Art’s relationship to radical politics is more fraught than many people think. Making art directly serve revolution is old fashioned. In many instances, this reduces art to propaganda. And there’s no guarantee that the aims of any revolutionary movement, past or present, match up with reality or turn out the way people imagined them in the beginning. Radical, politically informed art can be a way to tell and hear the stories of people who have been silenced, or question how they have been represented by those in power. This problem runs through the recent work of British-Tamil artist Christopher Kulendran Thomas in his recent video works Being Human (2019/22) and The Finesse (2022), which address the conditions under which Tamil stories can be heard or made visible, and who gets to decide on this.

Installation views. Image courtesy of KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin.

These works appear in the exhibition “Another World” held simultaneously at the Institute for Contemporary Art in London and the KW Institute in Berlin, and produced in collaboration with curator, filmmaker, and producer Annika Kuhlmann. “Another World” reflects on two things: one is the defeat of the Tamil Revolution by the Sri Lankan government after the twenty-six year long civil war that ended in 2009; the other is how today’s quite different technological conditions might allow us to reimagine that history and think about what is still to come. It specifically focuses on the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eeelam (LTTE, better known as the “Tamil Tigers”) - the revolutionary socialist group made up of Sri Lanka’s Tamil minority who challenged the Sinhalese-dominated Sri Lankan government with the goal of achieving national sovereignty in the north of the country.

Image courtesy of Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.

The Finesse takes up the entirety of the ICA’s Lower Gallery, and reflects on the question of what revolutionary art is or can be. Drawings and sculptures form part of the piece creating an installation around two screens. One consists of five cuboid-shaped panels on LED screens, three of which are more prominent than the other two. This is placed opposite a large projection that spans the Lower Gallery. Some of its elements are filmed while others are algorithmically generated and thus always show current news using a technique that we might call the technologically-enhanced uncanny. It shows forests that the Tigers planted with the aim of building a truly independent, sustainable society, whose trees conceal ancient historical sites that are now in the custody of archaeologists appointed by the Sri Lankan government. Many Tamils regard this as a form of ecological and cultural occupation which tries to dilute their emotional and historical ties to the area. These concerns are articulated on the LED screens opposite.

Image courtesy of Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.

