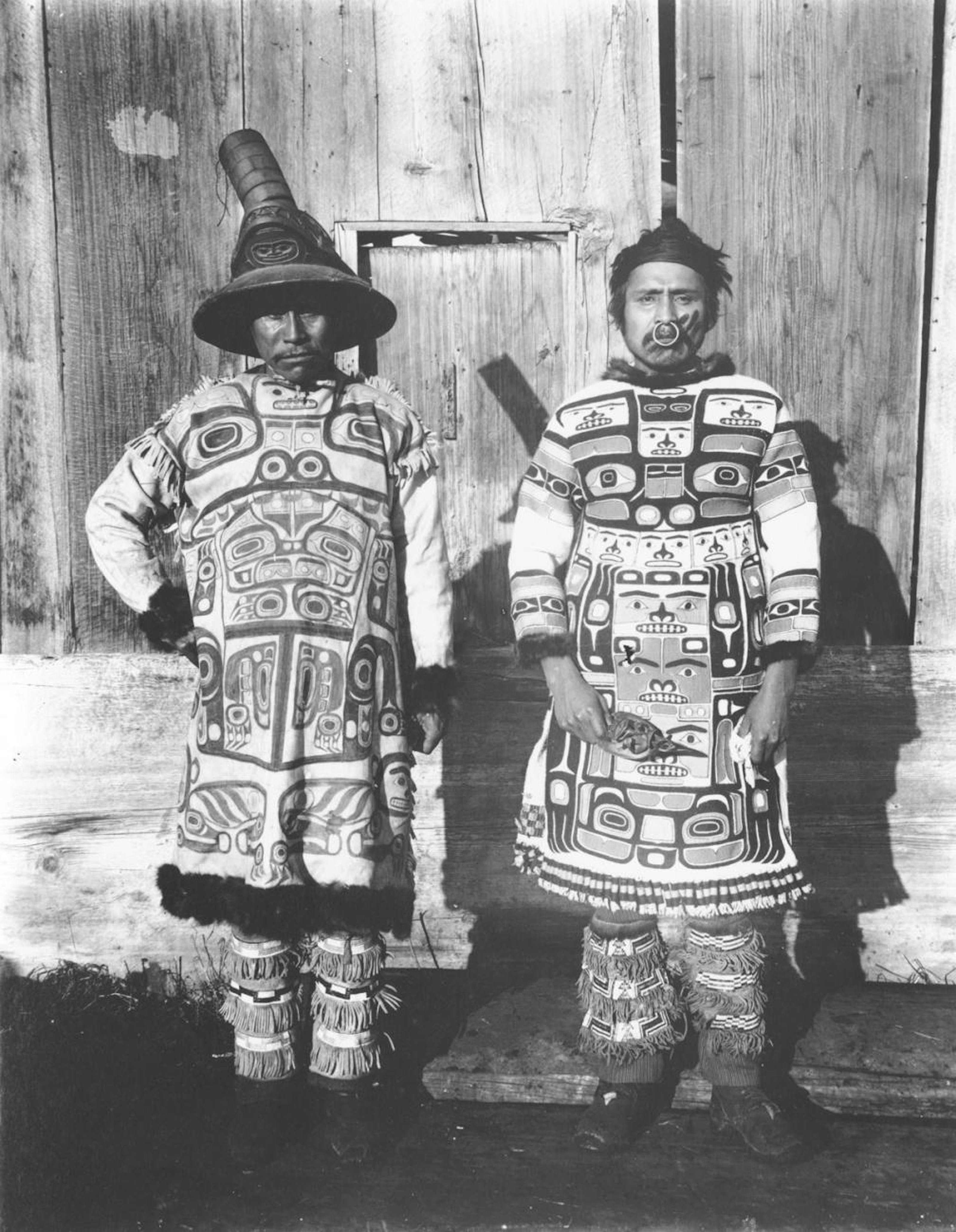

Imagine your hats, tunics, jewelry, and even instruments told your family’s story. Each ancestor who owned these pieces marked them through painting or carving, meaning they held great significance to you and your family. They were made under special circumstances surrounding your ancestors’ life: they required great technical skill to make, and only certain stories documented on the clothing could be told by specific family members. You and the other living relatives pulled these items out for special occasions, such as marriages, holidays, large family gatherings, funeral ceremonies, and other cultural and spiritual celebrations. Losing them would be like losing a member of your family.

