The Neuer Deutscher Film (New German Cinema) was a cinematic movement that originated in 1960 and was highly influenced by the French New Wave. It was about making art house films with low budgets and among its directors, two Werners – Herzog and Fassbinder – are perhaps the most noteworthy. Fassbinder, whose career was as short as it was prolific, directed avant-garde movies to melodramas and some larger international productions. Even when he stepped into Hollywood, he managed to remain faithful to the concepts and manifesto lying behind the New German Cinema, therefore focusing on the artistic – and not the commercial – aspect of filmmaking. Fassbinder was partly responsible for putting Germany back on screen through a refreshed perspective after years of escapist productions following the Nazi regime productions.

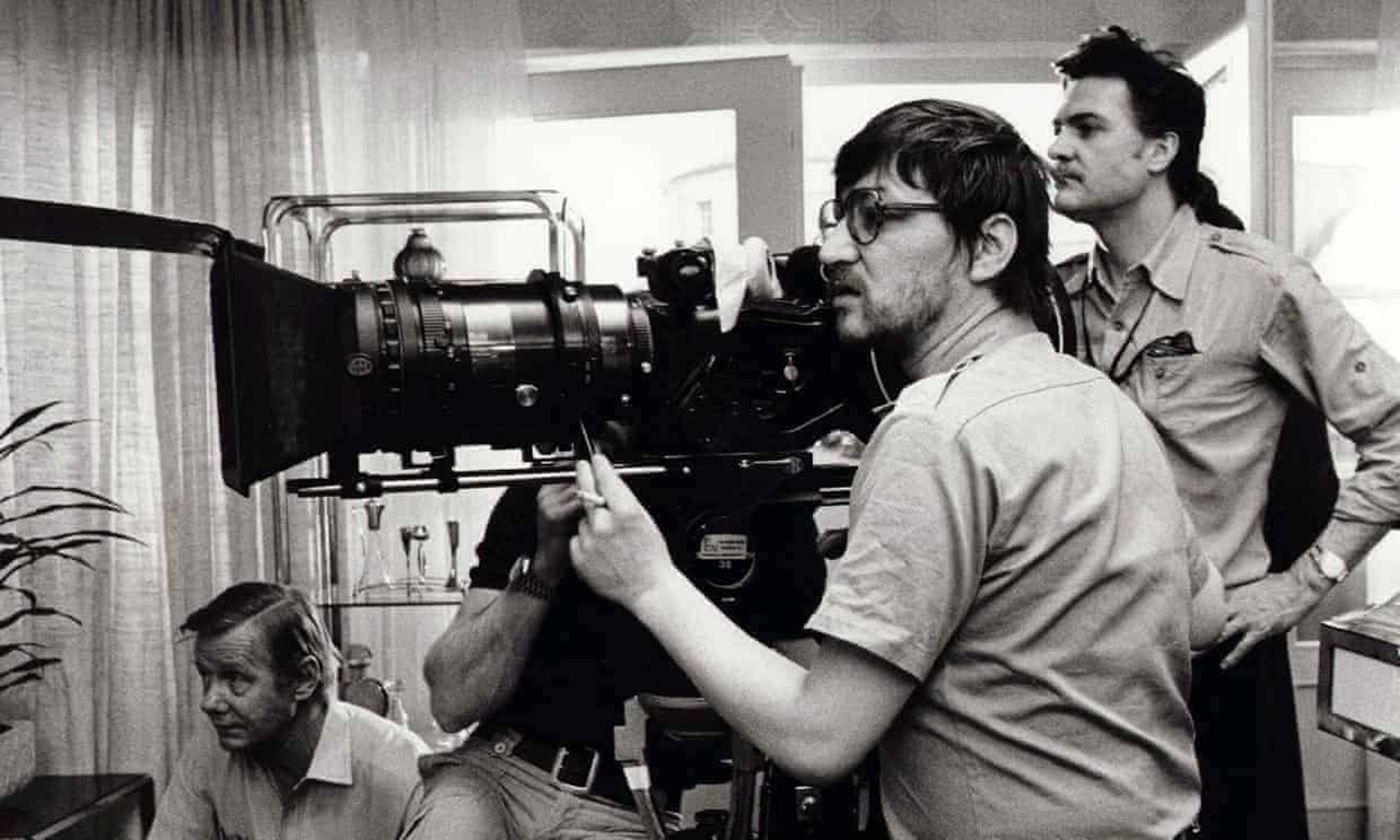

Fassbinder on set World on a Wire (1973)

Leaving behind a legacy that included over 40 films and series, Fassbinder died in 1982 when he was only 37 years old. A talented explorer of human nature, he was also way ahead of his time as is clear in World on a Wire, one of his most exceptional – and until recently – unknown works.

