The Palestinian experience of exile during the period from 1975 to 1986 is a multifaceted tapestry woven with threads of longing and resistance. At its core lies the dichotomy between the tangible memories of those who were forced to leave their homeland by Israel’s military forces and the inherited narratives passed down to subsequent generations. The displacement of Palestinians during this time was not merely a forced physical departure from their land; it was an existential response to the oppressive conditions imposed by occupying forces. For many, leaving Palestine represented a quest for refuge from persecution, a defiant assertion of identity in the face of cultural erasure, and a poignant act of survival amid adversity.

Throughout their diasporic journey, Palestinians grappled with the challenge of preserving their heritage and resisting attempts to delegitimize their indigenous connection to the land. This struggle found expression in various forms, from art and literature to cinema and grassroots activism. The notion of diaspora, far from being a passive state of displacement, emerged as a locus of resistance and cultural resurgence. In the realm of Palestinian art and literature, themes of diaspora and counter-discourse flourished, serving as potent vehicles for reclaiming narratives and asserting agency. Artists and writers crafted narratives of resilience, depicting the indomitable spirit of a people determined to resist cultural assimilation and preserve their identity.

The impact of exile and diaspora during this period varied across different countries and communities. While some Palestinians sought integration into host cultures as a means of escaping the stigma of alienation, others steadfastly clung to their identity, viewing assimilation as a betrayal of their heritage. In essence, the period from 1975 to 1986 represents a chapter in the Palestinian narrative characterized by resilience, resistance, and the relentless pursuit of justice. It is a testament to the enduring spirit of a people whose identity transcends borders.

The output of diasporic Palestinian communities is characterized by their ability to document a past life in their prohibited homeland. Musicians, painters, poets, writers, and filmmakers have relentlessly brought to life the Palestinian experience, highlighting themes of suffering and hope. Palestinian artists dispersed across the globe found themselves confronted with challenges shaped by their cultural identity and their shared experiences as members of a displaced community. As they grappled with the complexities of their existence in the diaspora, several key cultural aspects emerged, each playing a pivotal role in shaping their artistic expression and activism. Art emerged as a powerful tool for preserving culture, resisting the looming threat of cultural erasure, and reclaiming narratives of identity. Embracing innovation and experimentation, diaspora artists boldly pushed artistic boundaries, blending traditional Palestinian art forms with contemporary techniques. This article provides profiles of important artists active from 1975-1986 within the Palestinian diaspora and their varied ways of confronting the subject of identity from the position of exile.

Abed Abdi was born in Haifa. In 1948, he and his family were forced to leave seeking refuge in Lebanon, and later in the refugee camps of Syria. His father, Qasem, remained in Haifa during the armed conflict, and the family was finally able to reunite in Haifa in 1952, by which time the city was under Israeli rule.

Abidi began his career as a blacksmith and later became an illustrator for Arabic publications in Israel. From a young age, Abdi displayed a natural talent for art, drawing inspiration from the vibrant culture and rich history of his homeland. Despite facing numerous obstacles, including limited access to formal art education, Abdi's passion for creativity remained undeterred. In the early 1960s, Abdi traveled to Moscow to pursue his artistic studies at the Surikov Institute of Fine Arts. Immersed in a new environment and exposed to diverse artistic influences, Abdi honed his skills and developed a unique style characterized by bold colors, intricate details, and powerful symbolism.

Upon returning to Palestine, Abdi emerged as a leading figure in the local art scene, using his talent to shed light on the plight of the Palestinian people. His work addressed themes of identity, resistance, and resilience, capturing the struggles and aspirations of his community. His commitment to social activism extended beyond his artwork, as he became actively involved in advocating for Palestinian rights and promoting cultural exchange. He collaborated with fellow artists and activists, participated in international exhibitions, and used his platform to raise awareness about the Palestinian cause on a global scale. He made history as the first Palestinian to create monumental art on native soil. His allegorical monuments in Galilee pay tribute to human resistance, featuring a narrative mural depicting Elijah's defiance and survival, as well as a bronze monument honoring six Palestinians killed during protests on March 30, 1976, a date observed by Palestinians as Land Day.

In his early artistic years, Abdi produced a significant body of graphic works. While still a student, he crafted a series depicting Palestinian villages, land confiscation, and refugee experiences, published in 1973. He further illustrated the first Arabic edition of Emile Habibi's renowned book, "The Secret Life of Saeed: The Pessoptimist," in 1977. Additionally, between 1980 and 1982, Abdi illustrated a series of short stories by Salman Natour under the title "Wa Ma Nasaina" (And We Did Not Forget), published in Al Jadid.

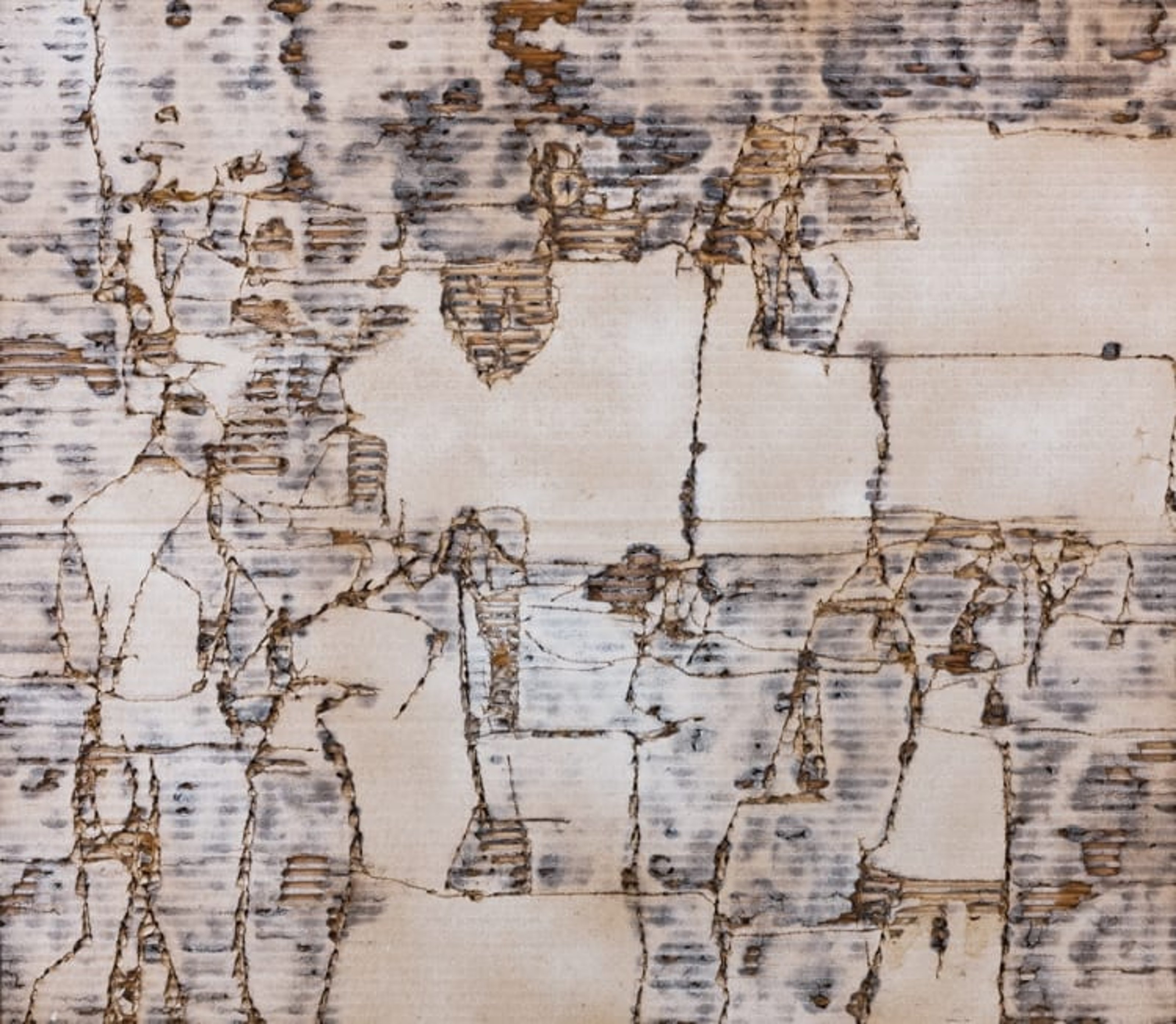

Born to Persian parents in Haifa, Palestine, Maliheh Afnan's artistic journey traverses continents, weaving a tapestry of cultural influences and personal memories. Afnan's oeuvre is a testament to the convergence of diverse cultural landscapes. Her work, often described as relics of an ancient civilization or archaeological excavations of the collective psyche. Her art addresses themes of displacement, exile and memory of place. Afnan received a BA from the American University of Beirut and an MA in Fine Arts from the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design in Washington, D.C. Afnan lived in Kuwait from 1963 to 1966, in Beirut from 1966 to 1974 and in Paris from 1974 until 1997, when she moved to London.

Central to Afnan's artistic lexicon is the delicate art of calligraphy, a motif that permeates her compositions, suggesting the presence of the written word without divulging its explicit meaning. Her works on paper and tablets of painted plaster evoke the aura of ancient texts, bearing traces of human contact and the passage of time like palimpsests awaiting decipherment. Influenced by both Middle Eastern and Western artistic traditions, Afnan's canvases resonate with echoes of Pollock's frenetic energy, Rothko's contemplative depth, Dubuffet's raw expressionism, and Klee's whimsical abstraction. Yet, amidst this diverse array of influences, Afnan's voice remains uniquely her own, a testament to her ability to transcend cultural boundaries and forge a distinct artistic language. Afnan's creative process is a testament to the enigmatic interplay between memory and imagination. She describes her approach as an unconscious unraveling of personal and collective experiences, where each stroke of the brush or line on the page becomes a vessel for the unspoken narratives of the past.

El-Husseini’s work delves deep into themes of identity, resilience, and the human experience, serving as powerful reflections of her heritage and the socio-political landscape of Palestine. Born and raised in Jerusalem, El-Husseini's connection to her homeland is palpable in every stroke of her brush and every detail of her artwork. As a child, Jumana was a student at the Ramallah Friends Girls School near Jerusalem. Her grandfather, Hajj Amin El-Husseini, served as Grand Mufti of Jerusalem during the British Mandate. Following the Nakba, the family settled in Lebanon. After her marriage to Orfan Bayazid in 1950, she majored between 1953 and 1956 in political science at the Beirut College for Women, and then at the American University of Beirut. During that period, she was encouraged by one of her teachers to work on art. It was through her creativity that she began to explore and make sense of the multifaceted layers of her identity.

As the late artist and art critic Kamal Boullata has noted, Beirut’s Palestinian artists generally operated either in the orbit of the PLO in the refugee camps or the more cosmopolitan world of Beirut’s art galleries. El-Husseini was a notable exception, bridging the scenes with art that was both politically committed and aesthetically experimental. From the very beginning, Palestine was her primary source of artistic inspiration, and the city of Jerusalem became a recurring theme in her work. Rather than painting the city “realistically,” however, El-Husseini broke the stone buildings of her youth down to basic, deliberately “naïve” geometric shapes, which she rendered in limited, often cheerful color palettes, occasionally accented with gold. Notably, her depictions of Jerusalem are almost always devoid of people, and their emptiness adds to the dreamlike quality endowed by her strategic use of color and negative space. With celestial and oneiric effects, the artist allows the viewer to gaze at Jerusalem as if looking through her dreams.

Her work often incorporates symbolism and imagery drawn from Palestinian folklore, literature, and daily life, offering viewers a window into the rich tapestry of Palestinian heritage. One of the recurring themes in El-Husseini's art is the resilience of the Palestinian people. In addition to her thematic depth, El-Husseini's artistic style is characterized by its emotional resonance. Her ability to evoke empathy, spark dialogue, and challenge perceptions through her art has earned her a dedicated following and solidified her place as one of the most influential voices in contemporary Palestinian art.

Jumana El-Husseini / Untitled, 1973 Dalloul Art Foundation.

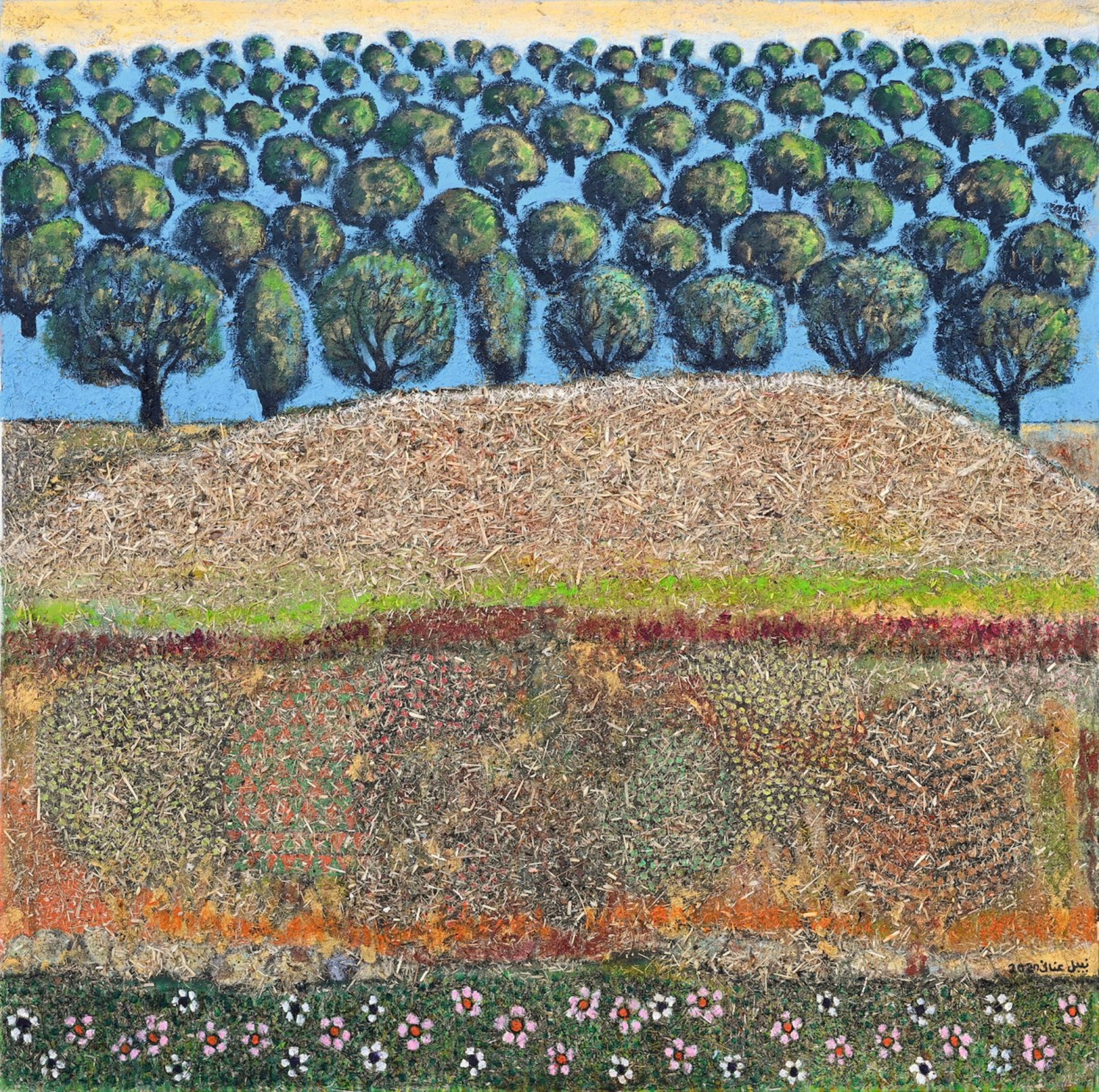

Anani’s artistic practice evolved against the backdrop of profound socio-political upheaval. Yet, amidst the upheaval, he found solace and inspiration in the enduring landscapes of his homeland and its people. Shaped by the serenity of Halhul's hills and the warmth of family gatherings, it provided a sanctuary from the turmoil of occupation. His grandfather, Ali Daoud, a Sufi sheikh, imparted spiritual wisdom and a deep connection to Palestinian heritage. These formative experiences infused Anani's art with a profound sense of nostalgia. He studied Fine Art at Alexandria University, Egypt, in 1969 and upon returning to Palestine, he embarked on a dual career path, serving as both an artist and an art teacher-trainer at the UN college in Ramallah. 1972 marked a significant milestone in the artist’s trajectory as he unveiled his inaugural exhibition in Jerusalem. His work, spanning a diverse range of mediums including painting, ceramics, and sculpture, have captivated audiences with their innovative use of local media such as leather, henna, natural dyes, and wood.

Anani's artistic oeuvre is a profound exploration of Palestinian culture and serves as a testament to resilience with themes ranging from heritage to the landscapes of Palestine. Central to his iconography is the theme of the motherland, symbolized by the figure of the Palestinian woman. As he once remarked, "Most of my artworks included landscape paintings, which helped me to escape the painful reality we live in." As the head of the League of Palestinian Artists and a key figure in the establishment of the first International Academy of Fine Art in Palestine, he has championed the elevation of Palestinian art internationally. Yet, the most profound aspect of Anani's journey lies in the intersection of art and activism. During the First Intifada, Anani emerged as a pioneering force in the New Vision Movement, advocating for artistic innovation and resistance against Israeli occupation. Alongside fellow artists, he boycotted Israeli products and embraced local materials as a means of asserting Palestinian sovereignty over artistic expression. His use of leather, henna, and natural dyes not only honored Palestinian heritage but also served as a powerful act of defiance against the forces of occupation. Along with friend and colleague Suleiman Mansour, Anani was appointed by the Society of Inash Al Usra, an Al Bireh-based civil society organization, to research Palestinian visual heritage in the 1980s. The two visited several villages to study traditional Tatreez, and these traditional patterns and motifs have held particular significance in Anani's work ever since.

Nabil Anani - Excerpts From The Documentary “The Art Residency”

“We have become refugees, without a country, without dignity, without home.”

