatively inspire your positions at the Belgian National Orchestra and as a Professor at Ghent University?

Hans Waege: For me, collecting contemporary art is about looking differently at the world around us, about being in contact with different sensitivities and different ways of expressing meaning. Art is, in many ways, about exposing second and third layers of meaning. It’s also about meeting the artists and other collectors. But above all, it’s about aesthetics. I think aesthetics is an essential part of civilization and a need of the human kind to transform from destructive capabilities. It’s also an engine for moral progression. The aesthetic sublimation of strong emotions and adding aesthetics to reality are ways of advancing morally.

I typically focus on abstract art because of its aesthetics and its more obvious connection with abstraction in “art music,” most of it being symphonic music.

This aesthetic journey is an essential part of my life – both at work and personally, for my individual development.

Collecteurs: We’re interested in your definition of aesthetics. Beauty—its presence as well as its absence—is an ever-abiding segment within our daily lives, and almost always the initial catalyst of why something invites our attention. Isn’t it somewhat impossible for a work to be just beautiful, or just ugly? Lately, there seems to be a trend within contemporary art—referencing mostly post-internet art here—that somehow thrives on aesthetic meaning; devoid of anything else. Can beauty ever be truly meaningless? Additionally, we’d be interested in your thoughts on post-internet art as a literary collector who has personally witnessed several shifts within the art landscape.

HW: First of all, I don’t define aesthetics as beauty or ugliness. These terms are too close to what we consider fashionable, and too close to the subject matter or the material being represented. For example, we don’t like renaissance furniture because we are living in a neo-minimalistic age where we consider copying old modernist furniture as a highly aesthetic statement and a 17th century tortoise shell cabinet is a thing of questionable taste or something that belongs in a museum. The same goes for art defined as art. We don’t like pre-impressionist landscape, and so on. Almost twenty years ago, you could buy paintings from the Zero-movement for close to nothing. Now an early Günther Uecker is over a million euros. In the end, many of these statements are made based on ignorance and incomprehension.

It all starts with a sense of composition of the elements of a work and the work in context. It is a debate with the rules of classicism. You simply cannot escape from it. You can ignore it and you can break the rules, but in the end you will have achieved a position in this world. We consider Pollock a great artist, because in the end it boils down to colors and construct. These are the basic categories of classic art. Of course he did something new, or at least it seemed that nobody did it before him… or they hadn’t met Mrs. Guggenheim. This all counts, even in the career of a great artist. Becoming great is, above all, a matter of choice, not just a matter of talent.

What we call “ugly” is an essential part of the tensions represented in art. We will always consider shit as ugly, but from Bruegel and Manzoni all the way up to Wim Delvoye we’re exposed to ugly shit as art. Gothic art is also full of ugliness. Herbert Zangs – who many people don’t know – is a very good artist because he understands material and composition, even in his most extreme Arte Povera works. He is not an exceptional artist because he was out of control and socially unadapted in many ways, but because a substantial part of his work is more interesting than other much more expensive works that came out of the Zero-movement.

But to answer your question: no, beauty is never meaningless, but nothing is meaningless. Silence is very meaningful. Meaning is very context dependent and is always an interaction. Once you escape a theoretical void, ‘whatever’ becomes loaded with some meaning, even the void. But again, beauty is fashionable. Look at Rubens, the classical beauty of his early career is how we have come to define something as a having Flemish Baroque sense of beauty. This is very far from Raphael’s classicism or Caravaggio’s extreme sense of beauty even when presenting ugliness.

In addition, portraits depicting young people are typically more expensive than often more meaningful portraits of older people. Of course, not when we are talking about Rembrandt, but in that case you aren’t buying a painting, you are buying a brand.

I will touch very briefly on your question on post-internet art. I think we are at the beginning of internet art. However, the “post” is very interesting. The 21st century will be where the lines between human and machine will be crossed in previously unseen ways. This, together with an augmented, blockchain-informed and 3D way of connectedness will lead to a new definition of the human. If art is, as I believe, both a mirror and a representation of the human, the position of the arts and the art world is about to change in its entirety. The use of algorithms written by humans to produce visuals will be a minor detail of a whole new era to come.

Collecteurs: It will be interesting to see how the entirety of the art world will shift accordingly. Are you excited to experience these upcoming changes? I wonder if the moralization and ideologization of art will completely cease to exist, whether one day it might exist in absolute purity, and whether we would actually appreciate its new state of being. If art will no longer be a place for ethical debates.

