In 1984, Michel Foucault passed away from what was recorded in hospital as a ‘rare brain infection.’ In his obituary in Le Monde, there was no mention that this disease was in fact a symptom of an advanced HIV infection. The philosopher of Biopolitics, Madness and Civilisation, Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality suffered at the end of his life from the very regimes of state manipulation and bio-political censorship to which he dedicated his career. It was through the persistence of his partner Daniel Defert, who went on to found one of the largest HIV/AIDS foundations in France still operating to this day, that this information was revealed to the public.¹ In the late 80s and early 90s the United States government went so far as to defund art spaces that tackled issues of HIV/AIDS,² and in the case of David Wojnarowicz who experienced that form of censorship in life, his work was censored again in 2010 by the Smithsonian and National Portrait Gallery.³

Paul Preciado opened his ‘Cartografías Queer’ by positioning this censored death via Biopolitics at the fulcrum of a new theory of queer cartography.⁴ It is precisely Foucault’s definition of space as heterotopia that describes the spatiality in the works of Félix González-Torres. Heterotopias are defined by difference – they are spaces with more layers of meaning than immediately meet the eye. It is a queer cartography in which layers exist upon layers – in which infinite private multitudes revolve around singular public events, and in which censorship and the state create one narrative which is undermined by networks of many others. It is a human effort to overcome the narrative power of the statistical count of bodies through the lived experience of multitudes of powerless voices. It is in this way that González-Torres’ work forms a queer cartographic archive that functions not as a collection of material sources but whose form is dispersal.

Heterotopias are created through González-Torres’ admixture of public and private events via archival traces. His own life is the base for a narrative whose form is one of loss and a constant weathering away but which finds an afterlife in its dispersal. The loss of his partner Ross Laycock in 1991 to AIDS-related illness, and his own subsequent struggle with its effects, mixes into the fabric of the violence of American society and the biopolitics waged on the LGBTQ community during the decades of the 80s and 90s. González-Torres lived through a time when a campaign of invisibility left those who suffered from AIDS only with the possibility of leaving rogue traces. This is how he spread his artwork through the institution. Through generosity, he spread to homes around the globe and across all incomes, weaving a connected human archive. He claimed in an interview that he imagined his works to spread ‘like a virus that belongs to the institution’ and, in this way, replicate himself indefinitely.⁵ His work takes the form of a conceptual archive that flows with individuals that act as carriers and infect the institution and the private home.

Félix (2020) is a self-reflexive exhibition that exposes traces of his life, the memories of his family and the death of his partner Ross Laycock – using the archival format to mirror his artistic process of generosity by offering information and documents in digital form. This exhibition is necessary because his life and work are inextricable from each other, and the traces he left behind perform an extension of each project. González-Torres’ work consistently employs combinations of private moments with public news stories and private events to form timelines of experience and challenge mainstream narratives. If González-Torres uses his own personal archive as source material for his works, this exhibition proposes a deeper understanding of his biography as a method of approaching his original intention. If Brecht and Roland Barthes were important theoretical figures in his work⁶, they were overshadowed by the influence of his partner Ross – and this shows his consistent application of theory and the public sphere as an important but distant influence compared to his personal contacts. The archive in González-Torres’ work is a body, and one that disperses with the audience. Each wrapped candy dissolves in a sweet sugary sensation on the wet tongues of the audience, like a rogue Eucharist that only reveals itself to be a body once it has already been ingested. Through these works, González-Torres reaches out to touch the audience physically and materially, even being ingested to continue his life through the vitality of others.

“Untitled” (Welcome Back Heroes), 1991. Bazooka Bubble Gum, endless supply. Overall dimensions vary with installation. Ideal weight: 200 kg (440 lb.) © Estate of Felix Gonzalez-Torres / Reproduction facilitated by The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