― Liana Badr, The Eye of the Mirror

Liana Badr (ليانة بدر) stands as a towering figure in the world of Palestinian literature and arts. Her talents encompass poetry, prose, filmmaking, and journalism. Her contributions have not only enriched Palestinian culture but have also resonated globally. Born in Jerusalem to a nationalist family and raised in Jericho, she earned a BA in philosophy and psychology from Beirut Arab University but was unable to complete her MA due to the outbreak of the Lebanese civil war. Badr has been actively involved in various Palestinian women's organizations and worked as an editor for the cultural section of Al Hurriya Review. Following the 1982 Palestinian exodus from Lebanon, she lived in Damascus, Tunis, and Amman before returning to Palestine in 1994.

Badr published her first novel, "A Compass for the Sunflower," in 1979 in Beirut. Since then, she has authored short story collections, novellas, a biography of poet Fadwa Touqan, and five children’s books between 1980 and 1991. Her works explore themes of women, war, and exile. One of her notable works, "The Eye of the Mirror" (1991), is a narrative account of the 1975-76 siege and fall of Tal al-Zaatar in Beirut during the Lebanese civil war. Through her protagonist Aisha, Badr addresses the collective Palestinian trauma and the struggle for liberation from Israeli occupation. Aisha's story reflects the Palestinian desire for freedom and highlights the dual oppression faced by women—by both traditional societal norms and the war itself. Badr's portrayal undermines the masculine discourse that often marginalizes women's war experiences, emphasizing their crucial role in narrating and preserving Palestinian memory. Aisha's body in the narrative symbolizes the collective plight of Palestinian women, victims of both societal constraints and the brutalities of war.

As a poet, she captures the struggles and dreams of her people. Her words are infused with lyrical beauty and emotional depth. In her novels, she portrays the human experience against the backdrop of conflict and displacement. Through richly drawn characters and vivid narratives, she offers profound insights into the spirit of her homeland and challenges stereotypes. As a filmmaker, Badr brings her stories to life and sheds light on the Palestinian experience.

Samira Badran’s artworks focus on her perceptions of the Palestinian reality under occupation. The artist draws inspiration from her father Jamal’s influential role in her artistic development. Her artistic journey began at an early age, as she found solace and expression through creative endeavors. Her upbringing in Palestine, marked by the realities of conflict and displacement, instilled a deep sense of empathy and a desire to give voice to those whose stories often go unheard. Graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts in Cairo in 1976, she further honed her skills in etching and painting at the Accademia Delle Belle Arti in Florence from 1978 to 1982.

Badran's works offer poignant reflections on the Palestinian reality under occupation, exploring themes of collective memory, confinement, and immobility. She is known for her experimentation with diverse techniques and mediums, including ink drawings, watercolor, acrylic painting, collage, photography, and animation. Using this broad range of media and often appropriated or found images, Badran disassembles and then reconfigures the details in her enigmatic, multi-layered works. Inspired by apocalyptic visions, her paintings depict whirling flames and odd machinery pieces amidst fragmented debris and dismembered human limbs, evoking a sense of chaos and confinement. Her powerful work sheds light on the enduring struggles and resilience of the Palestinian people. At the heart of Badran's work lies a commitment to challenging stereotypes and reclaiming narratives often overshadowed by geopolitical discourse. Her art serves as a platform for dialogue encouraging viewers to confront uncomfortable truths.

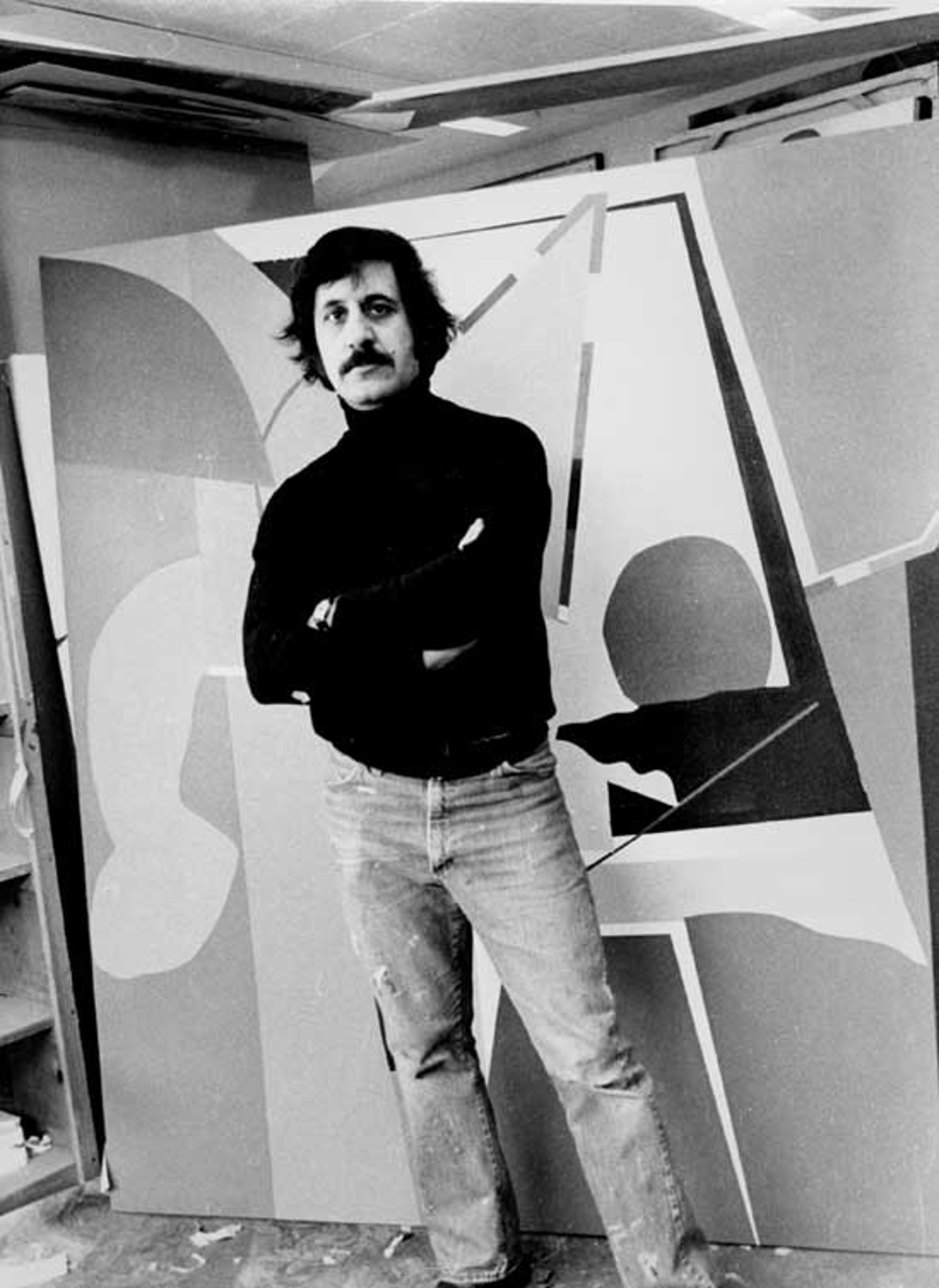

A pioneering Palestinian artist and writer who was born in Jerusalem and grew up amidst the turmoil of occupation and displacement, Boullata's early experiences deeply influenced his artistic journey and commitment to preserving Palestinian cultural heritage. Boullata grew up in the Christian Quarter of the Old City, which fell under Jordanian rule after the Israeli occupation of West Jerusalem in 1948.

In the absence of an art school in Jerusalem, Boullata developed his artistic talent by himself. During the summer holidays, his parents would send him to the workshop of Khalil al-Halabi (1889–1964), well known for his painting of icons. However, his real passion was to draw scenes from life and the street where he lived. Art collectors in the Jordanian diplomatic corps sought to acquire his watercolors, which he painted in their presence. The money he made selling his paintings enabled him to travel to Italy where he spent four years (1961–65) studying art, graduating from Rome's Accademia di Belle Arti, followed by three years (1968–71) at the Corcoran Art Museum School in Washington, DC. Influenced by modernist and abstract art movements, Boullata developed a distinctive style characterized by geometric forms, vibrant colors, and intricate patterns.

Boullata's artwork served as a powerful vehicle for exploring themes of exile, memory, and resistance. Through his paintings and mixed-media works, he sought to challenge stereotypes and misconceptions about Palestinian culture, offering multi-layered perspectives on the Palestinian experience. In addition Boullata was also a prolific writer, publishing books on Palestinian art. His analyses and critical perspectives helped to elevate the discourse surrounding Palestinian art and foster greater understanding of its cultural heritage. Some critics have cited his work as part of the Huruffiya movement, a loose and pan-Arabic consortium of artists who created abstractions out of Arabic text.

In his later life Kamal was awarded Fulbright Senior Scholarships to conduct research on Islamic art in Morocco. Kamal, whose work has been exhibited all over the world, lived in Menton in Southern France, and lived his last years in Berlin until passing in 2019, ( he was buried in his homeland at the Cemetery of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem at Mount Zion next to his family and ancestors).

“Palestine informed his practice, his spirit, and his self, and it was through it that he observed and understood things. The truth is, Palestine was much more than the country of his birth and where he spent 18 years of his life; it was what inspired him to imagine. Though he was forced to live in exile, Palestine never left him, and because it was always present in his mind, in his own way, Kamal felt liberated. Art for us was always about liberation, and he was the most liberated person I know. As always, I look forward, my friend”. - Steve Sabella

Mahmoud Darwish, a towering figure in modern Arabic literature, made a profound impact during the 1970s and 1980s, both as a poet and as a voice for Palestinian identity. Born in the village of al-Birwa, Darwish's early experiences of displacement and loss deeply influenced his writing. Darwish’s early education took place in the context of this displacement. He excelled in school, showing a talent for poetry at a young age. His first collection of poems, Asafir bila ajniha (Wingless Birds), was published when he was just 19 years old. The themes of exile and yearning for a lost homeland were already evident in his early works. By the 70s, he had become a prominent figure in the resistance movement, using his poetry to articulate the pain of exile and the longing for homeland. His works from this period, such as "Unfortunately, It Was Paradise" and "The Hoopoe," are celebrated for their powerful imagery and emotional depth, capturing the collective grief of the Palestinian people.

In 1970 Darwish studied at the University of Moscow. This was the beginning of a long period of exile that saw him living in various countries, including Egypt, Lebanon, France, and Tunisia. Each place added new dimensions to his poetry, enriching it with diverse cultural and intellectual influences. While in Beirut, Darwish joined the PLO and worked as an editor for its research center. This period was particularly productive, resulting in some of his most celebrated works, such as Mahmoud Darwish: Selected Poems (1973). His writings from this era reflect a deep engagement with themes of identity, resistance, and the struggle for justice. Darwish's poetry was not only a form of artistic expression but also a means of political activism, resonating with Palestinians and supporters of their cause worldwide.

During the 1980s, Darwish continued to gain international acclaim, cementing his status as a leading poet of the Arab world. His poetry readings attracted large audiences, and his works were translated into numerous languages, bringing the Palestinian narrative to a global audience. Darwish's work from this period, including the renowned collection "Memory for Forgetfulness," reflects a mature, contemplative voice grappling with the complexities of identity and belonging. His impact during the 1970s and 1980s remains significant, as he not only enriched Arabic literature but amplified the Palestinian struggle on the world stage. Unlike many political artists at the time, he consistently recognized the humanity in both himself and his oppressors. The humanism that permeates his work stands as a testament to his greatness.

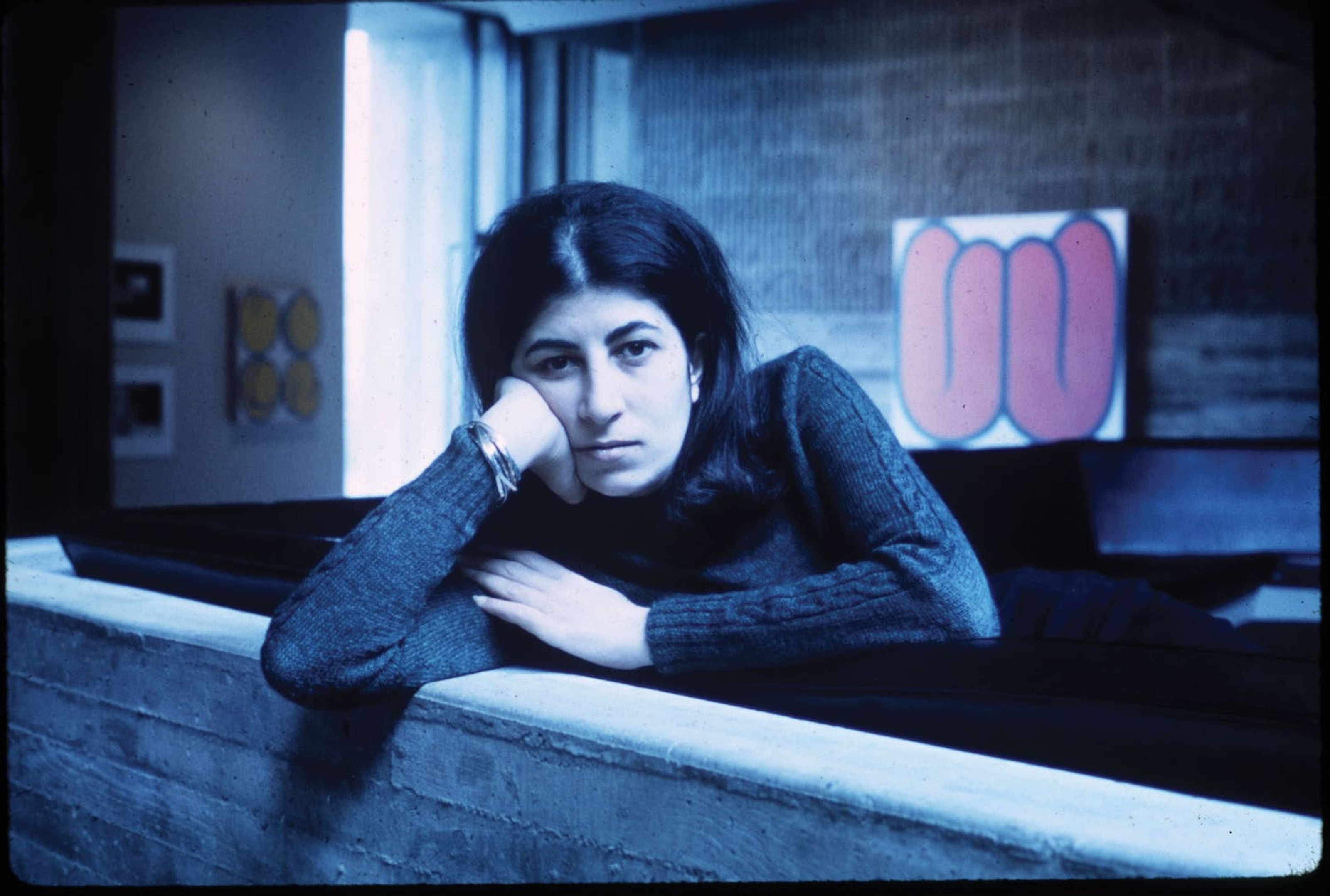

Samia Halaby was displaced along with her family during the Nakba, and this experience of displacement and the subsequent life in exile have significantly influenced her artistic vision and thematic explorations. Her work reflects a deep connection to her homeland while also engaging with broader themes of identity, and resistance. Between the ages of 11 and 14, Halaby lived in Beirut with the hopes of returning home one day. However, the entire family moved to the U.S., where adapting was challenging, and where Halaby faced profiling. Reflecting on her experience, she observes, “At present, we are blamed for our own victimization. I am accused of being antisemitic, of being guilty of my oppressors' crimes, the oppressor who stole and still lives in my house in Yafa.” It was these experiences that fueled her political activism and deeply informed her art.