HW: As long as art is produced by humans, it occupies a position in the field of ethics and morals.

I think it’s highly relevant that art has a position in this field. Parts of the art world try to define art as devoid of ethics and morals, and instead link it only to materials or sensorial experiences. However, once you enter the field of aesthetics with your sensory art, you are also dealing with ethics and morals. The Greek civilization was built on aesthetic ideals and we are still rooted in this tradition. One could say that, ultimately, it is impossible not to discuss ethics and morals. Moreover, absolute purity is often a goal of a moralistic ideal so, in this sense, your proposition for absolute purity of art is moral at its extreme.

Collecteurs: What does it mean for aesthetics to be the engine for human morality? Is it because, historically speaking, we have killed because of it?

HW: We killed for whatever reason. We killed for love, for possessions, for power, wealth and jealousy. We also killed for racial purity and even for fun.

For me, aesthetics is based on choice and reasoning, it has to do with idealism and humanizing the world around us. Art and science are the main carriers of civilization. For instance, when you listen to the Psalms of Orlando di Lasso you have to believe that mankind is capable of great, unknown things that lead to a more humane, respectful and civilized world; that there is something better coming. It is an extreme sense of perfection. Art is about more than what is represented. When Beethoven was writing, it led to his late String Quartets and his 9th Symphony. A sense of humanization, a heaven of logic, understanding, brotherhood and, of course, innovation. In a way, the streetfighter Caravaggio dreams of a better world in many of his paintings. There’s a little bit of the Holy Virgin in everybody.

When this success is shared with many people over a long period of time, it shows signs of great art. The power of art to re-emerge after a substantial period of time is often a sign of its sublime quality. That is what a humanizing world universally looks for. Dehumanization is the opposite. A dehumanizing world converts art into ideological slaves by selecting the right art from the past or by a narcissistic interest in its own lifeworld. Diversity, discovery, re-discovery and tolerance are its opposites.