One day, people you had never seen or met showed up at your house. They asked questions: “What do these drawings on your hat mean? Where did you source the materials? Can you show us where and how to source them? Who do you worship with these rattles?” The questions felt intimate and inappropriate for strangers to ask. One day, these strangers forced their way into your house and stole your family’s regalia. You were never told where they took it or why they needed it.

These people who had stolen your clothes moved into your town and stayed there, changing the landscape around you and your entire way of life. They erected huge buildings and monuments to people completely irrelevant to you, or who had organized the theft of your possessions. Years later, curiosity got the best of you, and you decided to visit one of these large, gaudy buildings to learn what these interlopers might hold dear as a cultural value. The objects inside the building were housed behind plexiglass walls and seemed to come from groups of people similar to you: clothing, boxes, and utensils bearing illustrations and carvings that told a family’s history of love, war, conquest, agony, and triumph. That’s when you spotted them—your hat, your tunic, your whistles! Surely this was a mistake. Brutal thieves had stolen your family heirlooms; if someone had found them, they would return them to you… right?

Chilkat Chiefs in Dancing Costumes, Alaska. ca. 1895. Alaska State Library, Winter and Pond. Photographs, 1893-1943. ASL-PCA-117, Image ID No: ASL-P117-172

This is a true story based on the return of various objects from the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C. to the Tlingit Nation in southeast Alaska.1 Though the Tlingit received back many items stolen in the 1800s, other colonized groups around the world have stories similar to this one, yet have not seen the stolen items returned to them. The question of repatriation might seem obvious to some. Still, the thought of returning an item from a Western cultural institution to the group it originally belonged to did not gain mainstream attention until the 1950s, after the horrors of colonization and war were made apparent during the trials after World War II. During the occupation, Nazis plundered Polish and Jewish properties, dispossessing them of financial assets that included artworks.2 After the war, powerful cultural institutions in the West had to come to terms with the fact that they also capitalized off the dispossession of millions of Indigenous peoples around the world and cooperated with settler-colonial governments who plundered sacred objects and assets. Considering these parallels, one might assume that institutions are clamoring to return the stolen objects in their collections.

Monogrammist AT, ‘St Dorothy with the Christ Child’. Paper, Germany, c.1467–1470. © The Trustees of the British Museum

But even in 2022, this isn’t the case. The argument for repatriation is a relatively new one. The truth is dispossession is not neat and tidy: many plunderers did not take care to note whose items they were stealing while they were committing acts of violence. As such, it is not always easy to know to whom an artwork or cultural object should be returned. In the 1990s, the term “decolonization” became more prevalent on Western scholars’ tongues and pens, and institutions including the notorious British Museum formed committees that continue to trace the provenance of artworks in their holdings.3 For now, many of these committees trace objects and artworks primarily stolen during Nazi occupations instead of those stolen through colonial occupations or military coercion. But a turning point emerged in 2018 when in the ongoing case of the Elgin Marbles at the British Museum brought “repatriation” into the mainstream.4 Greece has been asking for their return since 1832, and four years ago a British politician committed to returning the marbles if he were elected Prime Minister, sparking heated debate about the ease with which a country can return precious stolen artifacts.5 However, British law prohibits museums from returning objects in public collections.6

An example of how archaic laws prohibit the return of stolen artifacts is the case of the Asante gold artifacts at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. These were looted by British forces from the city of Kumasi in 1874, and although the V&A Museum’s director, Tristram Hunt, seems set on returning the objects, he is prohibited from deaccessioning them due to a 1983 British law that states that national British institutions may not export any objects in their permanent collections, even in the case of cultural repatriation.7

Asante goldweight in form of cartridge belt, late 19th century, Ghana. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In the case of the Tlingit Nation, even when repatriation was possible, it happened very slowly: the NMAI returned 73 objects to them over twenty years, only processing the last of the claims the Tlingit sent to them between 1998 and 2015 in 2019. Though cases of repatriation should not be rushed for fear of a catastrophic blunder, it is clear that institutional bureaucracy is often used as a tool to prevent objects from leaving a museum collection.