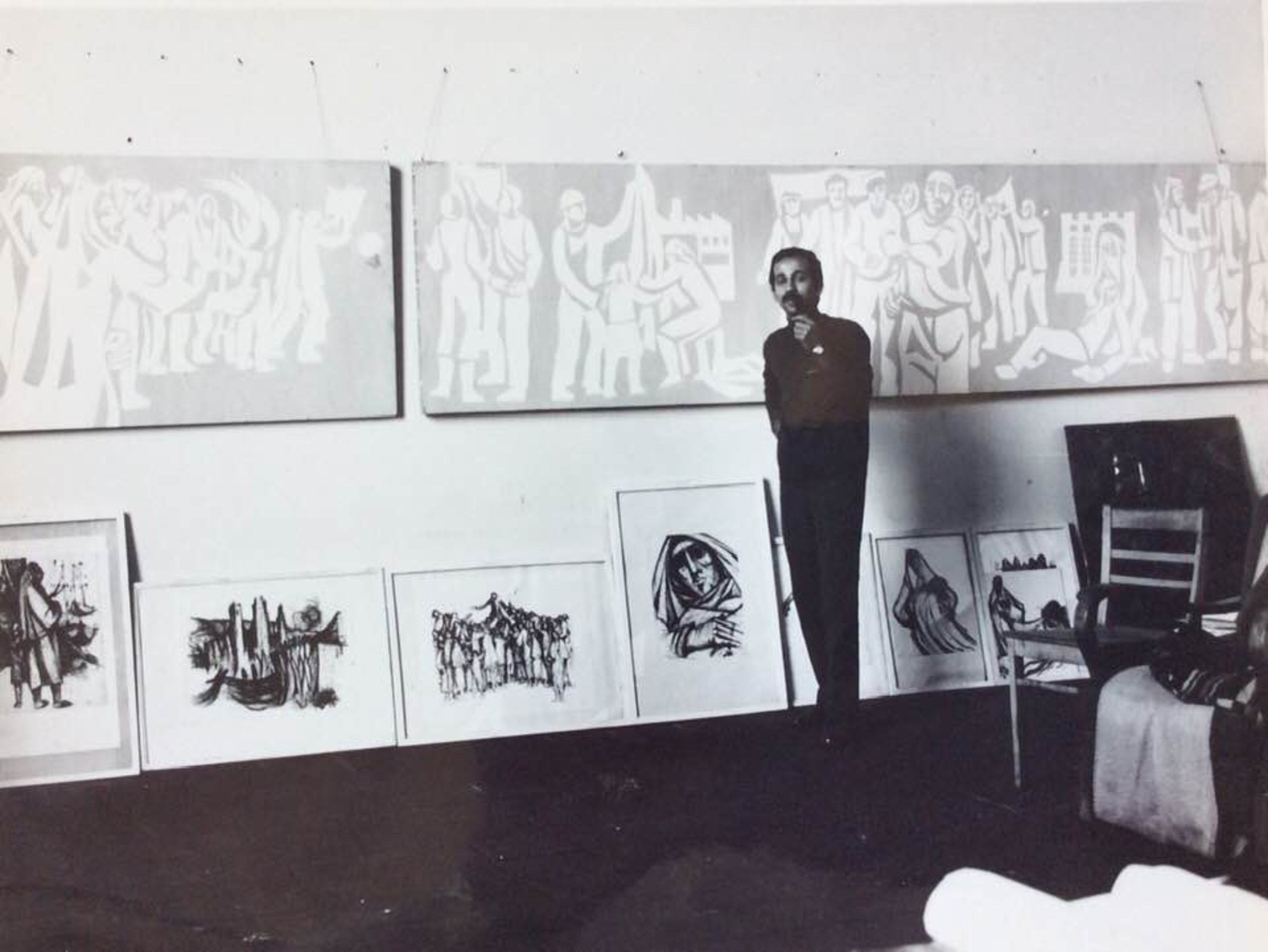

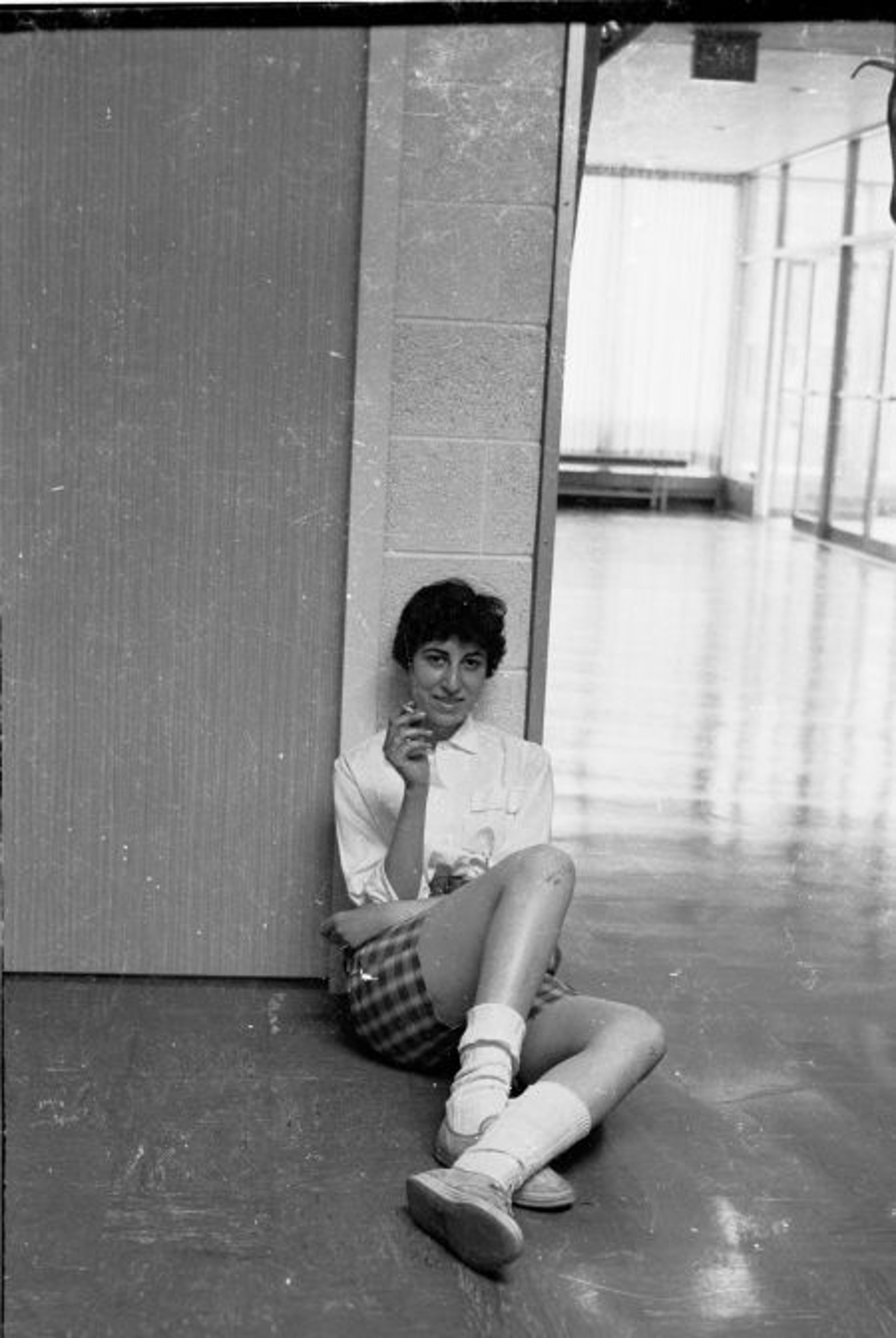

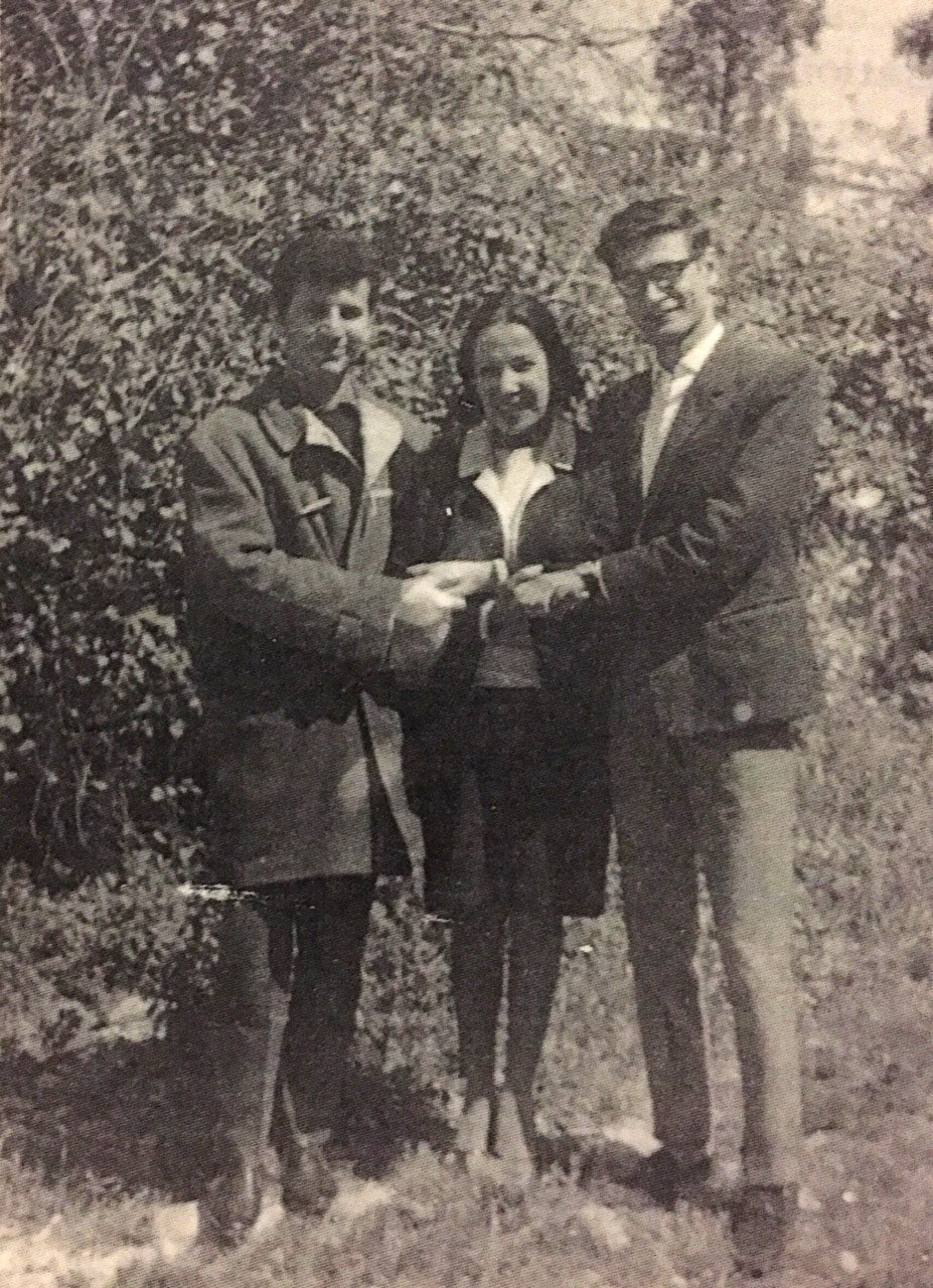

Samia Halaby at Judith Nelson show at New England College, 1974 © Don King.

In the mid 70’s, Samia’s career blossomed as she established herself as a significant figure in the art world, particularly within the abstract art movement. This period marked a pivotal phase in her artistic development and activism, characterized by her innovative explorations in abstract painting and her deepening commitment to political causes. She drew inspiration from a variety of sources, including Islamic art, modernist traditions, and her own experiences. Her work sought to challenge and expand the boundaries of Western abstract art by incorporating elements of her cultural heritage, thus introducing a unique non-Western perspective to the modern art scene. Also in the 1970s, she introduced a groundbreaking undergraduate studio art program at various art departments throughout the Midwest, aiming to provide a comprehensive and innovative art education. Her approach emphasized the importance of abstract art and sought to integrate diverse artistic traditions into the curriculum.

In 1972 Halaby became the first full-time female associate professor at the Yale School of Art, a position she held for nearly a decade. During her tenure at Yale, she influenced a generation of young artists, encouraging them to explore new dimensions in abstract art and to consider the socio-political contexts of their work. Her innovative teaching methods and dedication to her students left a lasting impact on the academic community. Her writings on art history, pedagogy, and aesthetics have appeared in numerous publications over the last three decades.

Samia Halaby / Jerusalem, My Home, 2014. Acrylic on canvas.

Democracy Now! “Palestinian Artist Samia Halaby Slams Indiana U. for Canceling Exhibit over Her Support for Gaza”

Cover of Shuʾun Filastiniyya 1980, issue 105, designed by Laila Shawa.

Cover of Shuʾun Filastiniyya 1980, issue 107, designed by Jumana al-Husseini.

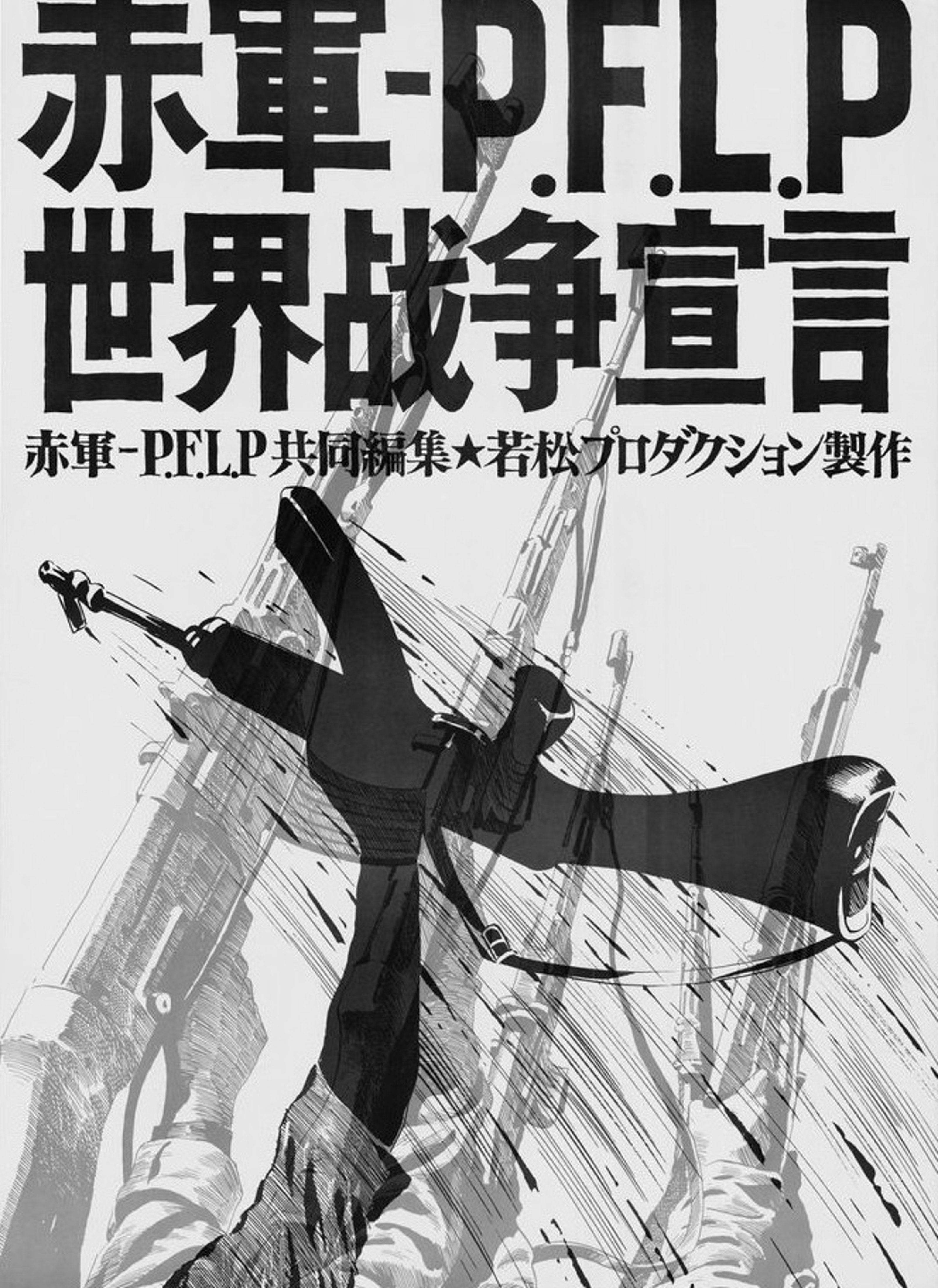

Ghassan Kanafani, often referred to as "the commander who never fired a gun," was a legendary figure in the Palestinian liberation movement. In exile Kanafani worked at a printing press, distributed newspapers, and took up a job in a restaurant. Despite these demanding jobs, he pursued his studies day and night, earning an intermediate school certificate in 1953. He subsequently became an art teacher in UNRWA schools in Damascus. His contact with Arab political activists began in 1953 when he met George Habash and started writing for the weekly magazine al-Ra'i. Kanafani's engagement with political movements deepened as he connected with the Arab Nationalist Movement.

After obtaining his secondary school certificate, Kanafani joined his sister in Kuwait in 1956, where he worked as an art and athletics teacher. Concurrently, he enrolled in the Arabic Department of Damascus University while remaining active in the Arab Nationalist Movement and at the Arab Cultural Club. Kanafani contributed to the weekly magazine al-Fajr, published by the movement, and in 1957, he published his first story, “A New Sun.” In 1960, Kanafani moved to Beirut where he joined the editorial board of al-Hurriyya magazine and later became the editor of al-Muharrir and its supplement Filastin. His editorial journey continued with al-Anwar's weekly supplement until 1969.

The Palestinian cause is not a cause for Palestinians only, but a cause for every revolutionary, wherever he is, as a cause of the exploited and oppressed masses in our era. - Kanafani

Kanafani played a crucial role in founding the PFLP in 1967, where he was elected to its political bureau and became its official spokesman and media head. He edited al-Hadaf, the movement's magazine. With his unfaltering belief in the cause, Kanafani captured the attention of the West through iconic interviews. His commitment to resistance made him a symbol of the Palestinian struggle worldwide and helped redefine the Palestinian struggle from a nationalistic form of Pan-Arabism to a more Marxist-Leninist revolutionary movement. Though Kanafani supported armed resistance, he used his pen and prose as his weapon of choice. This approach proved to be highly effective and influential, so much so that Israel viewed him as a significant threat. He was assassinated by Mossad in Beirut on July 8, 1972, in a car bombing that also claimed the life of his niece, Lamis.

Kanafani’s short stories became the basis of later films such as Return to Haifa (1982) which recounts the story of a Palestinian family returning to their home now occupied by an Israeli couple who adopted the baby son they left behind.

Born in Jerusalem, he immigrated to the U.S with a fine arts scholarship to Ohio Wesleyan University, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts in 1963. In 1965, he then earned a Master of Fine Arts at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Detroit. In a personal statement from 1996, he described the impact the loss of Palestine had on him:

My family lived in the new sector of Jerusalem, Palestine until 1948 when we were all forced to leave our homes under a hail of bullets and explosions during the war. We left everything behind including all our family albums. I was seven years at the time, and the ensuing years were extremely difficult for a family that had been accustomed to a comfortable cultured way of life. The dispossession of a homeland took its toll on our entire family. As an impressionable child I witnessed all kinds of upheavals and painful situations and learned to internalize the agony of our impoverished status. My therapy from all this was in drawing. I drew figures, and tormented faces, old wrinkled people. From an early age, I rejected bourgeois values, pretty objects of art, and political deception. Even then, I knew that to pursue art would be a lonely voyage.

His artistic evolution was a reflection of his personal growth and exploration, with elements of the human figure persisting as symbolic motifs throughout his work. In his own words, Khoury described his artistic philosophy as rooted in a synthesis of modern traditions, drawing inspiration from luminaries such as Klee, Gorky, Kandinsky, and Matisse. His oeuvre, characterized by a dynamic interplay of shape, line, texture, and color, embodied a harmonious fusion of diverse influences, ranging from Cubism to Abstract Expressionism. Central to Khoury was his connection to his heritage, which found expression in the incorporation of Arabic writing, Islamic design, and Byzantine imagery into his work. This rich tapestry of cultural influences imbued his art with a sense of depth and complexity, inviting viewers to explore the intersection of tradition and innovation.

Khoury was also a devoted educator, shaping the minds of aspiring artists at Central Michigan University for three decades. His commitment to nurturing talent and fostering creative growth left an indelible imprint on generations of students, instilling in them a passion for artistic exploration. His dedication to promoting peace through art was exemplified by his participation in the "It is Possible" exhibit in 1988, where his abstract compositions served as a powerful testament to the human spirit's capacity for resilience and hope. His mural depicting immigrant life in Dearborn, Michigan, stands as a poignant reminder of his commitment to capturing the essence of the human experience through art.