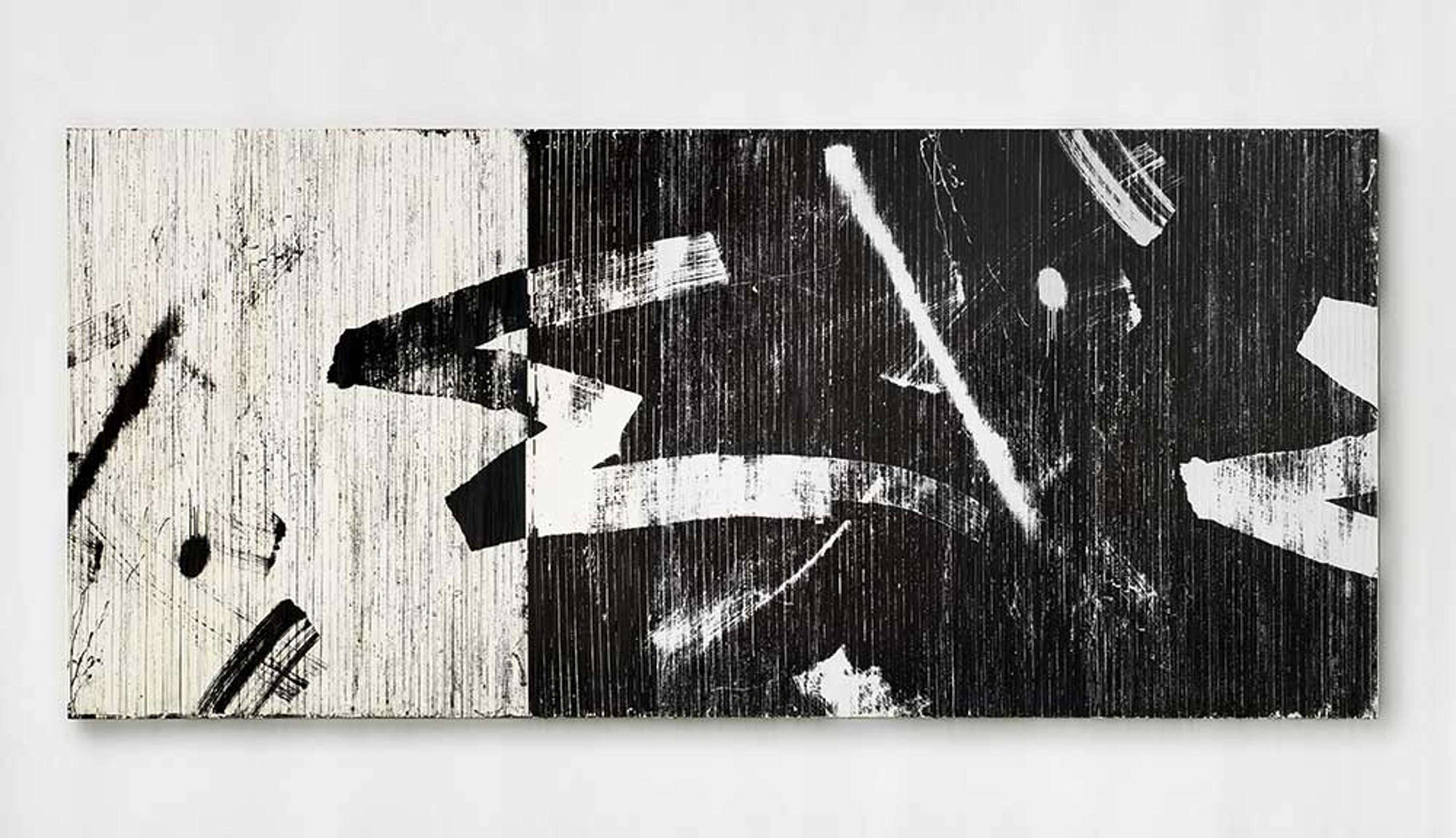

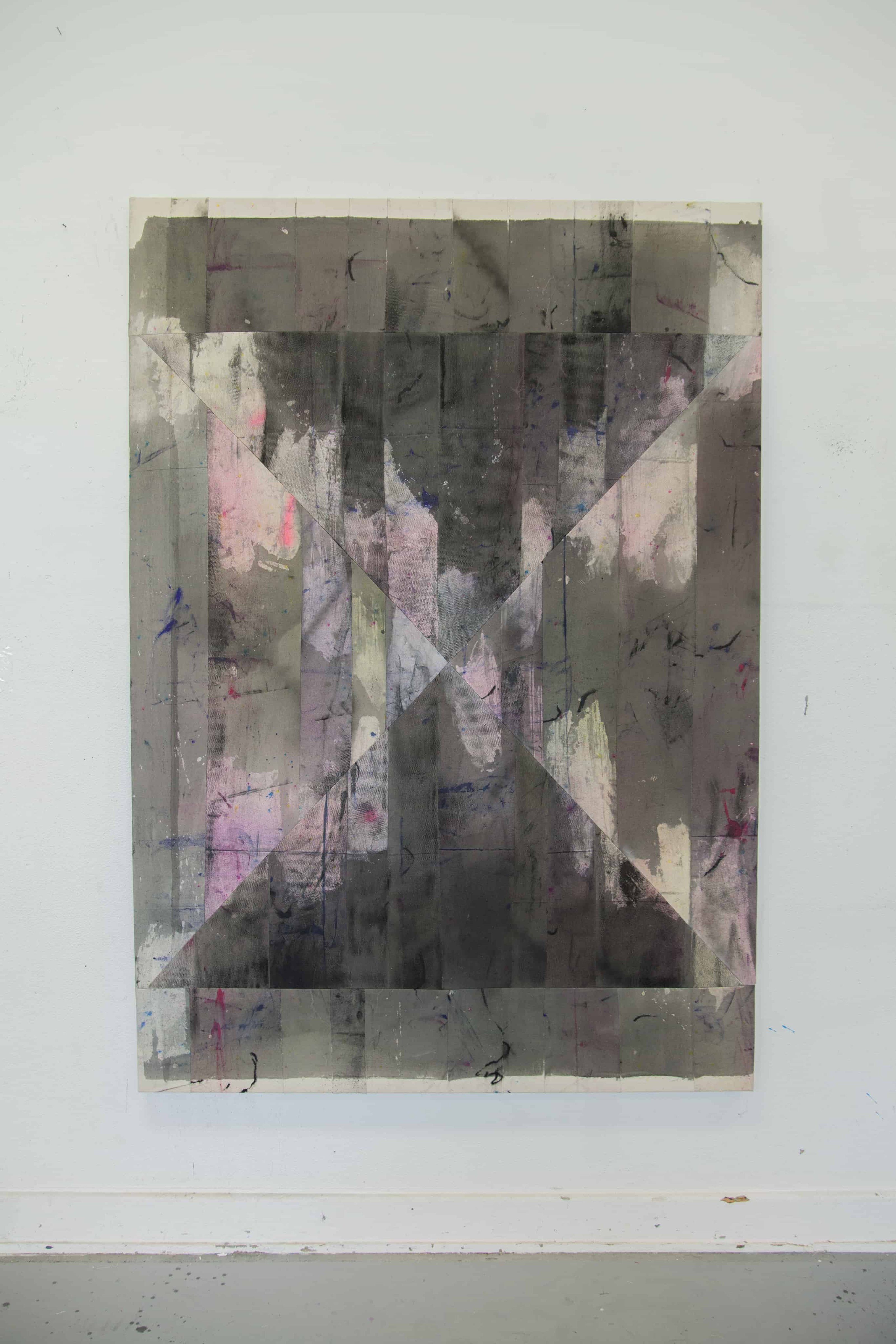

Gregor Hildebrandt

Collecteurs: What happens when art is turned into ideological slaves? Could you give an example with an artist or a particular piece you’re thinking about? In a way, universality sounds very ideological, and one-sided.

HW: Of course, universality is ideological; it is essentially an ethical position. “Alle Menschen werden Brüder” (All Men Will Become Brothers) means respectfully co-existing with all of our differences. It is an open ideology, not a closed one. When I refer to Beethoven, it isn’t by accident. He always broke away from conventionalities, which doesn’t mean that he was destructive. His universality is open and multiple. Of course, it’s about craftsmanship, excellence, concentration, diversity and development. It’s everything but frivolity.

Art, very often, has been used in an ideological manner. Shostakovich’s entire life was a battle and compromise with ideology. Yet how many artists are fighting – let alone winning – the battle with the extreme commodification of the commercial art world? Karl Marx is still very relevant, probably even more than ever, when talking about the alienation of the true meaning of artistic production. The same goes for nationalistic attempts to capture the arts.

To conclude: art is part of society. One shouldn’t expect salvation or a supernatural force from the arts as a whole. Just like any other functional part of society, art is, above all, subjected to the human condition which is composed of trials, mistakes, some very good and a few extraordinary results.

Collecteurs: Does successful art necessarily demand to be meaningful?

HW: It depends on how you define success. If you define success by being expensive, then it doesn’t need to be very meaningful. It needs to be easy to understand, easy to recognize, usually colorful or, especially today, white monochrome. And let’s not forget, it needs the support of an important, financially strong gallery. Money is required to build and sustain the market of an artist.