Successful cases of repatriation are seen by some as a symbolic fall of the Western world—or at least that the hierarchies of knowledge with European Enlightenment-cultivated knowledge on top may be coming to an end. If the West is no longer seen as the keeper and teller of global knowledge, then the validity of an institution like a museum disappears with it. For example, the Benin Bronzes are a collection of thousands of objects stolen from Benin, Nigeria, that have been spread across institutions such as the British Museum in London, the Ethnological Museum in Berlin, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, among others.8 German cultural officials have publicly stated they are committed to returning the Benin Bronzes that are housed in Germany. Still, there are repatriation skeptics who seem to believe Nigeria doesn’t have the conservation capacity to care for these objects. This interminable process reveals how Western institutions value the academic study of objects and the “other” over the points of view of those who created these “exotic” objects. What is at stake in repatriation is the failure of Western epistemology. Returning these objects would tacitly admit that Western hegemony is not the only valid way of understanding the world—or preserving it.

This might be why the Elgin marbles are a famous example of repatriation—named after the 7th Earl of Elgin who instructed their removal from the Parthenon and subsequent transfer to England, the symbols of power, history, and empire, shifted to London. Spoliation has long been used in war as a symbolic victory by looting objects of power and bringing them to the capital of the winner—such as the Egyptian obelisks that still stand in Rome. The Earl cited permission from the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire—the ruler of the territory at the time—as his authority to remove the statues. In 1816, Elgin sold them to the British Government, and the government turned them over to the British Museum to care for them indefinitely.

The Parthenon Sculptures, British Museum. Photography by Carole Raddato

But unlike the Benin bronzes or Tlingit regalia, the Elgin marbles do not contain the same relation to “otherness” while they stand in the British Museum. Classical Greek sculpture, whose true history is varied and whose style was influenced by Egyptian and Near Eastern monumental art, is perceived as evidence that “Western” civilization is “the” great civilization. Nazis and other forms of white supremacy groups looked to the colossal, idealized bodies in Greek sculptures to fabricate a “historic ethnicity” that idealized the Aryan body they perceived present in the unpainted, white marble.9 And so, for these sculptures to be rightfully returned to their country of origin would mean that they are not a part of the system that upholds hegemonic institutions such as the museum and the museum collection because they do not belong there.

As increasingly complicated cases of repatriation continue to garner mainstream attention, we at Collecteurs see it as necessary to provide additional background through earlier cases of repatriation to understand why an ethics of collecting is so important in our current age. Adhering to the recently published Code of Conduct for Contemporary Art Collectors by the collective Ethics of Collecting, we will cover stories about repatriation and cultural returns as they arise, and look back to earlier cases to provide insight and in-depth remarks about moments of justice, reckoning, and insurgency that shape how we create and collect in the present. We’ll also take stock of how the art market benefits from the normalization of theft and how artists and collectors are impacted by these stories and by the possibility of fundamental change in the art world.

And as contemporary artists continue to challenge how we perceive and contextualize art in a global world, so too do cases of repatriation. Artists like Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles highlight how the museum is a site of tension between history education and the rights of people to whom history belongs. The artists scanned a famous bust of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti housed in the Neues Museum in Berlin without the institution’s permission, then turned it into a widely accessible file that can be 3D rendered, meaning anyone with access to a 3D printer could create and own a copy of Nefertiti’s head. In 2015, the artists brought several 3D scanned Nefertiti heads to Cairo, where German excavators had taken them over a century prior. Egypt has been asking for the sculpture’s return since its unveiling in Berlin in 1924, but Germany has repeatedly refused.10 In an age where information is easily accessible in digital form, what possible claims could a foreign institution have to continue to possess an object with clear violations in its provenance? How can we redefine ownership and cultural property, and the archaic laws that govern them, through the examination of cases of repatriation and the artists who analyze them?