Born in Gaza, Kamal Nasser was a poet and activist who fearlessly voiced his convictions in the pursuit of Arab unity and against the oppressive Israeli occupation of Palestine which made him a prime target for Israeli authorities. In 1967, Kamal was forcibly deported from Palestine, and rather than succumb to exile, he found renewed purpose in his struggle. Joining the PLO in 1968, Kamal swiftly rose to prominence, earning a place on its Executive Committee in 1969. For four years he directed the PLO’s media tirelessly working to raise awareness of the Palestinian cause. His words resonated deeply with those who shared his vision of liberation and justice. Filastin al-Thawra featured a diverse range of literary and cultural content. This included serialized memoirs and diary-like entries documenting the Palestinian Revolution, prose and poetry, analytical pieces on the role of periodicals and literature in the revolution, prison literature, tributes to literary martyrs of the revolution (especially those assassinated by Israeli forces), and reviews of revolutionary films produced by the PLO’s Film Unit. In its early issues, the literary section was titled “al-Fann wa al-Thawra” (“The Arts and the Revolution”), which later evolved into titles such as “Adab wa Fann” (“Literature and Art”), “Adab” (“Literature”), and “Adab wa Thaqafa” (“Literature and Culture”). A review of the tables of contents reveals that it was common for literary figures to contribute both literary content and political analysis pieces.

He was assassinated by Israeli forces in 1973 during a raid on his home in Beirut.

Born in Ain Karem, a village just south of Jerusalem, Nawash's journey as an artist was intricately woven with the threads of trauma, and displacement. When he was just ten years old, he crafted his inaugural artwork portraying Salah al-Din, the iconic medieval sultan who reclaimed Jerusalem for Muslim sovereignty. At fourteen, Nawash and his family fled their home due to Zionist occupation. The haunting echoes of the Deir Yassin massacre reverberated in their exodus, propelling them on a traumatizing first by foot and later aboard a truck journey, until they found sanctuary across the river in Jordan.

After finding stability in Amman, at seventeen, he set for Italy, leaving behind his family in a difficult farewell. The image of his father's tearful blessing, accompanied by the timeless advice to "Rely on God," remained vivid in Nawash's mind even in his later years. Arriving in Rome without prior admission to any school, Nawash undertook the entry exam for the Accademia di Belle Arti di Roma and triumphed. Amidst the backdrop of a burgeoning liberation movement, his passion for his homeland intensified, finding poignant expression in his paintings. His canvases became a testament to the plight of his people, and became a sanctuary where he wrestled with personal traumas. Nawash often painted mysterious figures created with surrealistic detail, floating in cloudy, muted backgrounds. Their aimless movement conveys a sense of being lost and radiates raw energy, capturing the silent suffering of people trapped in collective trauma.

Nawash embarked on a quest for artistic mastery that spanned two decades, earning three additional diplomas in etching, lithography, ceramics, and restoration from prestigious institutions across Europe. Palestine, an indelible imprint on his soul, emerged as the central motif in his oeuvre, reflecting the agony of a people besieged by existential unrest. For him, the canvas was a mirror reflecting the collective consciousness of Palestine and the broader Arab World.

Born in Safad, Salameh's journey is a tapestry woven with threads of exile, activism, and artistic exploration. His journey commenced with the Nakba, which forced him and his family to seek refuge in Syria. It was here that the seeds of his artistic passion were sown. He pursued painting at the University of Damascus, graduating in 1972. These formative years infused his art with a profound understanding of human struggle and resilience. He worked for the PLO, crafting posters and prints that echoed the fervor of resistance against occupation. His art became a conduit for the Palestinian narrative, a visual testament to the plight of a people yearning for freedom. In 1975, Salameh's quest for artistic enrichment led him to the Ecole Superieure Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Graduating in 1981, he made France his home, immersing himself in its cultural milieu while retaining a steadfast connection to his Palestinian roots.

His tenure at UNESCO Headquarters, where he worked in the Department of Arabic Literature, provided a platform to intertwine his artistic endeavors with a commitment to cultural preservation. His tireless advocacy for Palestinian culture earned him recognition, including the prestigious Order of Culture, Arts, and Sciences bestowed by the Palestinian president in Ramallah in 2005. Throughout his career, Salameh's art served as a prism through which the complexities of occupation, displacement, and longing were refracted. His abstract expressionist paintings, adorned with bright, luminous colors, evoked landscapes both real and imagined. His use of glowing colors symbolizes not only a defiance against the shadows of oppression but also a beacon of hope for the Palestinian cause. In 1996, Salameh returned to his birthplace in Safad, a poignant homecoming marked by the painful realization that his childhood home no longer existed.

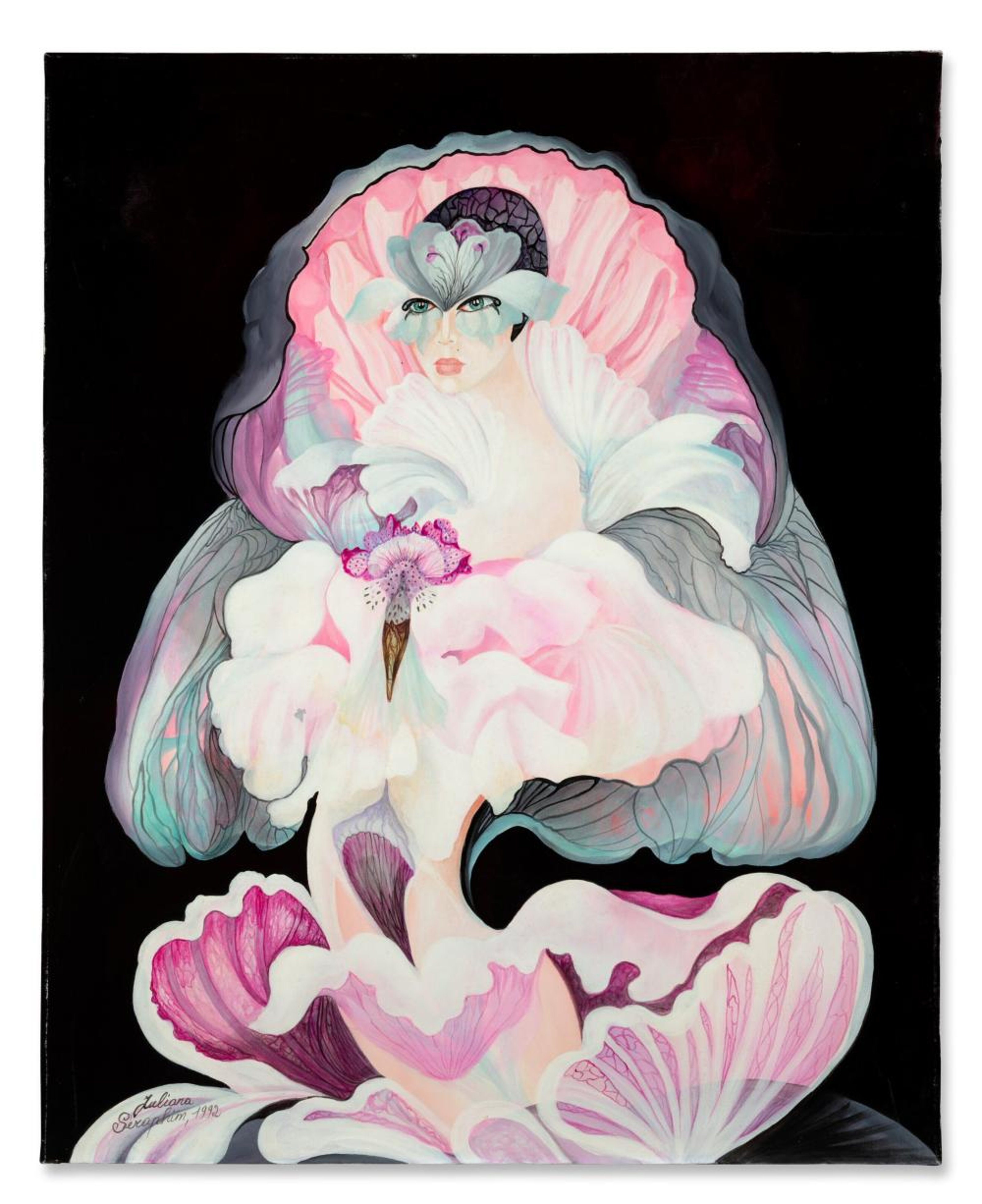

Seraphim emerged as a leading voice among women artists in the Arab world. Born in Jaffa, her artistic journey was shaped by the displacement of her family following an attack on their native city. At fourteen, she found herself part of the inaugural wave of Palestinian artists whose creative journey unfolded in exile. Forced to flee to Sidon by fishing boat, they awaited the opportunity to return home, only to realize a few years later that such a return would be prohibited.

Relocating to Beirut during its “ Golden Age,”1 the Seraphim family embarked on a new chapter in their lives. While her artistic roots were deeply intertwined with her homeland, particularly influenced by her grandfather's home in Jerusalem and the coastal views of Jaffa, she chose not to engage directly with the political discourse of Palestinian liberation in her art. This decision set her apart from what Kamal Boullata, the late Palestinian artist and art historian, termed the “camp artists” – predominantly male, often self-taught individuals who coalesced within refugee camps under the auspices of the nascent PLO. In the vibrancy of Beirut, where music, theater, and art thrived, Juliana found her passion for creativity ignited. Despite not attending university, she dove into the art world, squeezing in lessons with painter Jean Khalife after her work days as a secretary at the UNRWA headquarters.

Juliana Seraphim / Untitled, 1980. Oil on canvas.

Later, Juliana studied in Florence and Paris for her art education, but it was her time in Madrid that truly shaped her artistic vision. There, she met the art critic Carlos Ariane, who pointed her toward India ink as the perfect medium to bring her surreal imagination to life. Her preference for exploring surreal art over political themes in the early 80’s led to her being perceived as divergent from the prevailing narrative surrounding the Palestinian national cause. Immersed in a cultural milieu where discussions on feminism permeated both in Lebanon and Europe where she studied, her expression was influenced by an era characterized by spiritual exploration and advocacy for women's rights.