Meaningful can refer to different aspects of art: art theory, research, innovation of technique, and means of material artistic expression, together with the latter, the decorative aspects of art, developing traditionalism and cultural identity, politics, religion and spirituality in general, social observation, finance, … So I guess, in the end, art is meaningful in at least one or more of these “fields of meaning.” And meaningful has to be seen as the result of a function that includes both substantial time and space dependent variables.

We have to define success by achieving a coherent artistic œuvre, of building a repertoire that is objectifiable with a personal language, founded in a strong sense of observation and a reflective sense of representation in order to engender something that transcends the represented material object. In the end, you should see a well-considered artistic lifeworld, a technical essence, a language that is specific, identifiable and coherent. That’s when we will get close to meaningfulness. So all this is meaningful art.

To be great, meaningful art is a very different question. We haven’t gotten much further than the idea that it has to transcend time and space at some point and remain there for a certain amount of time, at that level of objectivation of excellence. The rediscovery of masters is one of these exciting moments when scholars have successfully made art re-enter the walhalla of the art world. Artistic judgment is a result of many pitfalls and mistakes. Medieval Gothic art has gone out of style and back in many times over the past few centuries. The destruction of art due to matters of taste and style, religion, ideology and politics has left us with a relatively distorted view of our artistic inheritance.

I do agree with the basic idea of Liam Gillick’s that artifacts, objects and, thus, also art, carry meaning independent of the relational context that they are part of – but this is a highly theoretical discussion. What it means is that very meaningful art can be very unsuccessful at certain times, and that very successful art can be close to meaningless in any future path of mankind that is reflected in the arts. But it could become very meaningful to a history museum, as part of a collective memory, or just as decoration. A substantial part of ancient art is limited to these constructs of meaning. It is very important because mankind, in the end, always needs identity and identity needs roots.

