NFTs are over - but Digital Art is all around us. With institutions such as New York’s MoMA1 and ICA Miami2 owning and selling tokens, what is certain, is that Digital Art is here to stay - but institutions are still struggling with how to display its new forms. One solution that has been used by artists for decades but which has only recently made its way into institutional exhibitions such as the contribution of Moana Oceanic Arts Collective FAFSWAG at Documenta 153 is Augmented Reality (AR).

AR is a real-time, real-space application that uses handheld devices to implement a digital spatial layer over physical reality. It inserts digital objects using the camera function that responds to our GPS coordinates as we walk through space. Most people have interacted with AR already through popular games, such as the 2017 fad of Pokémon Go – or the earlier global digital capture-the-flag game called Ingress.

While these games went through phases of activity and downturns, their technology is a Borges-esque real-world map that adds layers of complexity to our own. So far, it has been explored mainly by gaming communities, as is the case for most cutting-edge technology in the development phases. However, its applications are far wider than just games. Digital pioneers in the art world believe AR can serve to visualize underrepresented narratives, reveal hidden truths, and combat censorship in politically meaningful gestures of resistance.

Between 2020 and 2022, digital art experienced a Cambrian explosion fueled by the pandemic conditions in which we found ourselves. In these early days of experimentation, it was practitioners such as Daniel Birnbaum who set the stage for AR by opening the possibility of having a digital KAWS work in private residences with the virtual platform Acute Art.4 This platform offers art enthusiasts the chance to hang digital art in their own homes for free, rethinking how art can be arranged in augmented spaces.

Birnbaum got involved with this platform in 2019, just as it became a lockdown respite for those thirsty for art—but artists had been developing these methods long before. For a long time, AR was not accepted as a real expression of art by gatekeepers of the artworld.5 But now a few initiatives are emerging that have the potential to bridge the gap between the traditional art world and creative digital pioneers.

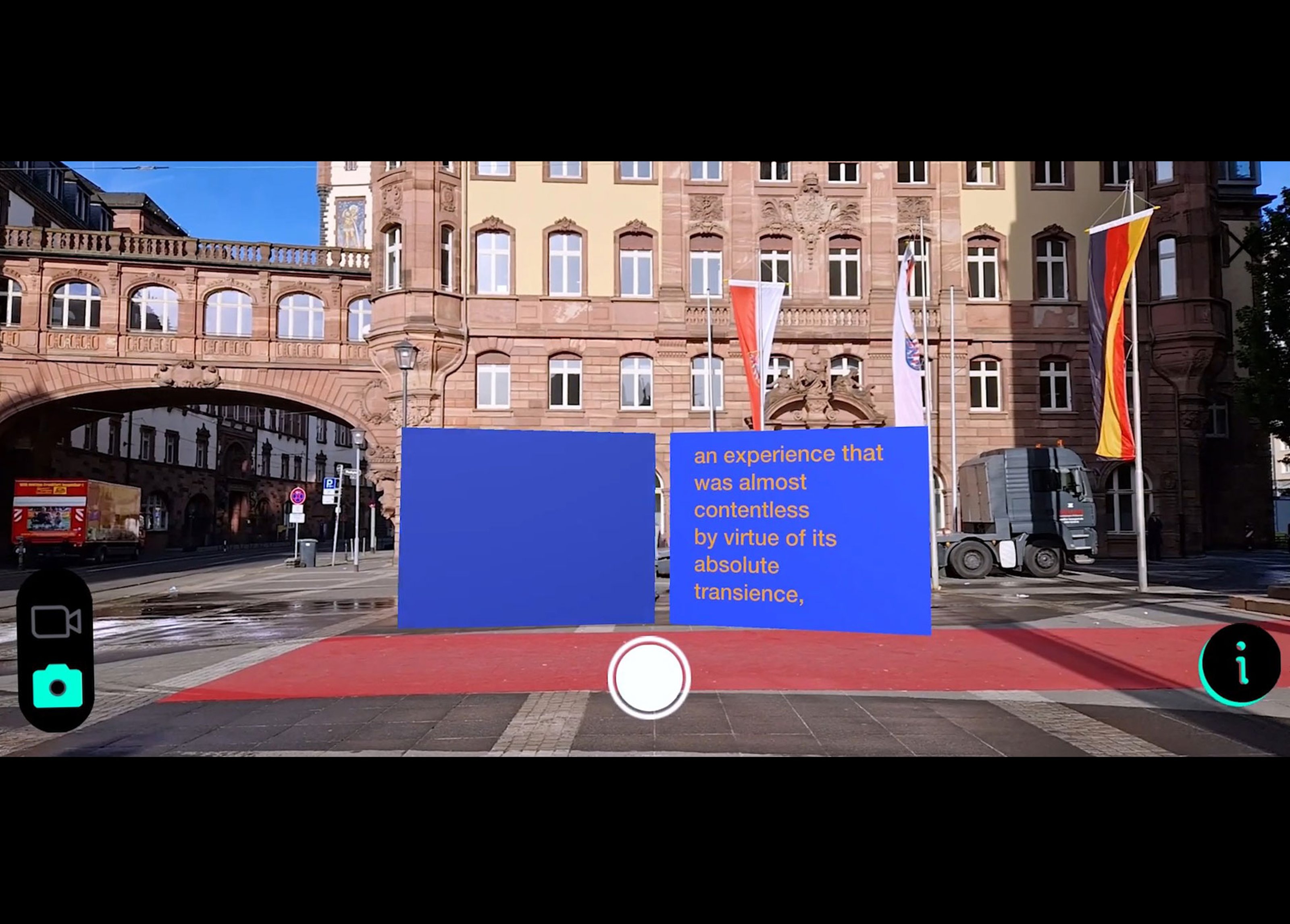

One of these platforms is WAVA, a virtual exhibition platform developed by Ben Livne-Weitzman, David Bachmann, Florian Adolph, and Grit Medea in Frankfurt-am-Main. This project was created by developers and artists from the perspective of a curator, inviting artists to participate in site-specific exhibitions with digitally-native works. Rather than soliciting artworks that can be placed anywhere, WAVA proposes that exhibitions remain site-specific and viewers move to the location of artworks, locating them through the app.