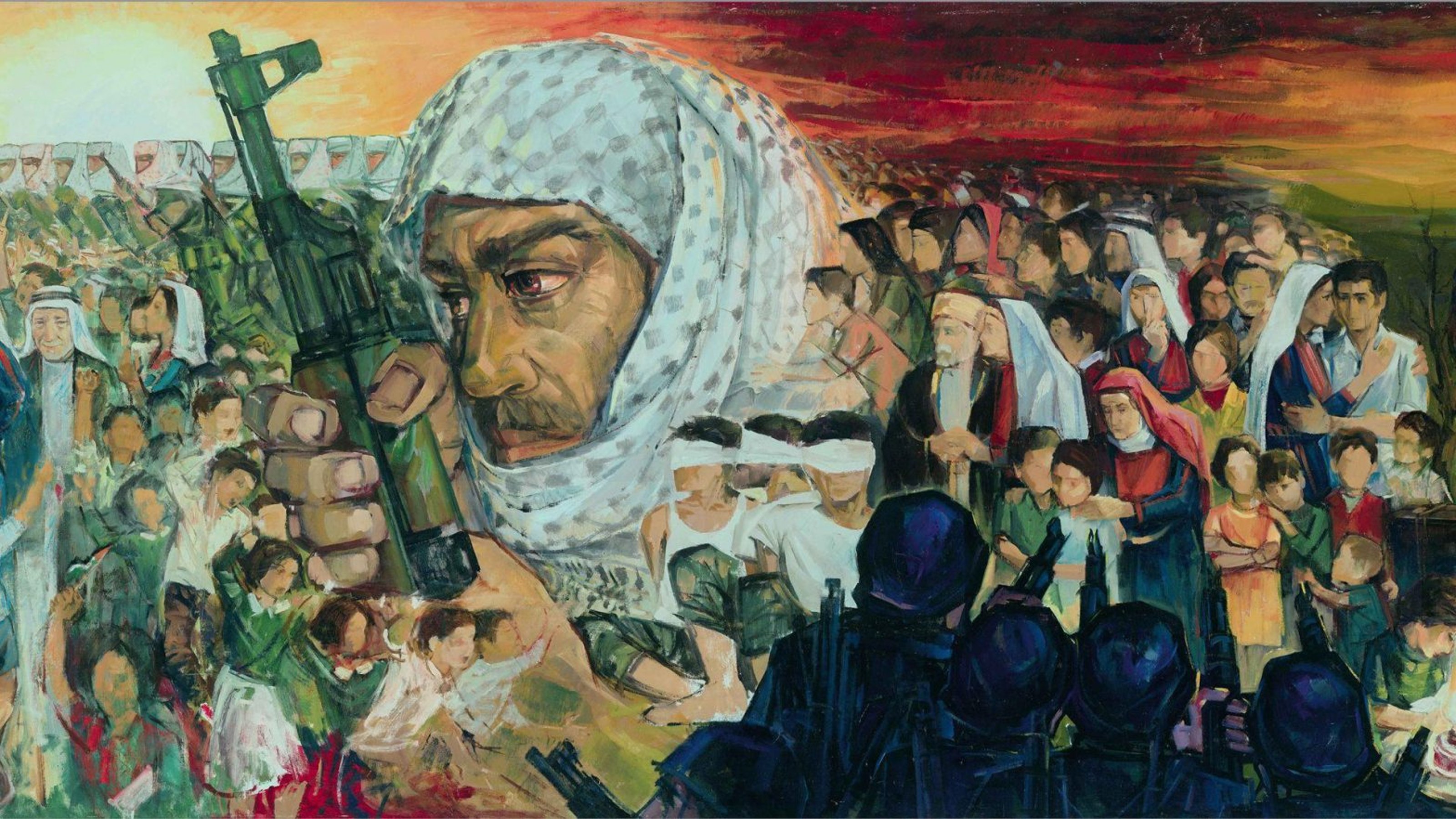

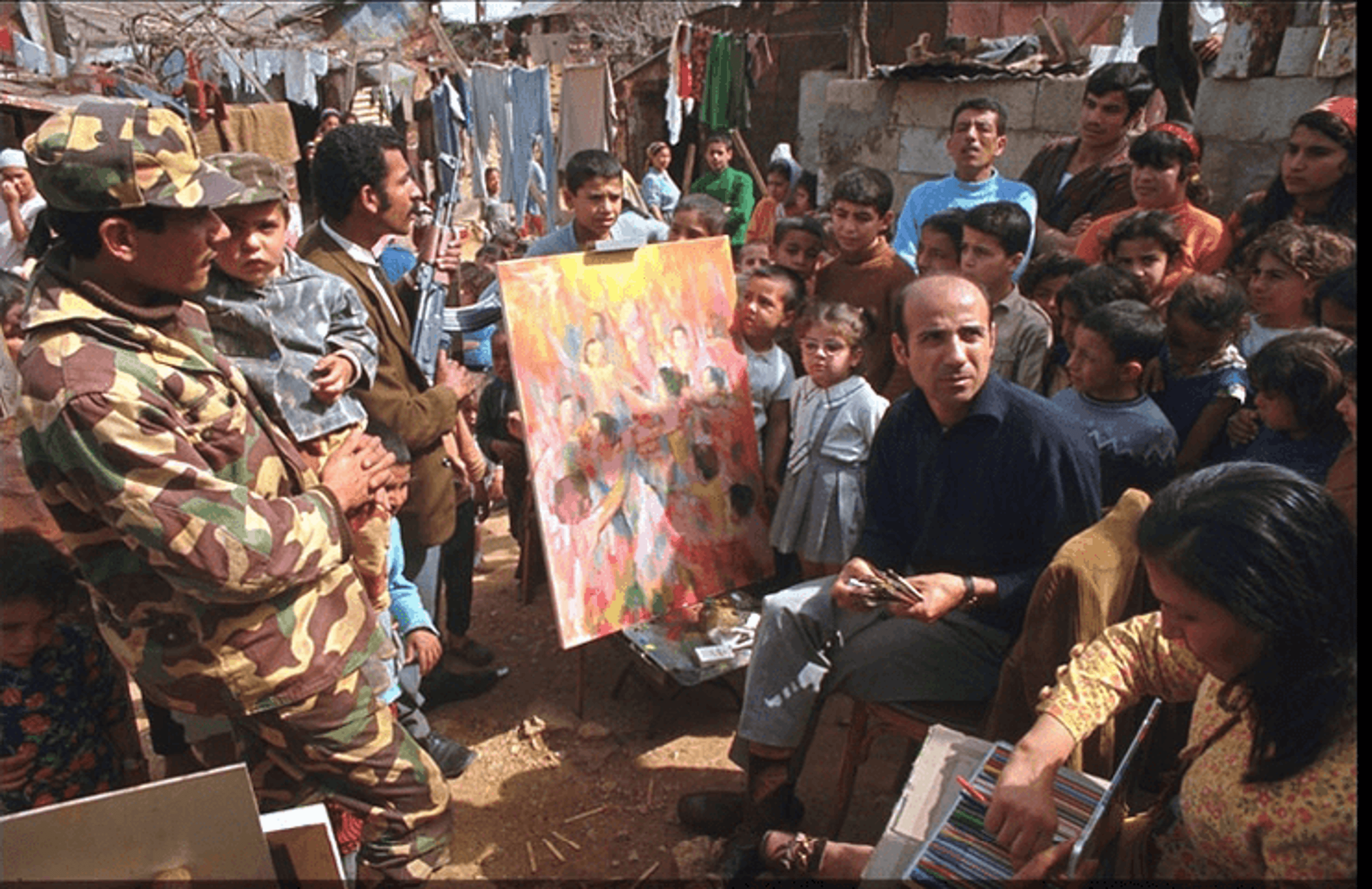

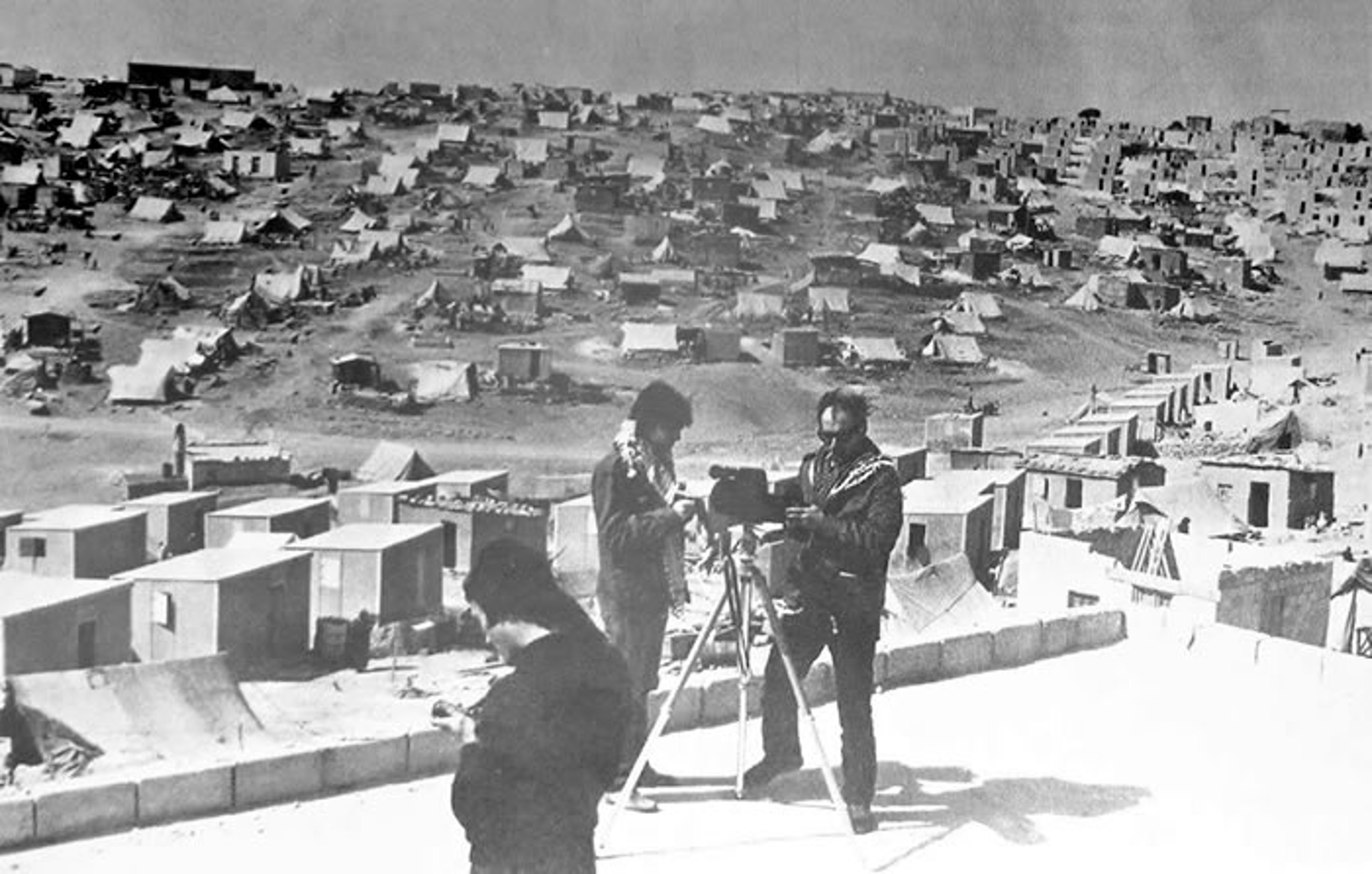

Ismail Shammout is considered one of the most influential Palestinian artists of the 20th century. His work is characterized by its powerful depiction of Palestinian identity and the struggle for justice. The artist was born in Lydda and in 1948 Ismail and his family were among the 25,000 residents who fled their homes and were relocated to the Gaza refugee camp of Khan Younis. Lydda became the site of one of the Nakba’s deadliest massacres of Palestinian civilians and Shammout became one of the hundreds coerced into walking what is now known as the Lydda Death March. Shammout later moved to neighboring Egypt and then Rome to study art at the Art Academy of Rome.

Early on, Shammout developed an expressive figurative style through which he transformed his painful experiences into nationalistic iconography. He began painting roughly autobiographical scenes and later in his career themes encompassing allegorical compositions that stirred pro-Palestinian sentiment. In 1954, Shammout held his first acclaimed exhibition in Cairo, alongside his colleague Tamam El Akhal, whom he married. In 1958, Shammout moved to Beirut, where he became the Director of the Department of Arts and National Culture of the PLO. He designed the PLO’s first logo and created political posters promoting national resistance. These posters adopted an expressive-symbolic style, aligned with the socialist realist art ethos popularized by the Eastern Bloc's cultural regimes. Art, according to this mindset, should communicate messages easily understood by people from all backgrounds, unifying the support of national liberation.

As the Palestinian national resistance grew in the 1970s, Shammout’s narrative paintings reflected determination and optimism. He transformed his somber color palette into a vibrant one, replacing the grim figure of the refugee with a young, robust fighter. He also portrayed women in traditional Palestinian thobes adorned with Tatreez. Drawing inspiration from poetry, such as Mahmoud Darwish’s poem "Lover from Palestine," Shammout visually represented the allegory of Palestine as a female body. “Odyssey of a People” - This 6-meter-long painting captures the history of Palestine. It took six months of dedicated daily work. Driven by emotion and passion, it stands as the most important work of his career. Directly consigned from the artist’s family, this painting reenters the art world with fresh significance. In 2002, during an Israeli incursion, the painting was hidden by the museum director in a pillowcase and remained hidden until after Shammout’s death in 2006. In 2008, the director’s widow returned the painting to Shammout’s wife.

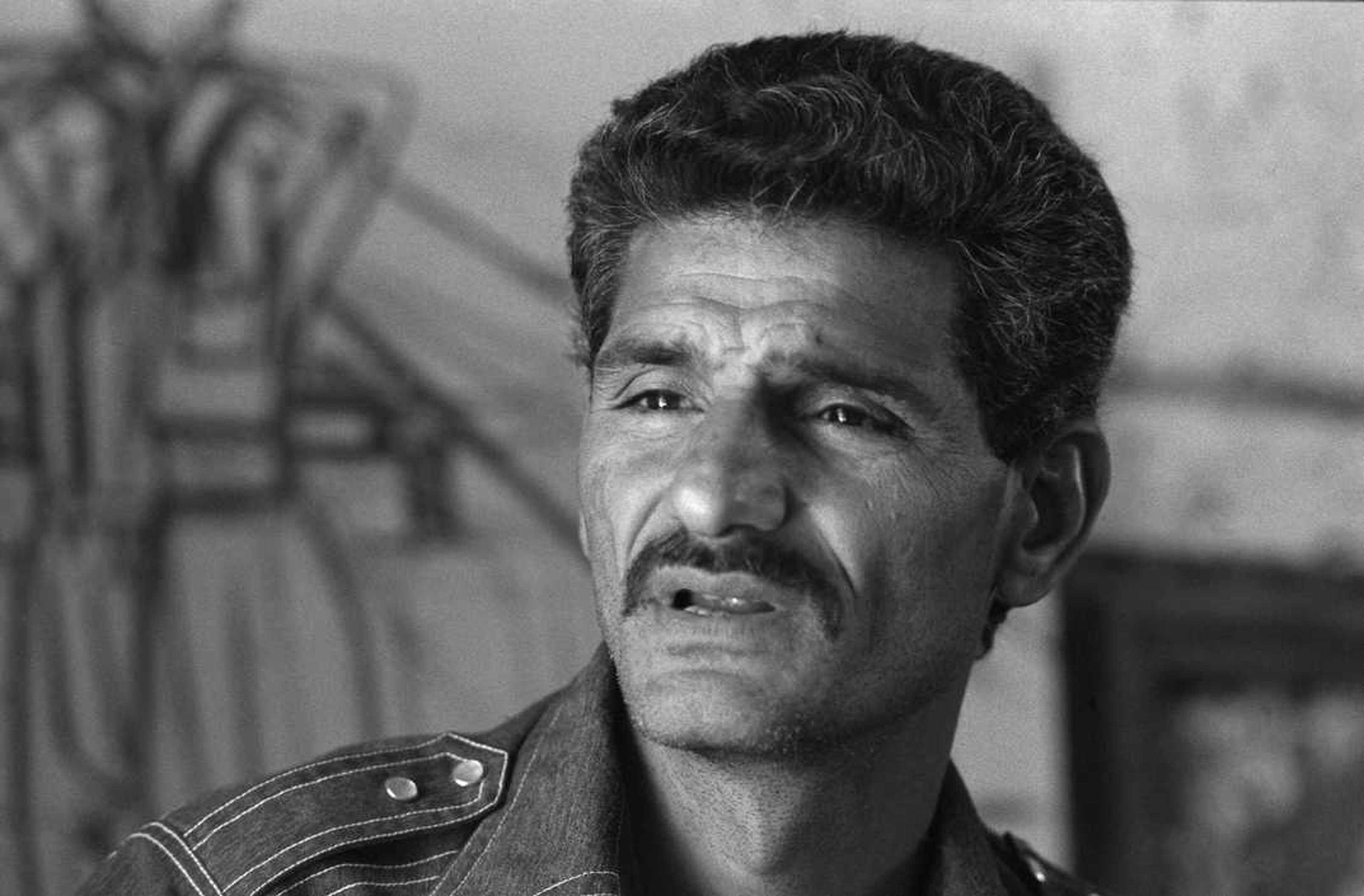

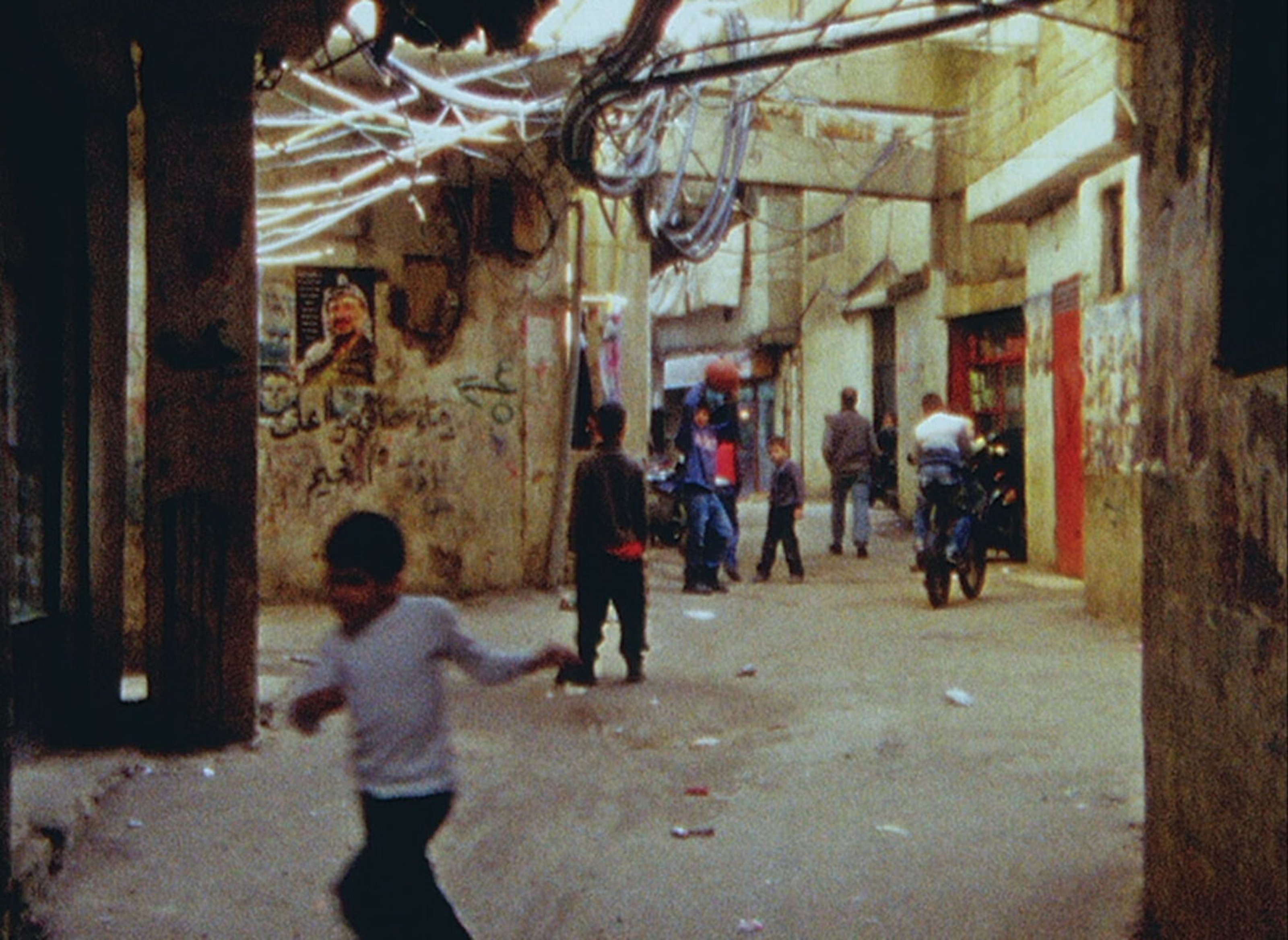

Ismail Shammout working in Tal Al-Zaatar refugee camp, 1973.

The canvas reads from right to left, like the Arabic language, retracing key events in Palestinian history—from the Nakba and subsequent wars of the 60s through the 80s to the establishment of the Palestine Liberation Organization. This historical narrative is juxtaposed with symbols of hope and unity culminating in a dreamlike vision of liberation, peace, and freedom. Shammout intended to map out the odyssey of his people and express his dream of returning home.

Almost every Palestinian, inside or outside of occupied Palestine, inside or outside refugee camps, identified with his paintings. In my childhood, I hardly remember entering a Palestinian house without immediately seeing copies or even originals of his paintings hanging on the walls. Only years later, when I grew up, did I realize what his art meant to his people and the impact it had on them! It was in the early 1950s, at the age of 23, when he created his remarkable, iconic masterpieces Where To? and We Shall Return, in which he tried to express his personal Nakba experie-nce of expulsion and refuge. Here, he simply shared the feelings and experiences of hundreds of thousands of fellow Palestinians who all saw themselves reflected in these works that gained an extremely wide popularity. But in these works, people saw as well the beauty and pride of being “Palestinian” – at a time when darkness was the dominating characteristic that shrouded Palestinian life. - Bashar Shammout (Ismail Shammout's son)

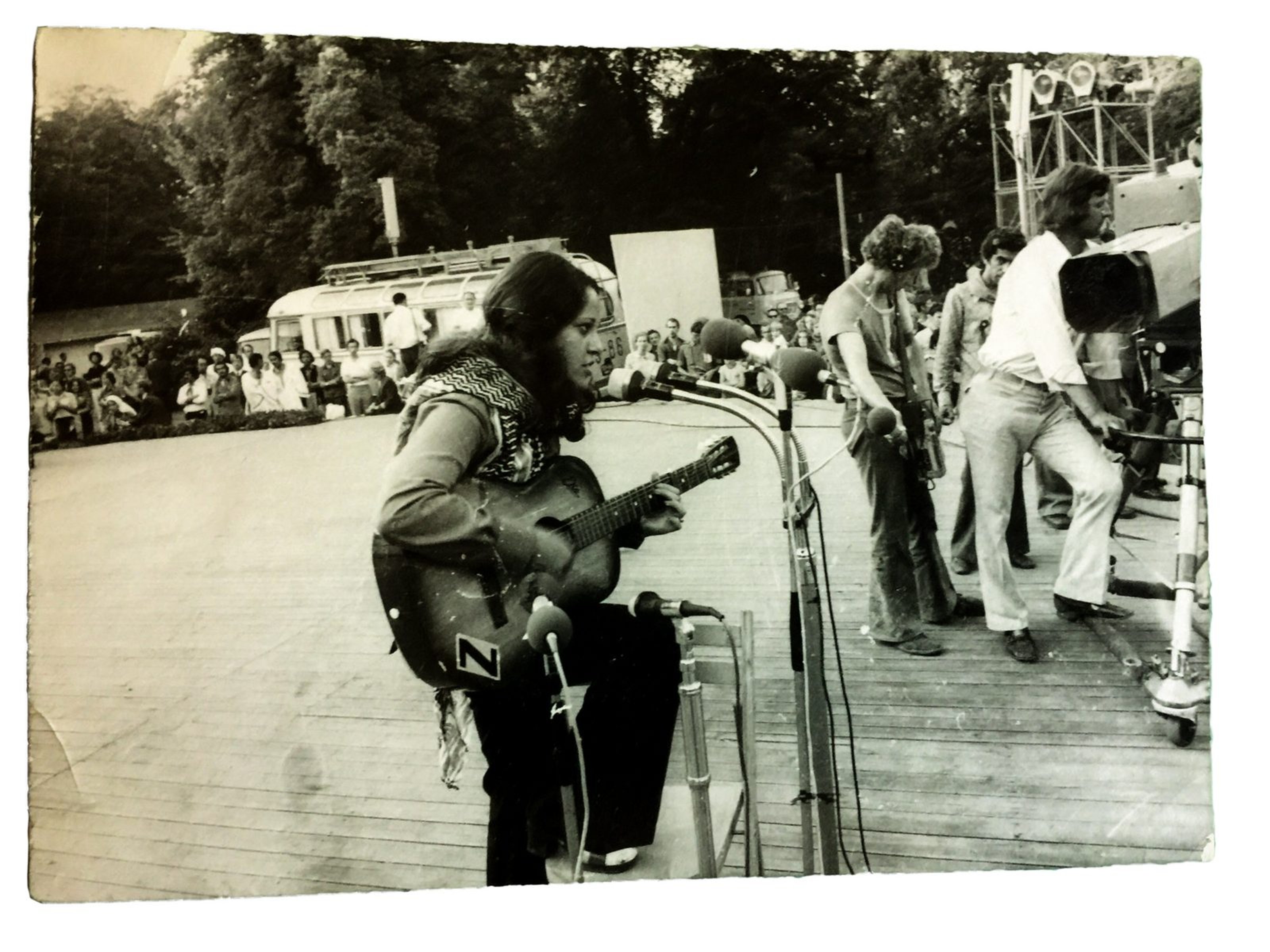

Can’t you hear

the urgent Call of Palestine

tormented, tortured, bruised, and battered

and all her sons and daughters scattered

Can’t you hear

the sweet sad voice of Palestine

She whispers above the roar of the guns

beckoning to all her daughters and sons

Can’t you hear the agony of Palestine

Liberation banner raise it high for Palestine

let us do or die

After putting music together on the guitar, “The Urgent Call” would be Zeinab’s first composition at the age of 16. Her music could be heard at festivals in Lebanon, on Egyptian radio stations and at protests throughout the U.S. in the 70s and 80s.