Collecteurs: How do you see the evolution of collecting? Where will it go from here?

HW: Since we have history and philosophy-based civilizations, there have always been collectors and there will always be collectors. But we will not always be collecting contemporary art in a massive way. It’s very much ‘today’ and it’s very human to think that this trend will go on forever. History reminds us that older art will make a reentry at some point in time and that the contemporary will struggle. The period that contemporary art was struggling lie not far behind us. Before Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst or Jonathan Meese, contemporary art was the little brother in the art world; now it’s omnipresent.

Collecteurs: Do you think exhibitions will transition online in the future? If yes, what specifics do you see?

HW: In the near future, online will grow in its existence alongside physical exhibitions. More and more new art forms will specifically address this virtual space. However, most art that is being produced today, let alone everything from before, is still impossible to reproduce properly on a two-dimensional screen. I never saw a reproduction of Rubens’ The Descent from the Cross that was capable of giving even two percent of the experience in-person. I am very often disappointed when I see in reality an artwork that I first saw photographed, and vice versa. Instagram is even worse, but I like it a lot for other reasons.

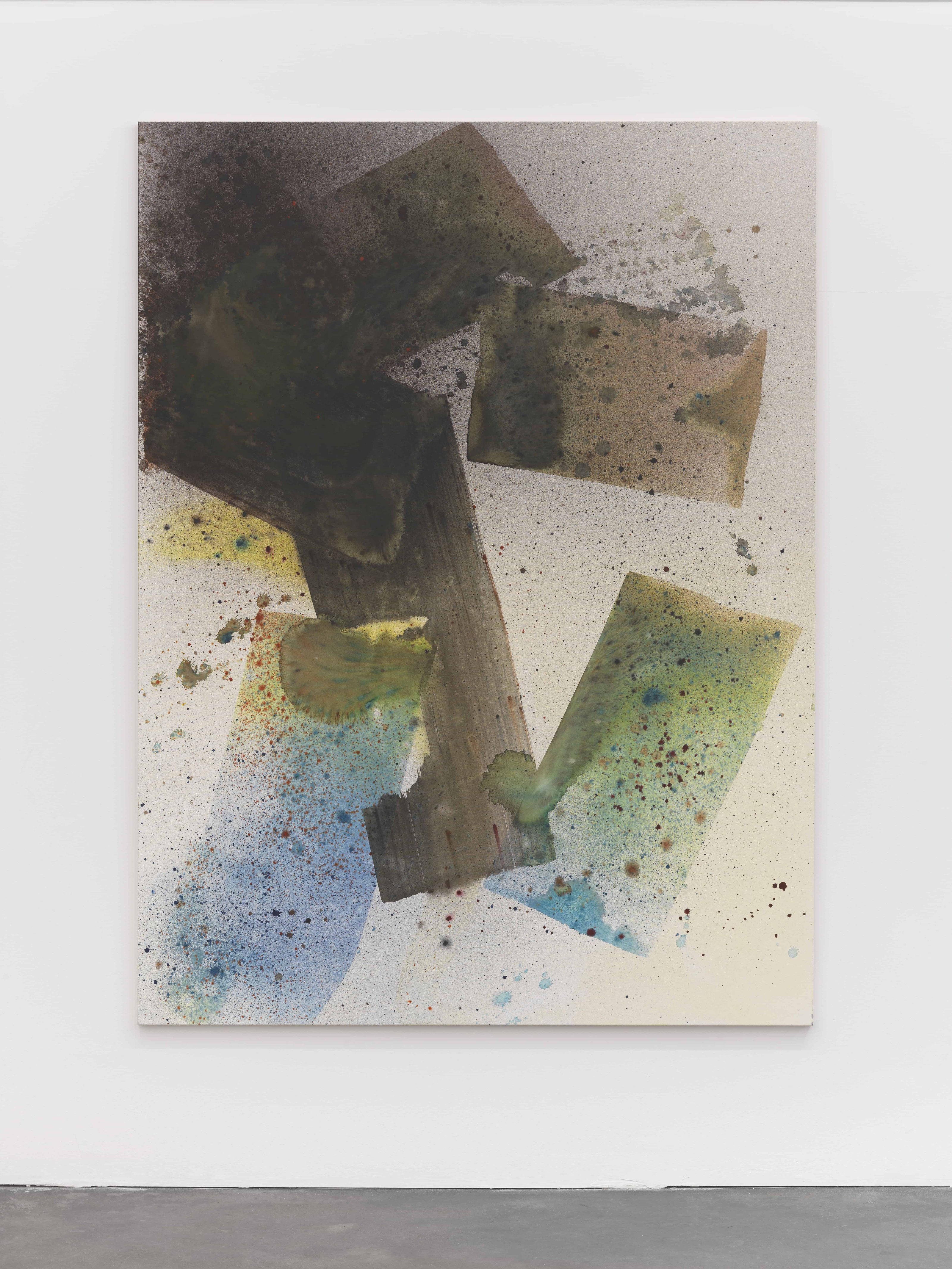

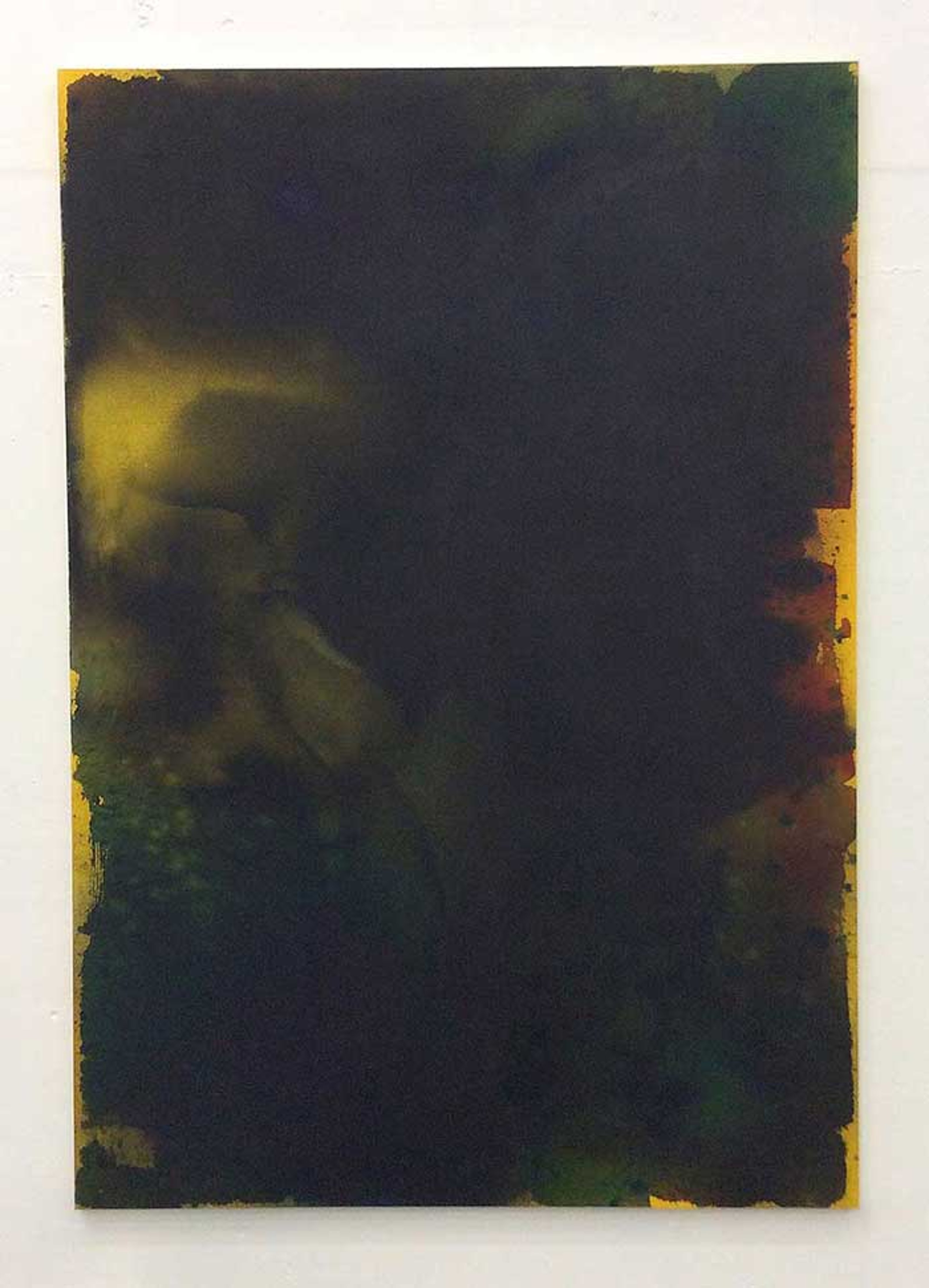

Several great artists have proven first-hand that their art changes in relation to the space in which it’s shown. The physical experience of art is still essential. Can you really understand a work by Carl Andre, Günther Uecker or Sterling Ruby through your screen?