On the occasion of the 175th anniversary of the first attempt at a Democratic Parliament in Germany, the city of Frankfurt-am-Main invited WAVA to create an exhibition in public space around themes of democracy. In response, Livne-Weitzman invited a combination of artists working in digital art and physical art who connect well with this theme. Augmented Reality serves as the stage where artworks spark discussion on themes of democracy, censorship, and today’s most urgent political landscapes.

The structure of AR recognizes space as multitudinous, existing in overlapping layers of realities, similar to the structure of contemporary urban environments. While our perceived reality on the street is constructed over centuries by the powers that rule over urban and public spaces, AR can illuminate lesser-known narratives to evade censorship or open access to subcultures. Undercurrents and critiques of authority, the unsayable and the unseeable, are themes present in the works of Flaka Haliti, Morehshin Allahyari, and Tony Cokes. Allahyari’s Zoba’ah: The Whirlwind (2022) conjures a jinn from Persian mythology — the spirit nods to Frankfurt’s large Iranian community while asking visitors to pledge an action to make the world a better place before conjuring the being. Tony Cokes’s pieces SM BNGRZ 01.04 (2021) and SM BNGRZ 02.01 (2021) continue his work around the history of subcultures and dance music and the political momentum of POC and queer communities in developing underground resistance through togetherness. By bringing these works out into the public, the screens highlight the absence of fluidity inherent to the rigid control of institutional spaces.

Other works, such as Flaka Haliti’s Whose Bones? (2022-ongoing) and Les Trucs’ Bunte Stoffe - Eine Hymne (2023), directly use symbols of German national identity, including birds and flags, to revise national symbolism into critical perspectives. Early digital art pioneer Tamiko Thiel and /p created an immersive augmented installation that rains coins and constitutions from the sky. This work directly speaks of the consequences of this first parliament and its downfall brought about by Prussian and Austrian forces in the 19th century. The implication might be that in a country like Germany, attempts at Democracy must be duly examined next to their failures and the delicate balance of political authority and finance.

Ahmet Öğüt / Monuments of the Disclosed, Aaron Swartz, 2022

Ahmet Öğüt / Monuments of the Disclosed, Kimberly Young-McLear, 2022

Ahmet Öğüt / Monuments of the Disclosed, Kimberly Young-McLear, 2022

Ahmet Öğüt / Monuments of the Disclosed, Li Wenliang, 2022

Ahmet Öğüt / Monuments of the Disclosed, Marlene Garcia-Esperat, 2022

One of the exhibiting artists is Collecteurs community member Ahmet Öğüt with his recent series of digital artworks Monuments of the Disclosed (2022). This series comprises nine digitally-native monuments to truth-tellers and whistleblowers who would otherwise never see a monument dedicated to their efforts. Five of these tributes are included in DEMO- in site-specific locations tied to issues of democracy and censorship. The monument to Aaron Schwartz is positioned on an easy-to-miss GPS coordinate in the center of Frankfurt that speaks to our contemporary condition of constant surveillance and geographical mapping in relation to Schwartz’s activism for open access internet resources. Another monument is to Doctor Li Wenliang who warned about Covid-19 in December 2019 and was subsequently accused of spreading false rumors by the Wuhan police. Placed in front of the Chinese embassy, this monument shows that AR can supersede boundaries of censorship and highlight untold narratives.

Not everything about AR is perfect – it contains many hiccups that are inevitable in the early days of any technology. These include access to devices and equipment to experience it optimally— while an institution can strive for equal access for all viewers, AR requires a device compatible with the software of the application, which is not always accessible to participants. While handheld cellular devices work fine, larger screens, such as tablets, work better for viewing, and a good pair of headphones that connect to that device would optimise the experience. Such is the case with the work of Tony Cokes, whose explorations into underground genres of house music are known to produce bodily base vibrations, need to be content in this case with tiny cellular phone loudspeakers. AR doesn’t presume to reproduce festival-quality sound, but its flaws are outweighed by its ability to place his sonic work in public at all.

The physicality of exhibitions in a world that is rapidly embracing digitally native works is an issue to contend with for traditional institutions as well as the art market. Some years ago, Collecteurs spoke with Alain Servais about the conservative aesthetics of marketing video-art and Digital Art; DABs seem to be suffering similar fates. Exhibitions showing off the NFTs from pandemic hype have attempted to show these works by flashing them on flat screens surrounded by square frames, which only makes the antiquatedness and awkwardness of digital worlds in the art field more glaringly obvious. We need solutions to integrate these two worlds or to create new and parallel institutions that can adequately mediate these works to a broader public.

Digitally native artworks need new types of markets as well as institutions and exhibition models. While institutions attempt to attract new audiences, AR might also hold the key to the participation of younger generations in contemporary art. At Collecteurs, we see digital possibilities as an important vehicle for transparency and accessibility in the art world, including our series of digital exhibitions accessible to everyone with a device and access to the internet 24 hours a day. Handheld devices are now more than ever part of our social lives as a method of identity and community-building.

At the end of the day, an app is the product of dedicated teams whose labor and construction keeps up with updates and system requirements. Similar to the work of institutions, they must keep up with standards and expectations of cultural systems. Developers are currently building the blueprints that will become institutions of the future to host the collections that we already own but don’t yet know how to exhibit.