The four-minute film, shot on 8-millimeter in the mountains of Lebanon in 1972 by Ismail Shammout features then-teenage Egyptian-born Palestinian singer Zeinab Shaath. Thin-browed and effortlessly captivating, Shaath strums her guitar with a keffiyeh around her neck, perched on a rock and dappled in sunlight filtered through surrounding olive trees. Shaath’s imploring voice cuts through the Mediterranean air: “Can’t you hear the urgent call of Palestine? Palestine — tormented, tortured, bruised and battered, and all her sons and daughters scattered.”

A remarkable example of Palestinian protest music in exile, “The Urgent Call of Palestine” was the title track of an EP of four songs produced by the PLO in the early 1970s. Each song is composed by Shaath and entirely in English. Now, more than 50 years after Shaath’s urgent voice first appealed to the world — and decades after the master of the accompanying music video was stolen, left to collect dust in an Israeli military archive — the EP will be reissued March 26 on Bandcamp through the joint effort of two archival record labels: the U.S.-based Discostan and the Palestinian-led Majazz Project.

Laila Shawa was born in 1940, in Gaza, a descendant of one of the oldest Palestinian landowning families. Sent to boarding school in Cairo at a young age, Laila's passion for art flourished, leading her to the renowned Leonardo da Vinci Art Institute in Rome. She honed her craft while rubbing shoulders with icons like the Rolling Stones and Simone de Beauvoir.

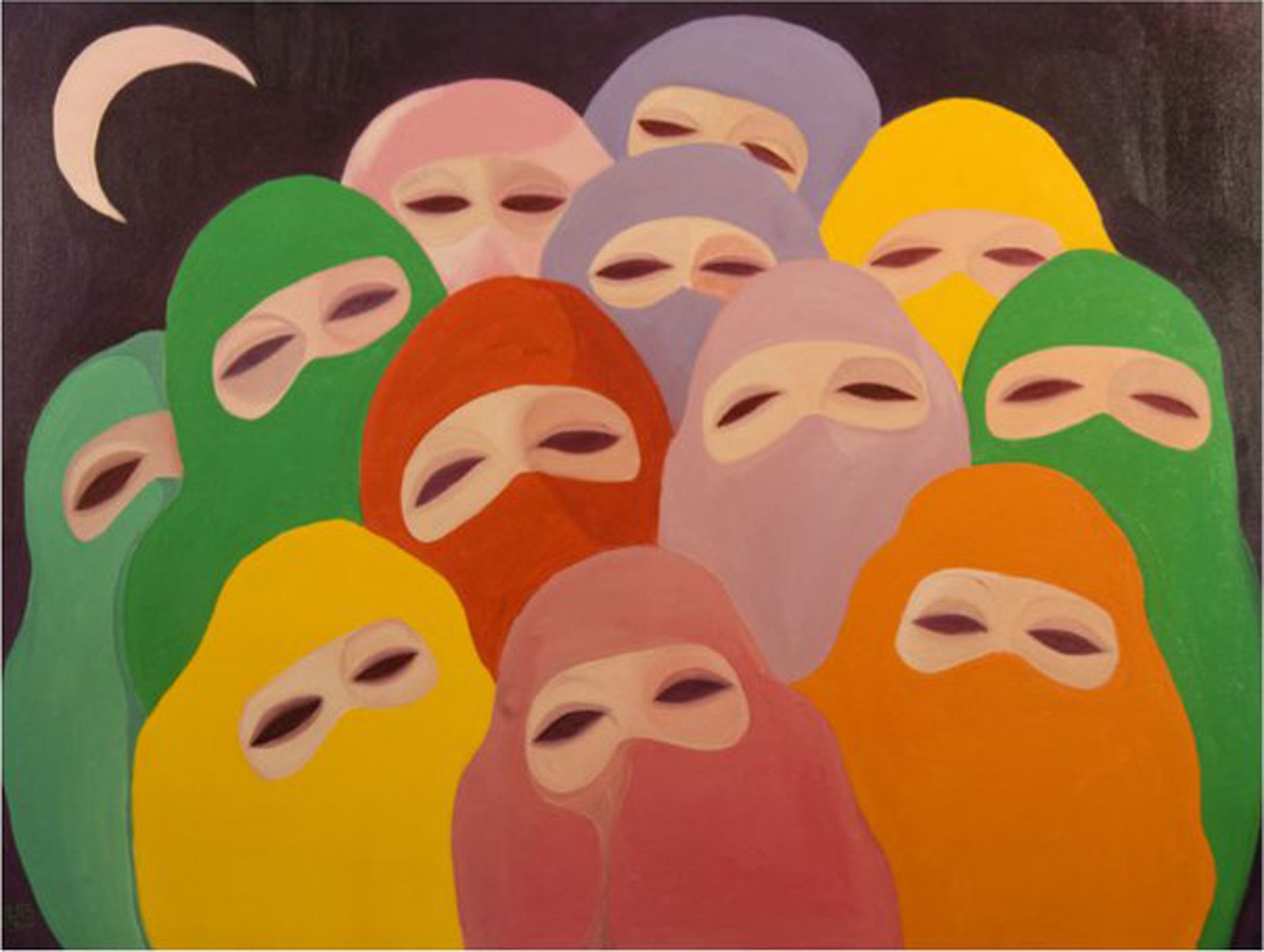

Her artistic odyssey took her to the Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts, where she embraced the expressive ethos of Oskar Kokoschka's alternative art school. Returning to Palestine in 1964, Laila embarked on a mission to empower through art, spearheading arts and crafts education projects in UN-coordinated refugee camps, while also working with the documentary photographer Hrant Nakashian. She co-founded the Rashad Shawa Cultural Centre. Her work is based on a heightened sense of realism, injustice and persecution. The initial impetus for a piece often comes from her photographs, which are later transformed using silk screen printing techniques. Laila's sojourn in Beirut during the late 1960s saw the birth of her iconic "Cities' ' series, vibrant reflections of urban life infused with political undertones. Amidst the upheaval of the Lebanese civil war, she returned to Gaza. Undeterred, Laila's artistic vision transcended borders, as she ventured to London during the tumult of the first intifada. Here, her evocative series "Women and the Veil" captured the complexities of identity and femininity.

Born in Jerusalem in 1945 to a household steeped in creativity, Tamari's artistic path was seemingly destined, shaped by the rich tapestry of her familial heritage and the tumultuous socio-political landscape of her homeland. Her mother, Margo Dabbas, and brother, Vladimir Tamari, were both artists, and her sister, Tania a classical singer. Raised amidst the perpetual specter of war and with the threat of Israeli occupation looming, Tamari found solace and resistance in art, culture, and education. Through her artistic expression, she delivered potent political messages and cultivated institutional spaces dedicated to preserving Palestinian cultural identity.

Vera’s artistic odyssey commenced with a Bachelor of Arts in Fine Arts from the Beirut College for Women in 1966, followed by immersive studies in ceramics at the Istituto Statale per la Ceramica in Florence, Italy. Her thirst for knowledge led her to Oxford University, where she obtained an MFA degree in Islamic Art and Architecture in 1984, further deepening her understanding of cultural heritage. Clay became Tamari's medium of choice to convey narratives of Palestinian identity and resilience. Establishing the first ceramics studio in the West Bank in 1975, Tamari carved her legacy as a pioneer, sculpting intricate bas-reliefs and sculptural installations that breathed life into themes of family, memories, and landscape. Her works, often utilizing the natural hue of clay juxtaposed with warm colors, evoke the resilience and rootedness of Palestinian identity. Drawing inspiration from the female form and olive trees, Tamari's sculptures encapsulate the essence of Palestinian womanhood and the enduring strength of her people.

Vladimir and Vera’s mother Marguerite Nicola Debbas, taken 1939 in Jaffa.

Tamari's artistic endeavors transcended the confines of her studio, extending into education and cultural preservation. As a lecturer at Birzeit University, she instilled a passion for art in her students, fostering critical thinking and creativity amidst the backdrop of occupation and conflict. Her leadership culminated in the establishment of the Birzeit Ethnographic and Art Museum in 2005. “Going for a Ride?” is an installation of arranged cars crushed by Israeli tanks, during the 2002 invasion of Ramallah on a piece of tarmac. From across the street Vera watched Israeli tanks stop and stare. She told the Guardian “a whole cohort of Merkavas turned up and the tank commanders got out and discussed what to do. Then they got back into their tanks and ran over the whole exhibit, over and over again, backwards and forwards, crushing it to pieces. Then, for good measure, they shelled it. Finally, they got out again and pissed on the wreckage.” Tamari recorded the act on video. For her art is not merely a medium of expression but a conduit for change. Her sculptures stand as silent sentinels of Palestinian identity, and her legacy will continue to inspire generations.

Vladimir Tamari, born in Jerusalem, embarked on a distinctive path into the art world. Educated at a Quaker institution in Ramallah, he pursued a dual passion for physics and art at the American University of Beirut. His academic journey took an international turn with a brief stint at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London, followed by the Pendle Hill School Quaker Center in Philadelphia.

Between 1966 and 1970, Tamari was based primarily in Beirut, where he was actively engaged with the plight of Palestinian refugees, collaborating with UNRWA to document their struggles through photography. His versatility extended beyond photography to graphic design, where he lent his talents in support of the burgeoning Palestinian liberation movement. Settling permanently in Japan, Tamari and his wife, Kyoko, established their home and raised a family in Kyoto and Tokyo. Immersed in the vibrant cultural milieu of Japan, Tamari pursued a multifaceted career exploring not only art but also delving into the realms of physics and industrial design.

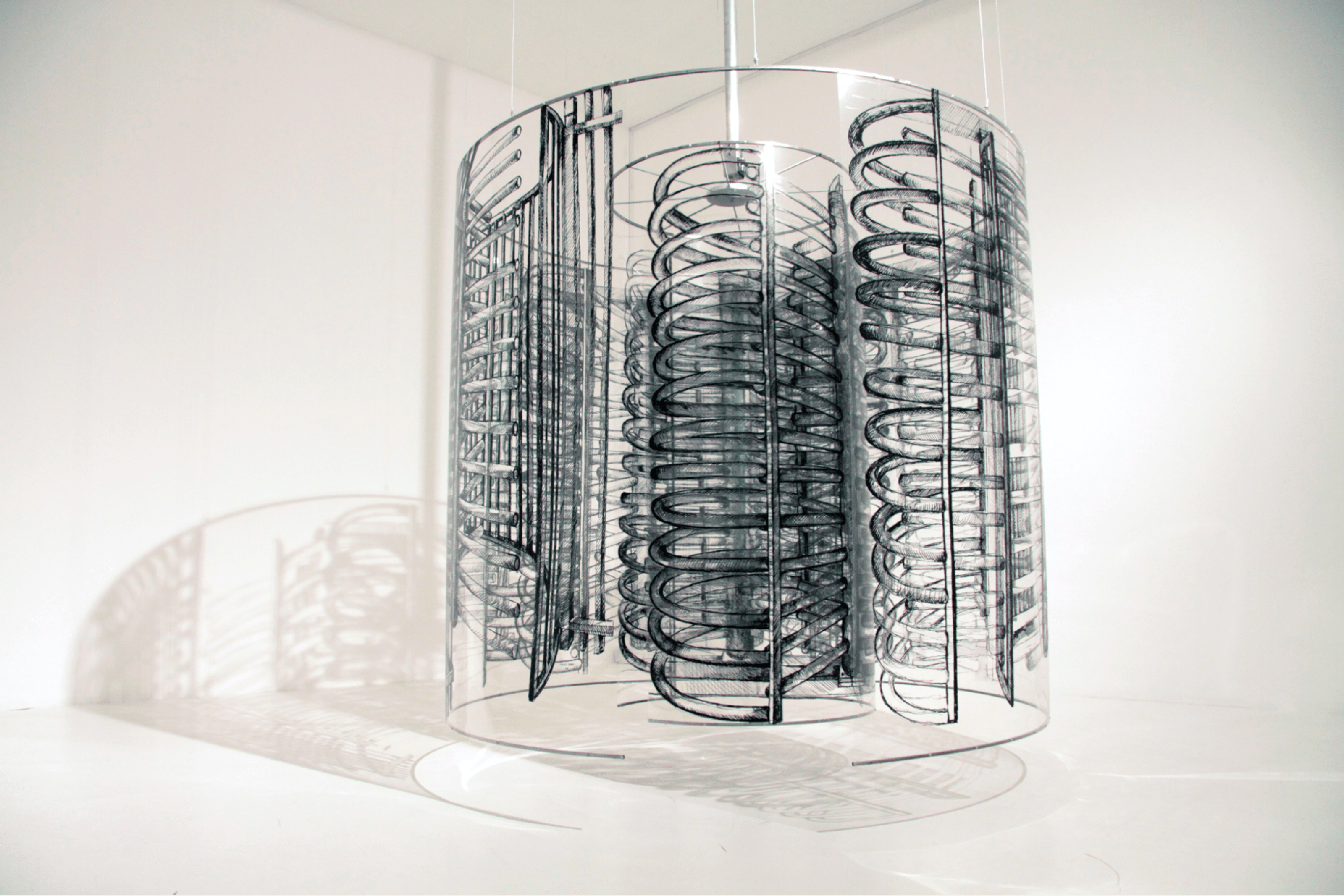

His artistic oeuvre is characterized by a captivating interplay of colors and light, reflecting the luminous essence of his Palestinian upbringing. Rooted in the rich tapestry of his cultural heritage, Tamari's artistry embodies a harmonious fusion of tradition and innovation. He also distinguished himself as an inventor, conceptualizing groundbreaking optical devices. Among his notable creations is the "3DD," an instrument that enables artists to render three-dimensional drawings in space. Despite setbacks, including the loss of his initial prototype during the upheavals of the 1967 war, Tamari persevered, dedicating years to refining and perfecting his inventions. He passed away in Tokyo in August 2017, the same day he finished his final painting, depicting a cherry blossom tree near his home.

Reflecting on his childhood in 1991, Tamari claimed that four significant influences shaped his formative years: church life, the surrounding culture of Islam, Palestinian and Arab nationalism, and “a veneer of European ‘modern’ culture and values' ' adopted by upper-class, educated Arabs. Tamari’s family belonged to the Eastern Orthodox Church, and their religious traditions brought him into contact with other cultures at a young age. His maternal grandmother facilitated visits to the Holy Land for Orthodox pilgrims from Russia, which is how the artist claimed to have come by his Russian, first name.

Fadwa Tuqan’s journey, marked by personal and political upheavals, translated into powerful verses that captured the essence of Palestinian identity and resistance. Through her poetry, Tuqan navigated themes of exile, nationalism, and feminism. In the 60’s she studied English and literature at Oxford University and found solace in the serene English countryside and the anonymity of London. This phase allowed her to explore new literary landscapes, borrowing motifs from her experiences in exile and blending them with bold expressions of sensuality. Despite the cultural distance, even her works inspired by distinctly non-Palestinian subjects, such as "Visions Of Henry," reflected a deep-seated connection to her homeland and the perennial struggle to reconcile escapism.

The 1967 Israeli occupation of Nablus marked a significant shift in Tuqan's poetry, infusing it with a more overtly nationalistic fervor. Her work began to address the grim realities of life under occupation, portraying the indignities and hardships faced by Palestinians. Poems on waiting at border crossings, the trauma of house demolitions, and the fervor of the children's uprising provided a poignant commentary on the day-to-day struggles of her people. Growing up in a conservative household, Tuqan's early life was marked by seclusion from the public eye. Despite this, she emerged as a pioneering Arab feminist, using her poetry to address women's issues and challenge societal norms. The death of her brother Ibrahim, a prominent poet and playwright, in 1941, and later her brother Namr in a plane crash in 1963, also left imprints on her work. These tragedies imbued her poetry with a deep sense of elegy and mourning. It was the translation of Tuqan's poetry into English in the 1980s catapulted her to international fame, expanding her audience beyond the Arab world. Her ability to intertwine personal grief with nationalistic fervor, and her pioneering feminist voice, have left a lasting legacy.

It's important to note that our focus on the artists in this chapter stems from their specific experiences as Palestinians in exile and the diaspora. We have not explored artists who exhibited within native Palestinian soil during this period. In the early 1970s, Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip faced cultural isolation. And yet a generation of artists that include: Karim Dabbah, Taysir Sharaf, Kamel Mughanni, Fathi Ghaben, Issam Badr Suleiman Mansour, Taysir Barakat, Fatin Tubasi, and Yusuf Duwayk emerged. In 1973, they founded the League of Palestinian Artists, marking the first collective manifestation of Palestinian art on native soil under military occupation. Works depicted landscapes scarred by conflict, the resilience of Palestinian heritage and traditions, and the enduring spirit of resistance among the people. Artists employed a variety of mediums, from traditional painting and sculpture to more experimental forms such as installations and performance art, adapting their techniques to circumvent censorship and convey their messages effectively. Despite Israeli censorship, these exhibitions became powerful acts of political resistance, held in schools, town halls, and public libraries, drawing diverse crowds and fostering community solidarity. The use of even the four colors comprising the Palestinian flag was prohibited, and attempts to establish local galleries were thwarted. Unauthorized exhibitions faced raids by troops, with audiences forced to disperse and artworks confiscated. Palestinian artists frequently endured long interrogations and arrests. Paradoxically, these harsh measures fueled an even greater sense of empowerment among the artists.

Ghaben, celebrated for his vivid portrayals of Palestinian folk life, landscapes, and the resistance succumbed to respiratory problems exacerbated by the dire medical conditions in Gaza earlier this year. His final days were marked by a struggle for breath, a tragic metaphor for the suffocation felt by many in Gaza. A video shared by a family member on February 19 depicted the artist gasping for air, repeatedly saying, “I am suffocating. I want to breathe. I want to breathe,” before being overwhelmed by a coughing fit. Despite being hospitalized at Shuhada al-Aqsa Hospital the lack of adequate medical supplies and the inability to leave Gaza for better treatment sealed his fate. Israeli authorities denied Ghaben permission to exit the Strip. His death is not only a profound loss to the Palestinian artistic community but also a reminder to the world of the hardships faced by those living under siege.