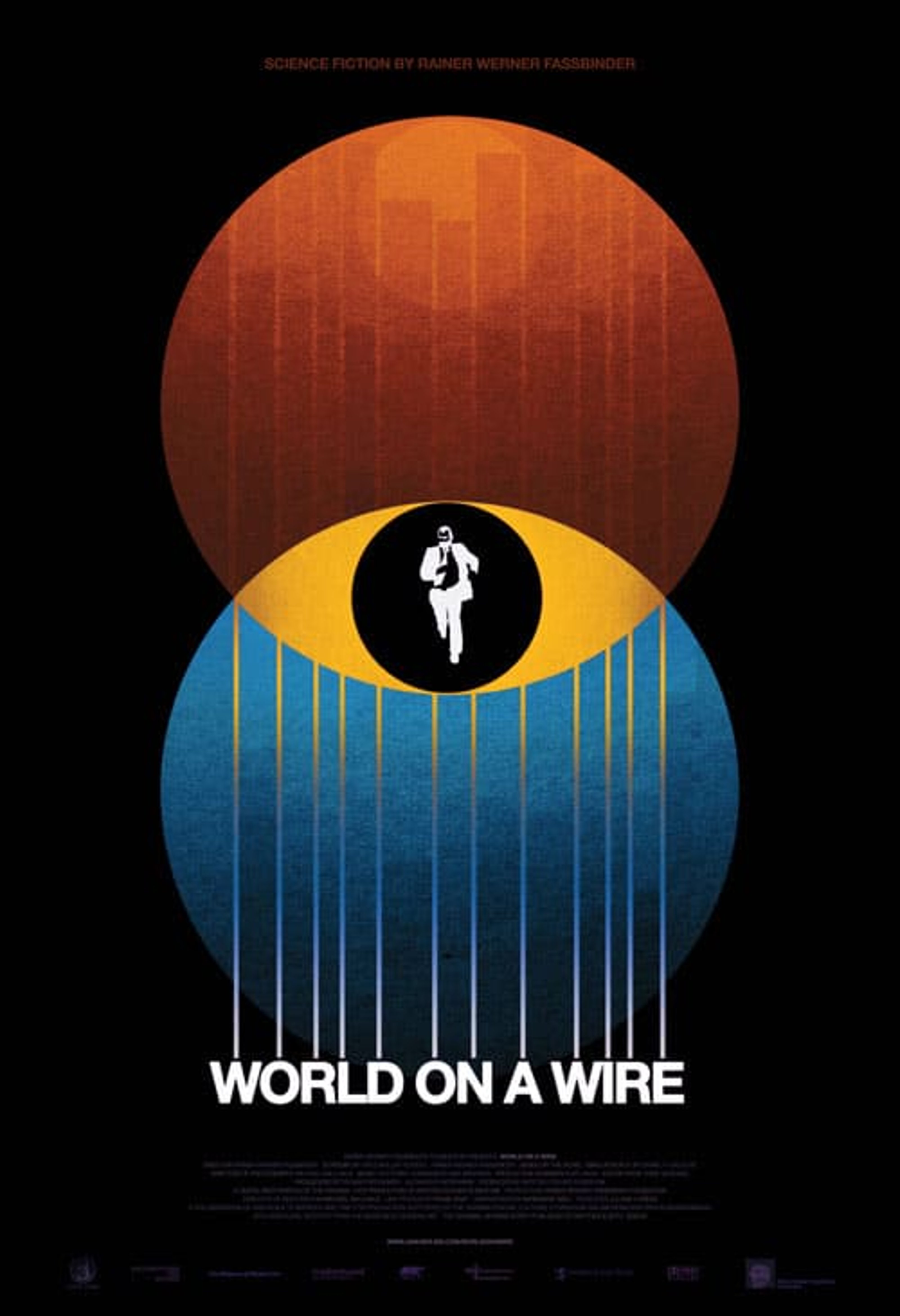

World on A Wire, his only sci-fi film, was inspired by Daniel F. Galouye’s novel Simulacron-3 and was originally conceived as a television miniseries. With a style that resembles that of Alphaville by Godard, and as relevant as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, it managed to predict today’s techniques of simulation 44 years ago.

The film tells the story of a scientist – Fred Stiller – that inherits the job of his predecessor, Professor Wollmer, who has recently died under strange circumstances. Stiller becomes in charge of a computer project called “Simulacron”, which consists of an artificial world, or mini-universe as they call it, inhabited by carefully programmed human-like beings. The main purpose of the supercomputer Simulacron is to predict what will take place 20 years later, and it does so by means of small impulses that make the inhabitants of the mini-universe react like human beings would. This way, the company behind the Simulacron, IKZ, is able to learn about future consumer habits, changes in transportation, housing, etc. The conflicting interests and the different uses that could be given to this oracular machine are what trigger an intriguing plot in which the main character ends up being persecuted both by those around him as well as by his own self.

`

`

Perhaps the most outstanding trait of the dystopian World in a Wire is the way in which it explores existence. When Stiller discovers that he is not “real”, but actually one of those artificial beings, “nothing but a bundle of electronic circuits”, he embarks on a paranoid and deeply existentialist journey motivated by a Cogito Ergo Sum proposition. Although, paradoxically, Stiller has thought and therefore discovered that he actually isn’t and Fassbinder portrays this character’s quest of meaning in a masterful way. This three-hour long, sometimes suffocating, yet unquestionably prophetic journey tells us much not only about the unknown consequences of pushing the margins of reality, but also about some of the deepest human fears and desires.