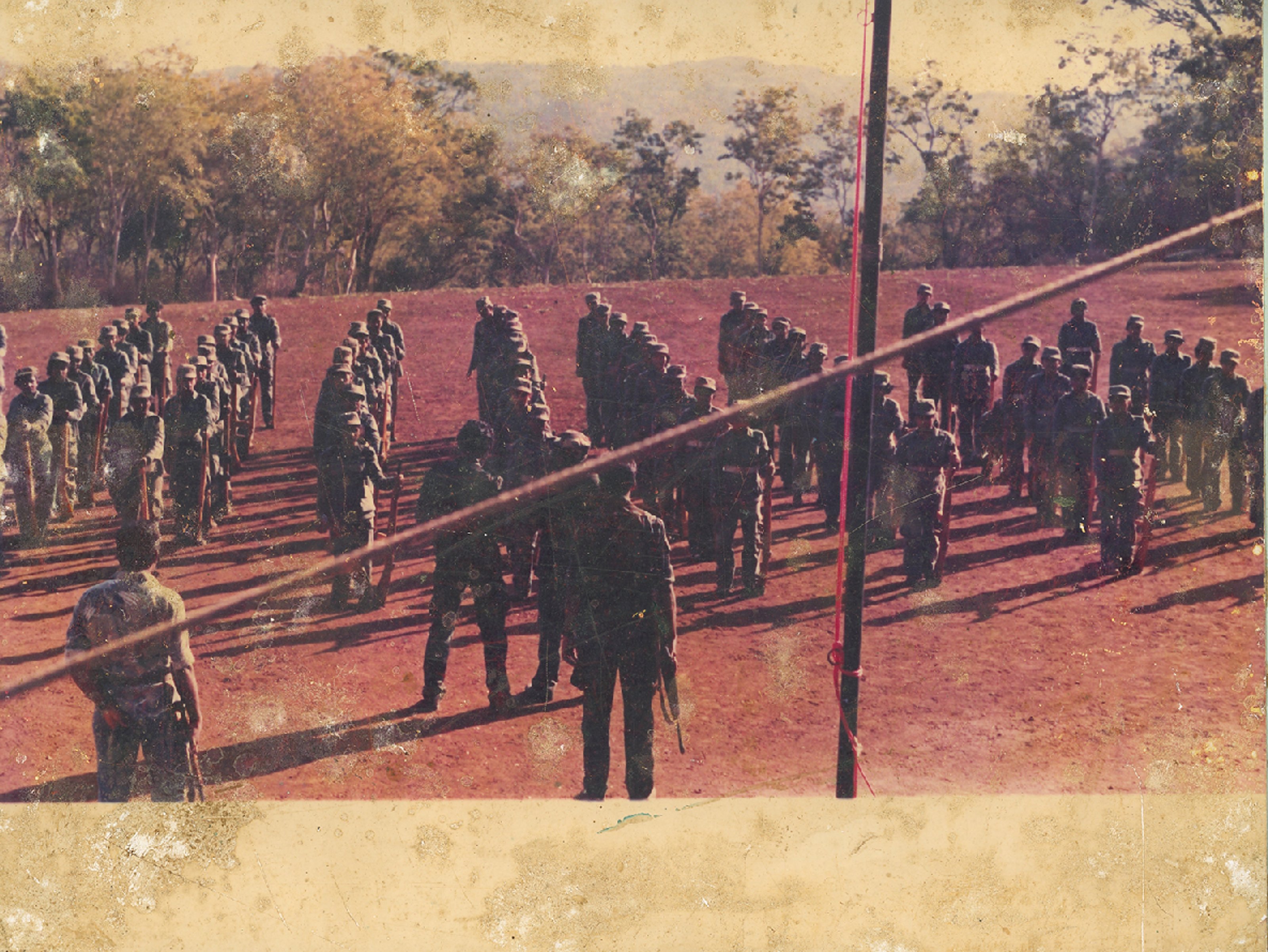

Here we see a range of different images from Sri Lanka, from uniformed Tamil Tiger militants taking part in combat operations and live-fire training, footage of fragments of everyday life in post-civil war Sri Lanka (driving through a city in a car, people dancing, interviews with the younger generation of Tamils), and images of the country’s startling natural beauty, including trees, ants, plants, and soil with a narrator describing how these ancient trees are where the soul goes after the body dies.

These images are juxtaposed with unexpected footage. Some include archival material from former American-football-player OJ Simpson during his infamous televised 1994 low-speed police chase through Los Angeles and his murder trial a year later. There is also what at first seems to be a straightforward, direct-to-camera interview with Kim Kardashian, whose father was one of Simpson’s closest confidants. At first glance, these parts jarringly contrast with much of the rest of the film, which features interviews with charismatic Tamil revolutionary Vasuky Vakay Jayapalan.

Image courtesy of KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin.

Jayapalan explains that, during and after British colonial rule, the Tamil people became a minority in their own indigenous homeland. In response, Tamil separatists wanted to create a decentralised state. At another point, she says that the ideal Tamil revolutionary should be able to commit to lots of different forms of activity, including making art, taking part in politics, and fighting in the military, creating a new, rounded form of human being. Jayapalan says that the centralisation of the internet is a way of controlling reality itself, and that the kind of genuinely free markets that would be created in a Tamil national homeland would ensure the common ownership of the means of production.

Image courtesy of KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin.

Image courtesy of Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.

Kardashian, meanwhile, describes how the internet and social media have “rewired” our brains and how the stories of oppressed groups – Tamils, Armenians, Palestinians – aren’t necessarily loud enough to be heard through the crowd of other narratives to gain emotional purchase. In the exhibition text, it is revealed that Kulendran Thomas has not, in fact, interviewed Kardashian at all, but has created a deep-fake, thus using technology to further warp reality even if, in this case, it is to use celebrity in order to draw attention to narratives that remain intentionally hidden to this day.

The question of who gets to tell their story and how is echoed not just in what Jayapalan and Kardashian say, but their public personas. Kardashian is a globally recognised celebrity. Her everyday life, including the most minute and intimate details of her habits and personal life, is very well documented. Even a basic search for Jayalapan, who was defined as a “terrorist” by the Sri Lankan government, however, brings up almost nothing.

Image courtesy of Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.

The film reflects on the problem of narrative by actively contributing to it. The result is that the viewer is forced to decide for themselves what is real and what is not, even if they are unable to fully settle on what that is. This expresses further points of fragmentation: of the simplistic idea that there is a single, stable experience of imperialism or colonialism, as if all oppressed peoples’ experiences were the same regardless of who they are and who the ruling power is or was; the confusion created by guerrilla warfare tactics such as those of the Tamil Tigers themselves; and the way knowledge is produced and disseminated in the age of global interconnectedness.

Radical social change means radical honesty, so part of thinking in these terms and deciding on what counts as real for ourselves means not discounting how the Tamil Tigers were known for the fanaticism of their fighters, their authoritarian rule in the areas they held, and their use of child soldiers and suicide bombers. Though these profound and troubling moral problems are not directly mentioned in Thomas’s work, it does not mean he ignores them. They rather appear as visual propositions about how art can be used to give glorious romantic lustre to political violence, flirting with some of the implied emotional energy of propaganda without being reduced to it. This is certainly disquieting, but not necessarily more so than what artificial intelligence or algorithms can do to our sense of reality.

Image courtesy of Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.

Thomas intimates the next step without saying anything openly. His use of archival material from the Tamil Revolution is just one example of an important problem: the relationship between what we can learn from liberation movements of the past and the revolutionary potential of new technologies. If they are going to be used for emancipatory purposes, they need to be used by oppressed groups to tell stories about themselves. Thomas’s work exposes some of these technologies’ inner contradictions, which become fully visible when we are able to see how the narratives told by oppressors overlap with counternarratives of liberation. The form in which these stories are told, and the techniques used to tell them, say as much about those who are doing the telling as those they are telling us about.

The Finesse implies that political censorship and certain kinds of historical revisionism contain early versions of the impulses now expressed in the use of deep fakes - which are being used by sinister forces across the globe. This shows us how there are few absolutes to grasp, and few guarantees in the present or the future. This leaves it up to the viewer to decide for themselves what is real and what is fake in Thomas’s films. If there is a clear emancipatory gesture, it’s the possibility that this process of thinking can extend the viewer’s understanding of how some digital sources manipulate them to the whole fuzzy, chaotic digital image-world in which we now live. Though there is another: by telling the story of Sri Lanka, the Tamil people, and their diaspora, Thomas asks vital questions about how digital technology transforms cultural memory. This turns to the classic question of how we tell ourselves stories about ourselves, handing them down from generation to generation, under radically new conditions.