Born in 1947 in Hiribya, a village north of Gaza that was destroyed during the Nakba, Ghaben’s life was steeped in the struggles and resilience that characterize the Palestinian experience. His family’s displacement led them to the Jabaliya refugee camp, where harsh conditions curtailed his formal education at the sixth grade. Yet, Ghaben’s passion for painting persisted, even as he took on the responsibilities of adulthood at an early age. By nineteen, he was married and soon a father to eight children, juggling labor and art in a relentless quest for expression and survival.

His 1982 oil painting “Identity,” depicting a protest at the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem, was a prescient piece that anticipated the first intifada. This artwork, which was reproduced on posters distributed throughout the West Bank and Gaza Strip, drew the attention of Israeli authorities. In 1984, Ghaben was arrested and imprisoned for six months for allegedly painting the Palestinian flag. Seven of his paintings were confiscated, deemed to incite violence. Despite the oppression, Ghaben’s art thrived, imbued with what artist a Samia Halaby described as “the raw power of working-class anger.” His pieces were not marked by “decadent refinements,” but rather by a visceral connection to the lived experiences of his people. The loss of Ghaben’s home and studio to Israeli bombings further underscores the vulnerability and resilience of Palestinian artists. His works, which encapsulated decades of struggle are buried now under rubble.

In a 2008 interview with the Palestinian Chronicle, Ghaben pondered the future of his children under occupation, questioning, “How long will they suffer? We are all still trapped here inside the Gaza Strip.” This sense of entrapment and longing for freedom resonated deeply in his work, making it not just art but a cry for justice.

During the 1970s, many prominent Palestinian and non-Palestinian literary figures gathered in Beirut and worked at the PLO Research Centre and numerous Palestinian-led periodicals emerged. Most were affiliated with various factions, political parties, or unions and primarily focused on political and historical topics. In 1971, the Centre began publishing an important periodical, Shuʾun Filastiniyya, which initially focused on politics until Mahmoud Darwish became editor-in-chief in 1977, the periodical began to feature more literary content.

Shuʾun Filastiniyya published literary studies and paid special attention to both prison and folk literature. It was here that Muin Bseiso first published excerpts from his prison autobiography, "Dafatir Filastiniyya" ("Palestinian Notebooks"). Nimr Sarhan, a key scholar of Palestinian folk heritage, regularly contributed articles on folk literature. One significant contribution was Ghassan Kanafani’s study on the 1936–39 Revolt, titled "Thawrat 1936–1939 fi Filastin" ("The 1936–1939 Revolution in Palestine"). Kanafani explored the relationship between political events and literary output during periods of revolution, suggesting that the pre-Nakba period created a cultural atmosphere carrying both revolutionary and anticolonial discourse.

The periodical featured contributions from Palestinians within Israel and the occupied territories and included contributions from the diaspora, with figures like Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Edward Said, and Ibrahim Abu Lughod.

The periodical also responded to contemporary events, such as the 1976 Tel al-Zaatar massacre, with Darwish dedicating an editorial to the tragedy. During this time, Shuʾun Filastiniyya commissioned prominent artists and graphic designers in Beirut, including Kamal Boullata, Mona Saudi, Etel Adnan, Dia Azzawi, Ismail Shammout, Samia Halaby, and Jumana al-Husseini, to design its covers, blending visual art with revolutionary literature.

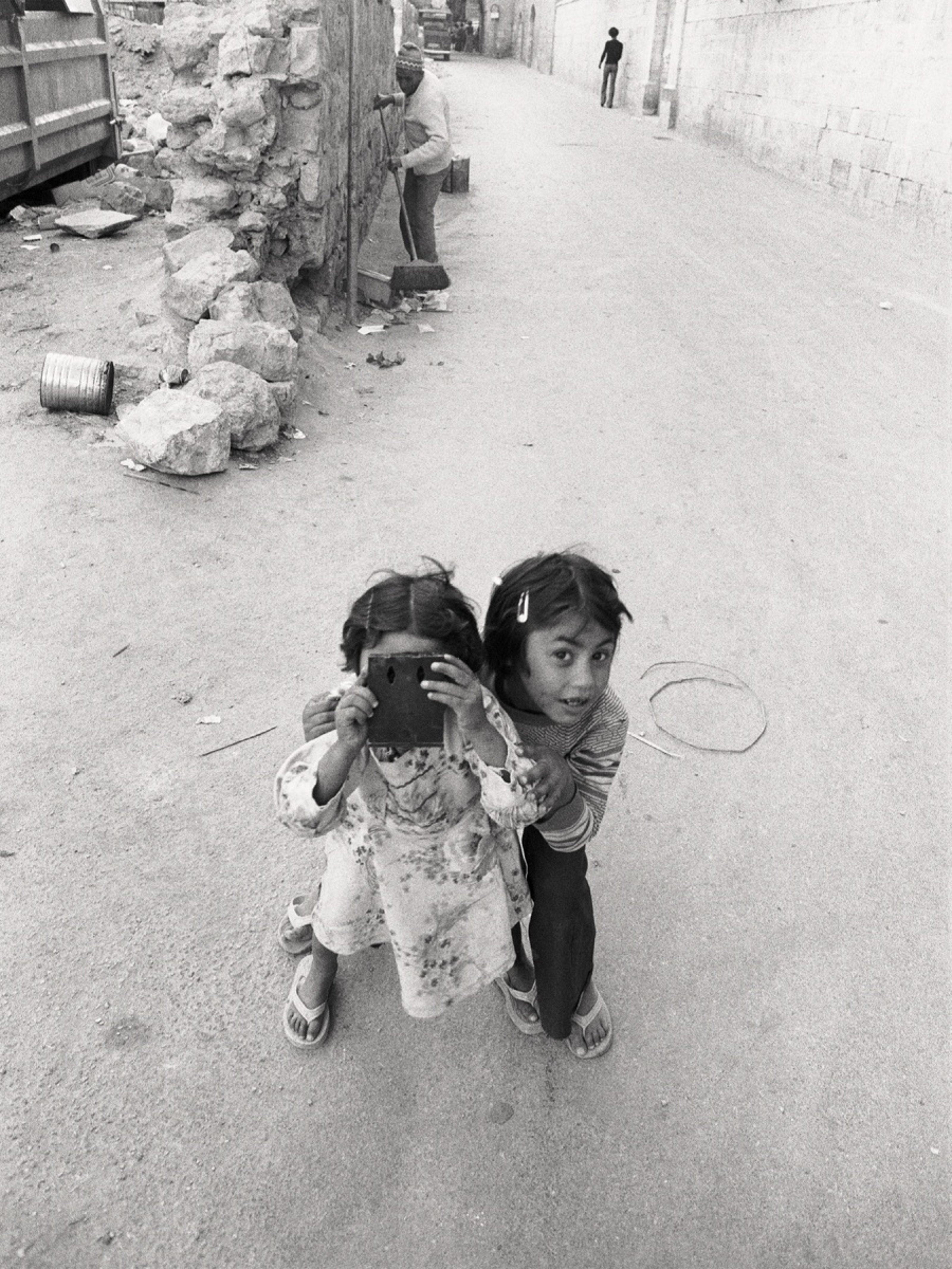

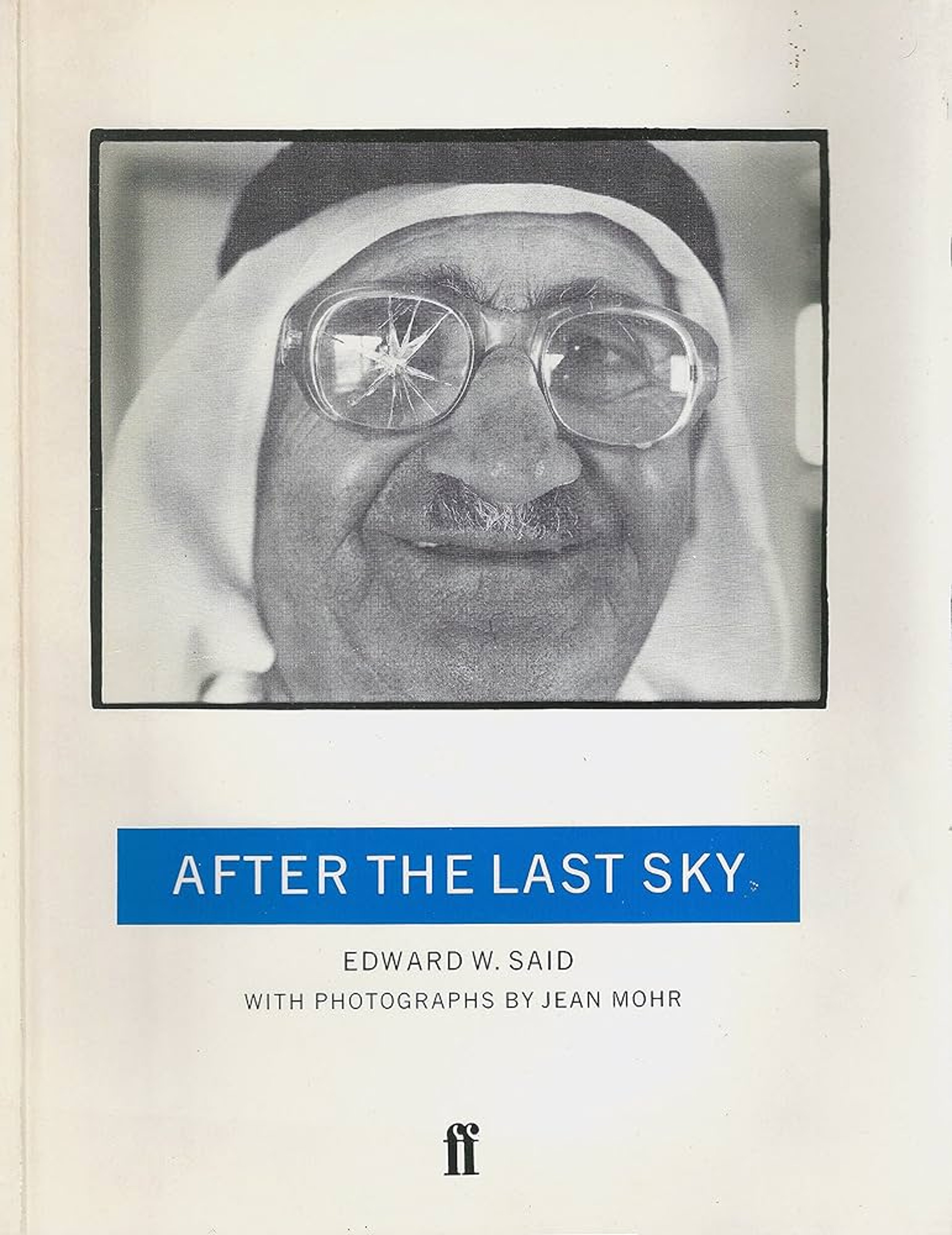

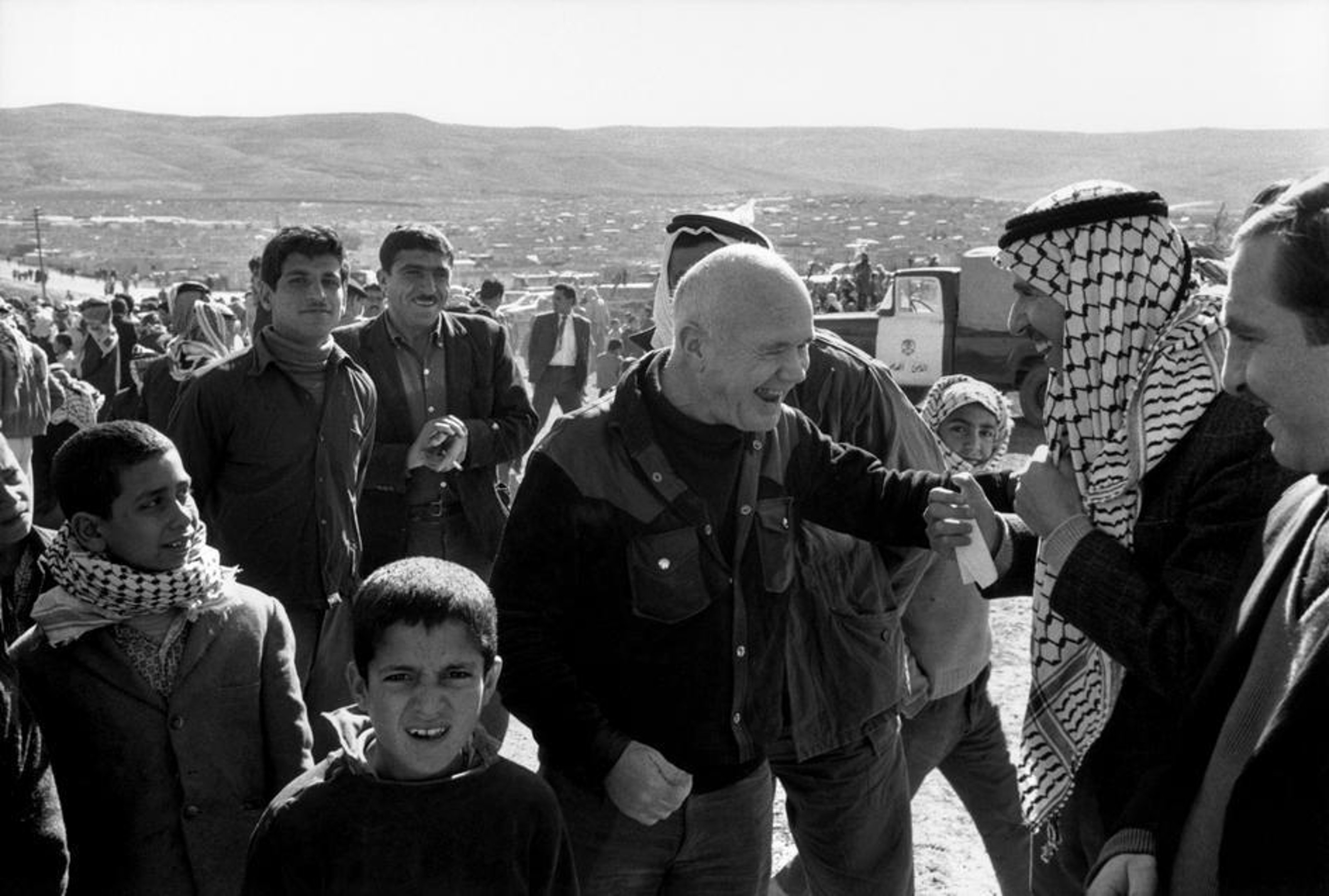

In 1983 Jean Mohr was commissioned by the UN, on Edward Said’s recommendation, to take photos of some of the key sites in which Palestinians lived their lives. Because the UN allowed only minimal text to accompany the photographs, Said and Mohr decided to work together on an 'interplay', as Said put it,– 'an unconventional, hybrid, and fragmentary [form] of expression' - which they called After the Last Sky (1986). Through the combination of Mohr’s photographs and Said’s text, the Palestinians acquire a political agency that holds viewers accountable. The collaboration was a meeting of minds that transcended the boundaries of their respective disciplines, photography, and literature. Their partnership gave birth to a profound exploration of the Palestinian experience, capturing the essence of a people struggling against oppression and displacement.

For Mohr, this mission marked the continuation of a lifelong commitment to the Palestinian cause. His initial visit to Palestine in 1949, on assignment for the ICRC, occurred just a year after Israel proclaimed independence. Witnessing the aftermath left a profound impact. This series of photographs acknowledges the tensions between insider and outsider, fiction and reality, photographer and subject; a kind of “double vision,” as Said succinctly put it. “Most people are principally aware of one culture, one setting, one home; exiles are aware of at least two,” he wrote, “and this plurality of vision gives rise to an awareness of simultaneous dimensions, an awareness that—to borrow a phrase from music—is contrapuntal.”

Throughout the book, one will notice how Palestinian homes in diaspora families decorate their homes with images from their past lives and homes. For example, one photo is taken in the house of the former mayor of Jerusalem and his wife, in exile in Jordan—one cannot but notice the huge wallpaper/poster of the old city of Jerusalem. Other photos contain objects that remind of the previous home: embroidery, a shawl, a picture, an icon, and pottery. The memory of a past home is not only constructed through narratives of past life but also through small design objects. These objects come to have resonance in the Palestinian nationalists and the refugee narrative.

On the relics that traveled with them, Said says: “These intimate mementos of a past irrevocably lost circulate among us, like the genealogies and fables of a wandering singer of tales. Photographs, dresses, objects severed from their original locale, the rituals of speech and custom: much reproduced, enlarged, thematized, embroidered, and passed around, they are strands in the webs of affiliations we Palestinians use to tie to our identity and each other.”

Jean Mohr was a Swiss photographer renowned for his poignant documentary photography that often focused on human rights issues and social justice. Born in Geneva, Mohr initially studied economics before turning to photography in the early 1950s. He collaborated extensively with various international organizations, including the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), capturing the lives and struggles of refugees and displaced persons around the world.

Mohr's work is characterized by its empathetic portrayal of marginalized communities, particularly Palestinian refugees, which he documented alongside his friend and author John Berger. Their collaborations, such as in the book "A Seventh Man" (1975), explore the lives of migrant workers and remain significant contributions to documentary photography and social commentary. "After the Last Sky," remains a testament to the enduring power of art to illuminate the human condition. Through their partnership, Mohr and Edward Said forged a connection that transcended cultural and political divides, leaving behind a legacy that continues to provoke thought to this day.

Edward Said, a scholar, writer, and intellectual, profoundly impacted the understanding of post-colonialism and cultural criticism during the 1970s and 1980s. He was born in British Mandate Palestine in 1935 and grew up between Jerusalem and Cairo. His education followed the British curriculum, giving him a firsthand understanding of colonial dynamics and a deep appreciation for Western literature. Living in exile, Said used his unique position to critique Western perceptions of the East, a theme most notably explored in his seminal work, Orientalism (1978). This book deconstructed the entrenched stereotypes and cultural narratives that Western literature and academia had historically imposed on the Eastern world. Said's critique was groundbreaking, as it challenged the intellectual underpinnings of colonialism and advocated for a more nuanced and respectful engagement with Eastern cultures. His work resonated widely, encouraging scholars to reconsider and reevaluate their approach to cultural studies and international relations.