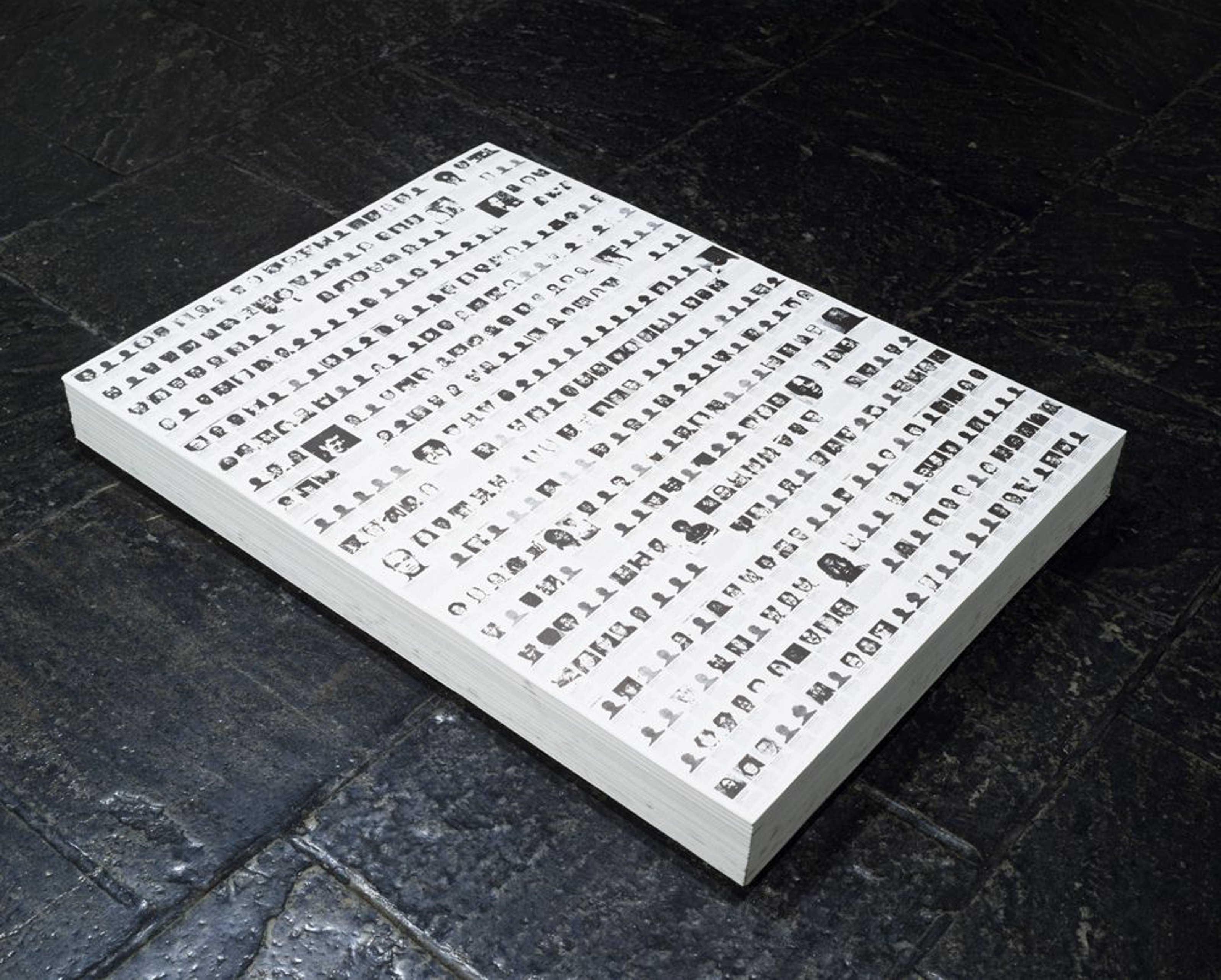

And yet, it is not only the population struggling with AIDS who suffered censorship, and González-Torres uses the absurdity of his country’s own inability to end suffering. In Untitled (Death By Gun) (1990), he uses the photographic archive to highlight the severity of the gun crisis in the United States. A group of 460 people are connected by their deaths occurring by gunshot from the 1st to 7th of May 1989. Their black and white photographs with the sterile press text describing their deaths are archived on a stack of printed papers 9 inches high. Thirty years later, nothing has changed, and his work remains active in denouncing the senseless suffering caused by the government’s lack of will towards protecting its own people. The paper stack is a form that González-Torres would use several times. It adheres to his philosophy of art’s accessibility by offering the visitor to take a copy with them and formally likens itself to the physical archive. By acquiring one of these papers, the audience not only accepts González-Torres’ gift, but activates the artwork by spreading it throughout the world as a carrier.