The online world can be very useful, but the art has to survive confrontation in the physical space. The internet is essential in transmitting information, making our first selections and discovering art, but we need real spaces to experience it.

The same goes for art fairs. Most of the time, I really don’t get a clear understanding of an artist’s work at fairs. Of course, just like there is “Instagram art” today, there is also “commercial fair art.” It is impossible to profoundly consider poetic and lifeworld-creating artists like Gregor Hildebrandt or Laure Prouvost at a fair, let alone on Instagram. Their work needs a more precise and intimate approach. It belongs in specific spaces and becomes more meaningful through interaction with the space, just like Carl Andre and many other great artists.

Collecteurs: Would you ever open your collection to the public eye? What would the motivations be for doing so?

HW: In the physical sense, probably not. I like sharing my passion with friends. I do like to show art I have in my collection in the virtual space though, because I want to defend an aesthetic or, more specifically, an artist. And if there is a question of loaning works for exhibitions, I am very willing to do so.

In that sense, I highly respect those wealthy collectors that show their collection in a museum or temporary exhibitions. That is real sharing because no museum entrance fee can ever repay the money invested in the art itself. There is some self-representation in it, but at some point we are all actors in the everyday theatre of life. In that sense, these collections – and also my own collection – are a way of expressing yourself, to yourself and to your significant others. My significant others in my role as an art collector are, above all, friends. I feel collecting is an art and not art itself, of course.

Collecteurs: What are some of the outdated practices by players in the art world? Any ideas on how to change them?

HW: When things are outdated, they usually cease to exist sooner or later. I do think that there are far too many contemporary art galleries and, likewise, far too many contemporary artists. Actually, there is simply too much uninteresting contemporary art around.

At a certain point I hope, little-by-little, people will realize that on many occasions they paid a lot of money for uninteresting stuff. I don’t know when, but the real and informed collectors will remain in the market for a long time, and the rest will vanish. Look at the world of ancient art and antiquities: few dealers and collectors survived and hardly any new ones are appearing. It’s just not fashionable anymore, and during the high times of ancient art and antiquities, a large amount of mediocre, bad and forged works of art were sold for enormous prices. When this happens, trust is damaged.

So it’s not about outdated practices for me, it’s about history repeating itself. The boom of contemporary art will end, as will the ridiculous price tags and the overcrowded art fair and art gallery circuits. Most selections for art fairs are artificial. In the end, a fair is an economic reality, so you need to sell enough space to galleries to survive. In addition, there aren’t enough truly intelligent, independent, and highly knowledgeable curators to take care of all these fairs.

Honestly, I am afraid that we are close to a tipping point. The new Art Basel fair Art Düsseldorf and the discussion in Berlin over Art Cologne’s possible expansion is just one indication of the fact that the system is overheating. Frieze New York will follow these and they are preceded by Miart and Independent Brussels. This will lead to a correction or even a temporary collapse but, for the latter to happen, it will take several more factors to coincide but a collapse of the secondary market for young art is one of the ingredients.

Collecteurs: How have your interests changed over time? What do you do when a work or object no longer fits your collection?

HW: My interests did change. After collecting Gothic and Renaissance for 25 years, I wanted a new challenge. I always study and dig deep into what I collect. I am selling part of that historical collection because I know the periods’ sculpture very well and I am not rich enough to keep everything and to do something new properly, at the same time. I have kept a selection of the collection, because I still like it a lot and for sentimental reasons.

I do not sell contemporary art of emerging artists, I store it.

Collecteurs: What does it mean to be a collector in the 21st century?