During the 70s and 80s, Said's writings underscored the importance of culture as both a battleground and a bridge in global discourse. He believed that cultural representation and narratives were crucial in shaping political realities and identities. In his 1979 essay "Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Victims," Said acknowledged the philosophical authenticity of the Jewish homeland, while also asserting the Palestinians' right to national self-determination. He characterized Israel's founding, the displacement of Palestinian Arabs, and their subjugation in the Israeli-occupied territories as manifestations of Western-style imperialism. His emphasis on the role of culture in political resistance highlighted the power of art and literature in fostering understanding and empathy across divided societies. Said's contributions during this period were not only academic but also personal, reflecting his experiences in exile and his enduring commitment to Palestinian rights and humanistic values. Through his work, Said illuminated the centrality of culture in the struggle for liberation and justice, influencing a generation of thinkers and activists.

"Prisoner of Love," is a culmination of Jean Genet's observations and reflections from the time he spent with Palestinian fighters and leaders, including his experiences in Jordan and Lebanon. Genet's narrative blends memoir, reportage, and poetic meditation to provide a nuanced portrayal of the Palestinian struggle. Moving beyond the simplistic binary of victim and oppressor, Genet highlights the complexities of resistance, identity, and displacement. This approach humanizes the Palestinian fighters and situates their struggle within a broader context of liberation. He draws parallels between the Palestinian cause and other liberation movements, particularly the Black Panthers. This intersectional approach emphasizes the global nature of the fight against oppression and has inspired activists to see their struggles as interconnected.

"Prisoner of Love" is significant for being one of the first affirmations that queerness and a commitment to Palestinian liberation could not just exist side-by-side but were intricately intertwined. Writing intimately and passionately from a queer perspective, Genet highlights the intersection of sexuality and politics, broadening the discourse on liberation movements to include diverse identities and experiences. His bond with the Palestinians was an "irrational affinity," driven by an emotional, perhaps intuitive, and sensual attraction. He described his fascination with the Palestinian hijacking of civilian airliners and his subsequent enthrallment with the fedayeen in Jordan, whom he viewed as a materialization of his fantasies. This eroticized perspective adds a unique dimension to his depiction of the Palestinian struggle.

"Prisoner of Love" remains a seminal work in literary discourse. Its cultural impact extends far beyond its initial publication, continuing to inspire and influence artists. It was written at a time of grief in the Palestine liberation movement, (in the shadow of the massacres of Sabra and Chatila and the Israeli invasion of Lebanon). His vivid descriptions and symbolic imagery have inspired artists to explore themes of exile and identity. Movies like Elia Suleiman's "Divine Intervention" and Annemarie Jacir's "When I Saw You" echo the existential and political questions raised in "Prisoner of Love," exploring the lived experiences of Palestinians through a Genet-like lens of poignancy.

Born in 1910, Jean Genet had a tumultuous early life marked by frequent run-ins with the law. By the age of 17, he had been arrested eight times for offenses ranging from running away to stealing pens. Sentenced to two years at an agricultural prison for juveniles, Genet eventually joined the army and was transferred to Syria. The Arab world offered him an escape from the pain of France, becoming a place of indulgence, and a kind of romance. Here he found male beauty, ancient cultures, and intoxicating aesthetics that deeply influenced his later work. This early exposure to the Arab world laid the foundation for his lifelong fascination and connection with the region.

Jean Genet's in person visit to the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps following the massacre of September 1982, underscored his deep commitment to political activism and human rights advocacy. His presence served as a powerful call for international attention. His work "4 Hours in Shatila" implicates political powers for their roles in the atrocity, aligning his narrative with broader calls for justice by weaving personal reflections with stark descriptions of the shocking and haunting scenes he encountered.

Rebel, thief, playwright, novelist, creative revolutionary, and artistic outlaw, Jean Genet was labeled many things by many people until his death in 1986. Simone de Beauvoir famously called him a "thug of genius." At the age of 64, Genet met his last lover, Mohammed El Katranai, in Tangiers. They lived together in a small apartment in the Saint Denis suburb of Paris. On April 15, 1986, Genet died at the age of 76. He was buried in Morocco and "Prisoner of Love," a culmination of his reflections and experiences with Palestinian fighters and leaders, was published one month later. Genet "preferred to think that the Arab world should be Palestinized rather than the Palestinian revolution should be Arabized." To Genet, the only positive vision of the future should be socialist, not theological. His analysis of the failure of Zionism was that it had begun as a socialist experiment but had degenerated quickly into a theological state.

Until the 1970s, the West and Israel fought hard to erase the idea of ‘Palestine’ from the lexicon. When I was in Europe, I heard from everyone that there’s no such thing as Palestine. They are pouring immense amounts of money and effort into trying to marginalize our art. A society is measured by two things: its culture and its art. Where else can you find such accomplished art and artists who have had war waged against them for 70 years? It’s a unique story. I advise the next generation to keep being proud to be Palestinian. I don’t care what they do or how it’s connected to the occupation, and it doesn’t matter. It’s enough to have the phrase ‘Palestinian artist’ in your work whether it’s about love, music, or anything else that isn’t about the occupation. That’s already a remarkable victory against those who are trying to erase us.”

— Filmmaker Hany Abu Assad

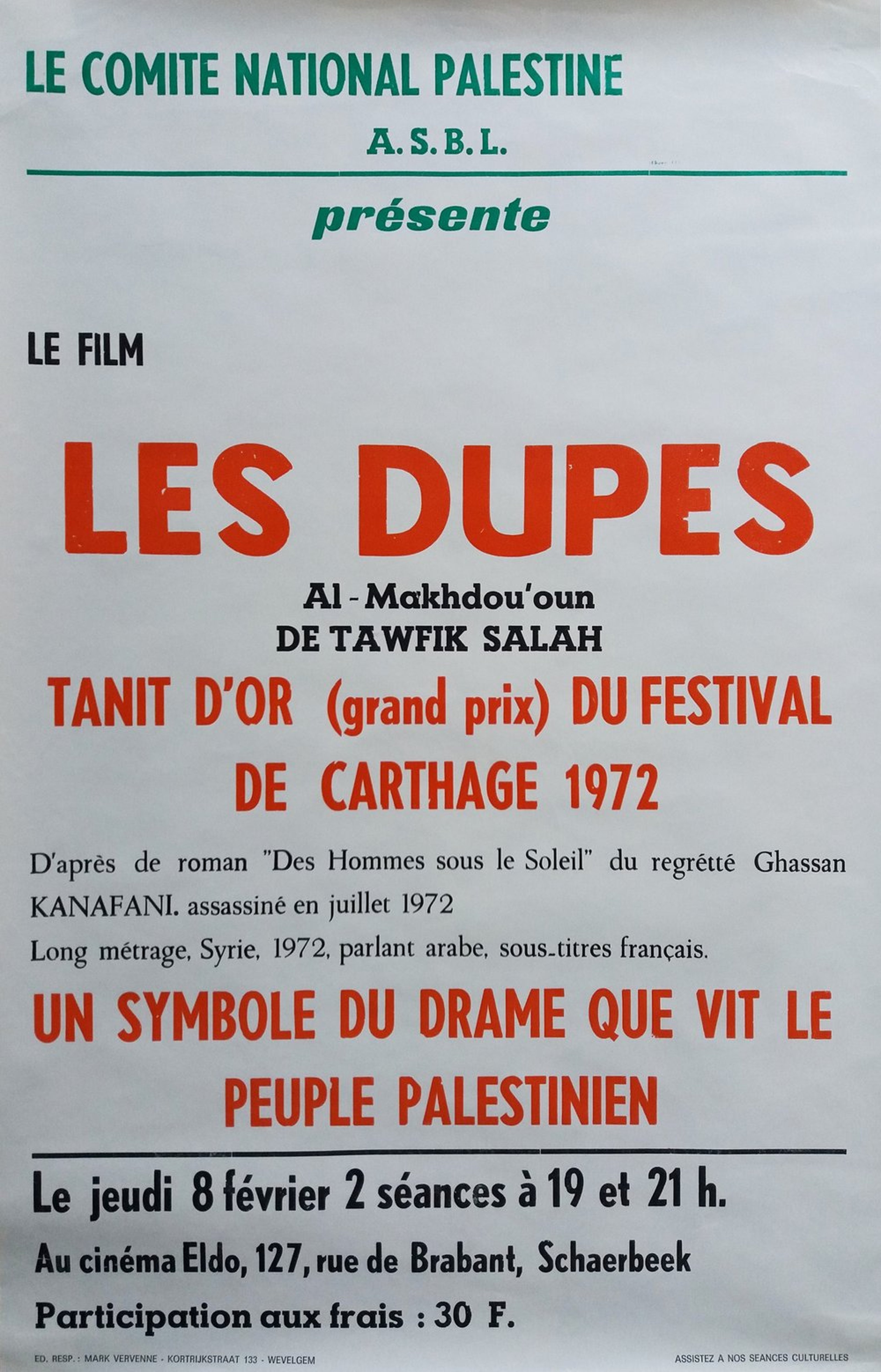

It was in 1972, that the Arabic film, Al-Makhdu’un by Tawfiq Saleh, tackled the plight of Palestinian refugees. The 110-minute black-and-white film is set in 1958, following three Palestinians in Basra, Iraq, who decide to travel to Kuwait, each believing he can make a new life for himself there. The three men, from different generations, represent varying perspectives on the Palestinian experience in the diaspora. The Dupes is based on the 1962 novella Men in the Sun, written by Ghassan Kanafani.

Through its portrayal of Palestinian characters grappling with impossible choices, the film sheds light on the psychological and sociopolitical complexities of living in the diaspora. By weaving together the personal narratives of individuals caught in the grip of colonialism, the film invites viewers to confront the harsh realities faced by oppressed peoples and the universal desire for dignity and liberation. The Dupes serves as a reminder of cinema’s potential to incite social change and foster cross-cultural empathy. By amplifying Palestinian voices and challenging narratives, the film contributes to broader movements advocating for human rights. It highlights the role of art in documenting the struggles of diasporic communities and preserving their cultural heritage.

Egyptian director Saleh, born in Alexandria in 1926, led a tumultuous career in political cinema. Interested in Arab literature, he obtained a bachelor's degree before moving to Paris in 1950 to study cinema. Returning to Egypt, he directed his first feature, Fools’ Alley (Darb al-mahabil), in 1955 in collaboration with prominent writer Naguib Mahfouz. The film's critique of materialism defined Saleh's dedication to voicing leftist revolutionary ideas. Active from 1955 to 1980, Saleh worked in various Arab countries, including Syria and Iraq, maintaining a committed thematic focus on the Palestinian cause, earning him the nickname "Sinbad of Arab Cinema." Saleh believed cinema should incite a desire for dismantling unjust realities by bringing narratives of struggle to life. His filmography remains a testament to the power of cinema as a tool for change, rather than a means to distort reality or provide escapist entertainment.

In 1970, Jean-Luc Godard, alongside Jean-Pierre Gorin and the Dziga Vertov Group, was commissioned by Al Fatah, the militant Palestinian group, to shoot a documentary. Production was halted when many of the Palestinians they were filming were killed during the Black September conflict. Years after the disintegration of the Dziga Vertov Group, Godard, with his new collaborator Anne-Marie Miéville, re-edited this footage into "Here and Elsewhere." This cinematic essay is an influential work that blends documentary footage with critical commentary, reflecting Godard's evolving approach to political cinema.

Godard and Miéville intersperse scenes of Palestinian fighters with footage of a French working-class family watching television, reflecting on the disparity between revolutionary aspirations and everyday reality. This technique challenges viewers to question the ways in which the media shapes their understanding of political struggles. Their critical perspective questions the effectiveness of revolutionary images and propaganda, suggesting that they can be co-opted and lose their radical potential. By revisiting the original footage "Here and Elsewhere" addresses the gap between the revolutionary ideal and the harsh realities faced by the Palestinian people. The film’s title itself implies a dual perspective, suggesting that the struggle of Palestinians ("Here") is interconnected with broader global issues ("Elsewhere"). This reflects Godard's political philosophy, which sees individual struggles as part of a larger, interconnected web of oppression including the Spanish Civil War, Pinochet’s coup in Chile, and British imperialism in Ireland, creating a broader critique of how media represents revolutionary struggles.

The film's radical approach to documentary filmmaking has influenced numerous directors and remains a significant reference point for those interested in the intersections of cinema, politics, and media theory.

Its engagement with the Palestinian cause continues to resonate, highlighting the ongoing relevance of Godard's critique of media representation. By challenging viewers to think critically about the images they consume, "Here and Elsewhere" encourages a more nuanced and informed understanding of political struggles.

"The Palestinians" (De Palestijnen, 1975) stands as a poignant exploration of the historical and contemporary dimensions of the conflict, delving into its roots. Johan van der Keuken meticulously documents the lived experiences of Palestinians, capturing their struggles and resilience. The film captures the aftermath of the 1967 Six-Day War and the ongoing displacement and occupation faced by the Palestinian people. Through interviews, and on-the-ground footage, he presents a comprehensive portrayal of the political and social landscape of the time. From refugee camps to occupied territories, the documentary portrays the multifaceted nature of Palestinian identity. While he supports the idea of a Jewish state, the documentary carefully highlights its mercenary implications and the unjust distortion of the Palestinian cause. It underscores that the goal of the Palestinian movement has never been the annihilation of Jews but rather the pursuit of peaceful coexistence on equal terms.

Johan van der Keuken (1938-2001) was a filmmaker, photographer, and writer whose work is celebrated for its depth, sensitivity, and innovative style. Over his career, van der Keuken created numerous documentaries that examined social, political, and cultural issues, often blending personal narratives with broader historical contexts. His ability to humanize complex subjects and present them with visual poetry has left a lasting impact on the documentary genre.

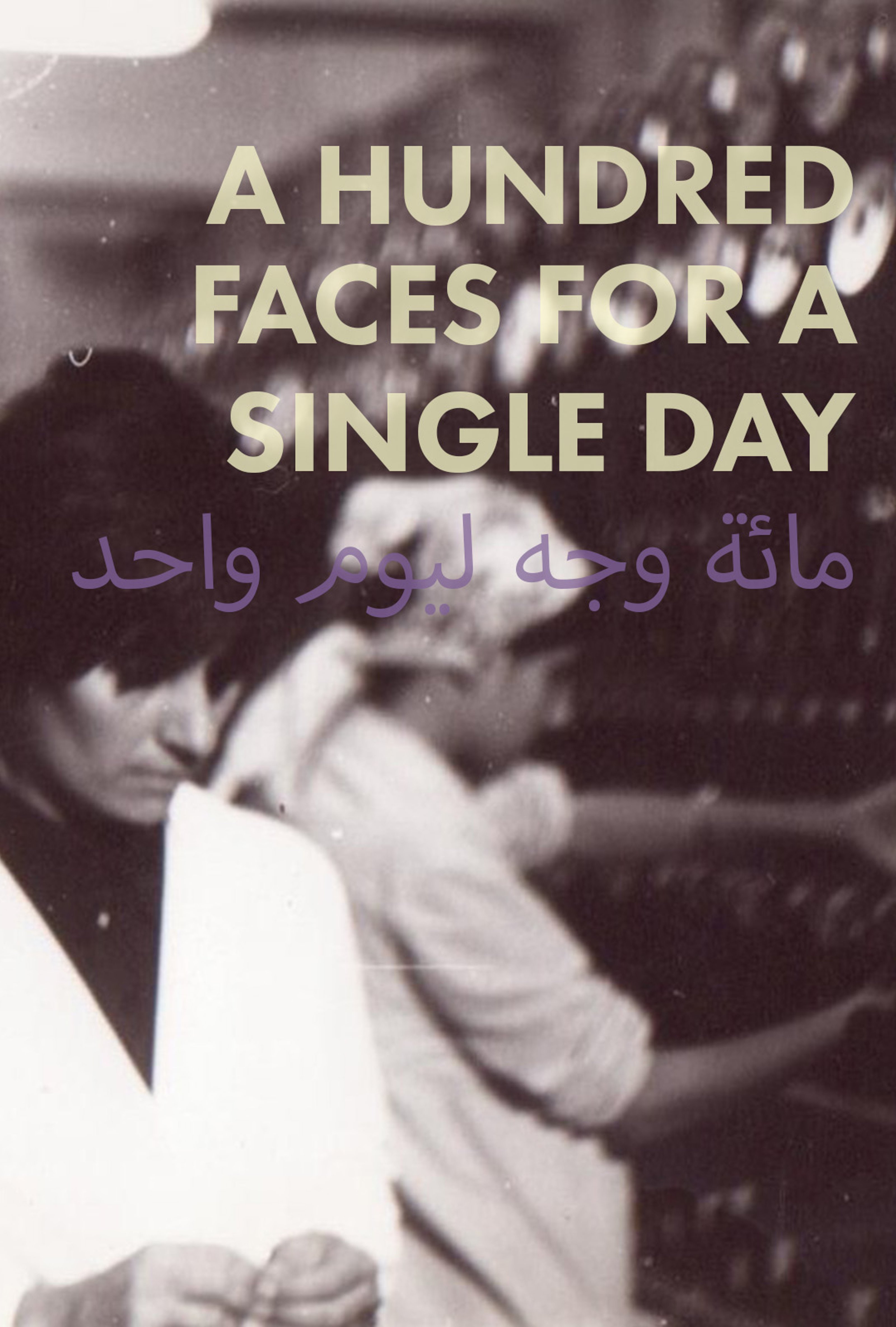

Released in 1972, "A Hundred Faces for a Single Day" stands as a monumental achievement in Lebanese cinema, directed by Christian Ghazi. This film boldly confronts themes of identity within the backdrop of the Palestinian struggle. Through its innovative narrative structure and subject matter, the film not only captures historical moments but also challenges conventional storytelling. At its core, "A Hundred Faces for a Single Day" presents a tapestry of Palestinian life under occupation, intricately woven through a series of vignettes. They serve as windows into the daily lives, struggles, and aspirations of individuals grappling with harsh realities and highlights the resilience of the Palestinian spirit, portraying a populace that persists in preserving its cultural heritage. Through a blend of realism and moments of beauty, Ghazi captures both the brutality of occupation and the moments of human connection and hope that transcend it. The use of experimental sound design enhances the film's immersive experience, drawing viewers deeper into the emotional landscape of its characters and their collective struggle.

Thematically, it serves as a critique of bourgeois decadence and political hypocrisy in Beirut during a pivotal era of the Palestinian revolution. Ghazi's narrative approach, characterized by overlapping storylines and abstract sequences, offers a visceral portrayal of societal tensions and the transformative power of resistance movements. By embracing experimental techniques and pushing the boundaries of storytelling Ghazi crafted a visually compelling call to action for social change.