HW: We are living in a period of abundant art production and very few of the approaches in abstract or figurative art seem to be ‘new.’ I stress seem because the huge amount of information on worldwide art production and recent art historical production makes it quite complicated to see clearly. I’ll come to that later. But the most important criteria are probably being genuine, being unseen, and showing personality; these are important to me. By ‘unseen’ I mean not too close to the citation of work or artists of earlier times.

Art has always moved fast around the globe but now we are talking about going worldwide in seconds. That makes a difference, but I don’t feel like it’s a problem. On the contrary, I think it’s very exciting. But many collectors who collect themselves probably look, most of the time, to art that connects to their roots. The same goes for great art — it often connects to the roots and personal experiences of the artist.

The art market is extremely commercial today: over 300 fairs and an explosion of gallery spaces that only recently seemed to cool down a bit. The price levels of emerging art are relatively high for European standards; the focus on fairs is part of the cause. It’s difficult to justify a price tag of over 10,000 € for an artist that hasn’t proven anything.

Museums are part of the game too.

Even the distinguished museums present contemporary art of the ‘New Now’ type. I often don’t get a clear, logical understanding of the ‘why’ of the selection, and the “curators” cannot explain the selection in an objective way. I usually just ignore it, but sometimes I encounter interesting art at an art fair or in a magazine. I trust the taste and selection of some curators, which is not the same as blindly following them. For someone interested in emerging artists, these selections often come at a later point in one’s career. Some practices are fundamentally problematic: the gallery-sponsored museum shows, usually in small or medium-sized museums; the sometimes unhealthy personal relationships of curators with artists or the galleries. A good museum curator doesn’t advise collectors, doesn’t go to gallery dinners, and they themselves and their family are not collecting.

Another issue for collecting today is that disruptive ‘schools’ and movements seem to be largely out of fashion. Postmodernism seems to mean that every approach can exist next to the others. So you are basically dealing with the challenge of overexposure and no clear selection based on distinct “artist movements”. This is not helping the collector.

Price also seems to be a bad indicator. I see noticeable mediocrity, at very high price tags and even with some more established galleries, so these selections are not always trustworthy. Then you get reflections like, ‘Yes, you’re right, this artist doesn’t seem to realize today what they were promising at the beginning. But they are with a great, expensive gallery. Don’t worry, they will take care of it’. I won’t mention some of the names, but have a look at some of the recent or young German minimalist artists. I just ignore it. Galleries don’t take care of quality in the long run, only the artist does. And, like in music, not all artists can properly deal with success at a young age.

Collecting is a tough job if you take it seriously, and deception is a real risk for the individual collector, the artist, and the contemporary art world as a whole. Diversification in a collection is necessary but, on the other hand, you probably want to create focus in your collection or you could end up with a lot of uninteresting art. Finding the right equilibrium is part of the collector’s job.

Collecteurs: Is it important to catalogue collections?

HW: It is crucial! I see young collectors and several mid-range galleries paying no attention at all to this. You need to ask for certificates, keep your bills and document your collection. I myself should do even more about it.

I do insist on getting a signed physical certificate. Some galleries are surprised and they want me to believe that the emailed bill is sufficient. I can tell you by experience: it is not at all. It is a problem for the artistic heritage of the artist and a real threat to the financial value of your collection. I give more and more attention and respect to those galleries that document the works they sell and that keep records. It’s an insurance for the whole œuvre of the artists you are collecting. Look at the damage that has been done to the work of Lucio Fontana, Sigmar Polke, or Herbert Zangs by forgeries. Rebuilding trust in these artists is a tough job. I sometimes fear that even some artists themselves participate in this game once they are old and they try to build their own imaginative heritage. If an 80-year-old artist is releasing massive amounts of unseen, unpublished work of his early career, I am not buying. Herbert Zangs made an artistic statement of this with his act of anti-dating his own work at early age.

Professional galleries, publications and great, well-documented and well-known collections are the best help for achieving trust. Some artists kept superb and honest historical records. The reconstruction of his œuvre is therefore easier. I also don’t blindly trust ‘experts’. Some of them are too severe, others are selectively severe, and some are not really knowledgeable.

The artist and the art world can only survive based on trust. We are all responsible for creating and maintaining this in order to avoid problems. Collecting is a joy but also a responsibility for me. Galleries are the primary institutions charged with taking care of this, for they get paid to do this job. Taking 50 percent of an artwork’s sale price and not doing the cataloguing or certification of an artist properly is highly irresponsible both towards the artist and the collector. Collectors should be more firm on this, including myself.