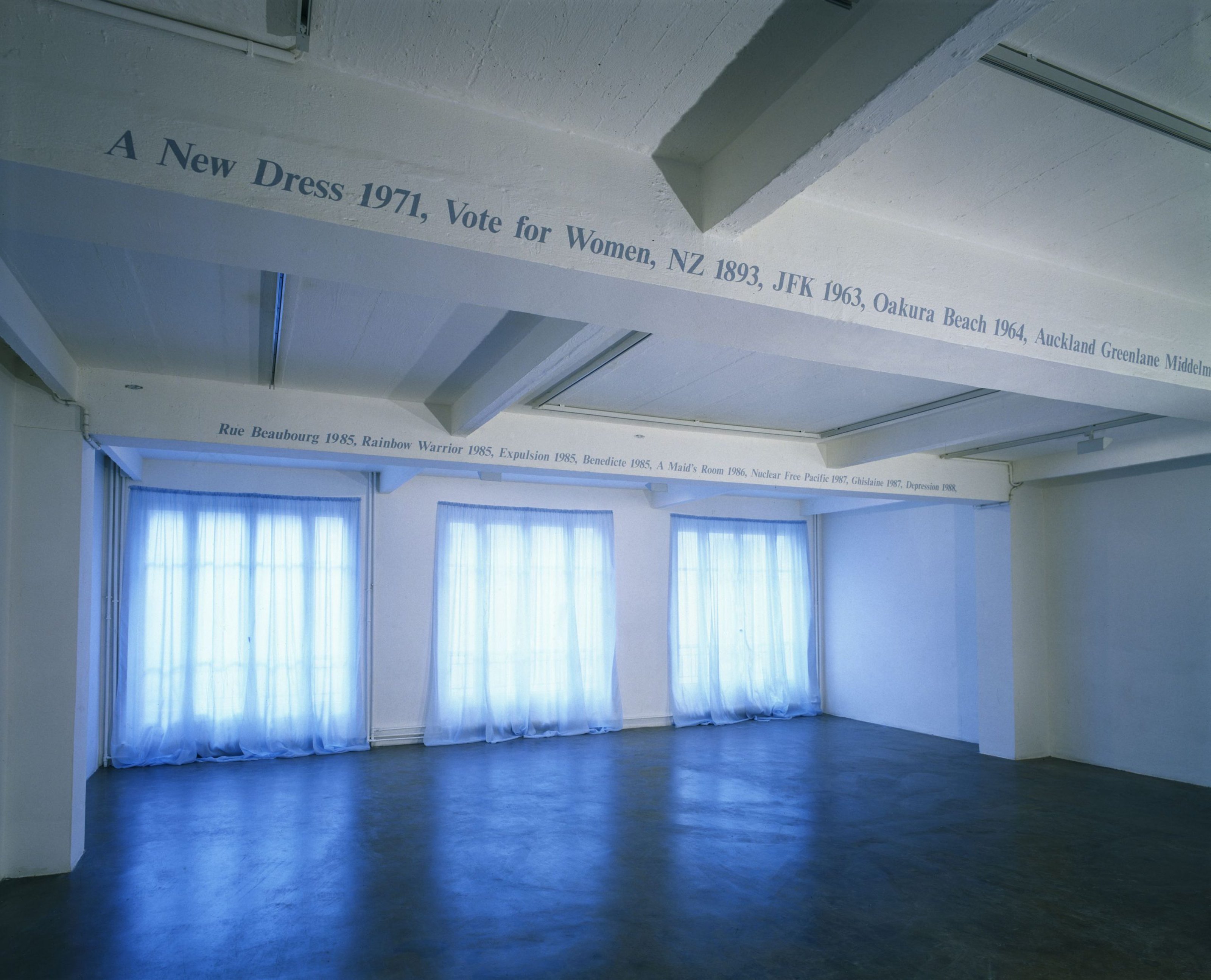

Another participatory archival piece occurs in the construction of his Dateline series commenced in 1987. These works assemble various dates and include largescale global events, public figures, and cultural artefacts that relate to that moment in time.⁷ The audience is encouraged to imagine where they were at that point in their lives. Untitled (Portrait of Jennifer Flay) (1992) uses one specific example of a person to fill in private memories; he calls these portraits as they record a moment of an individual’s life and the context in which they were lived.

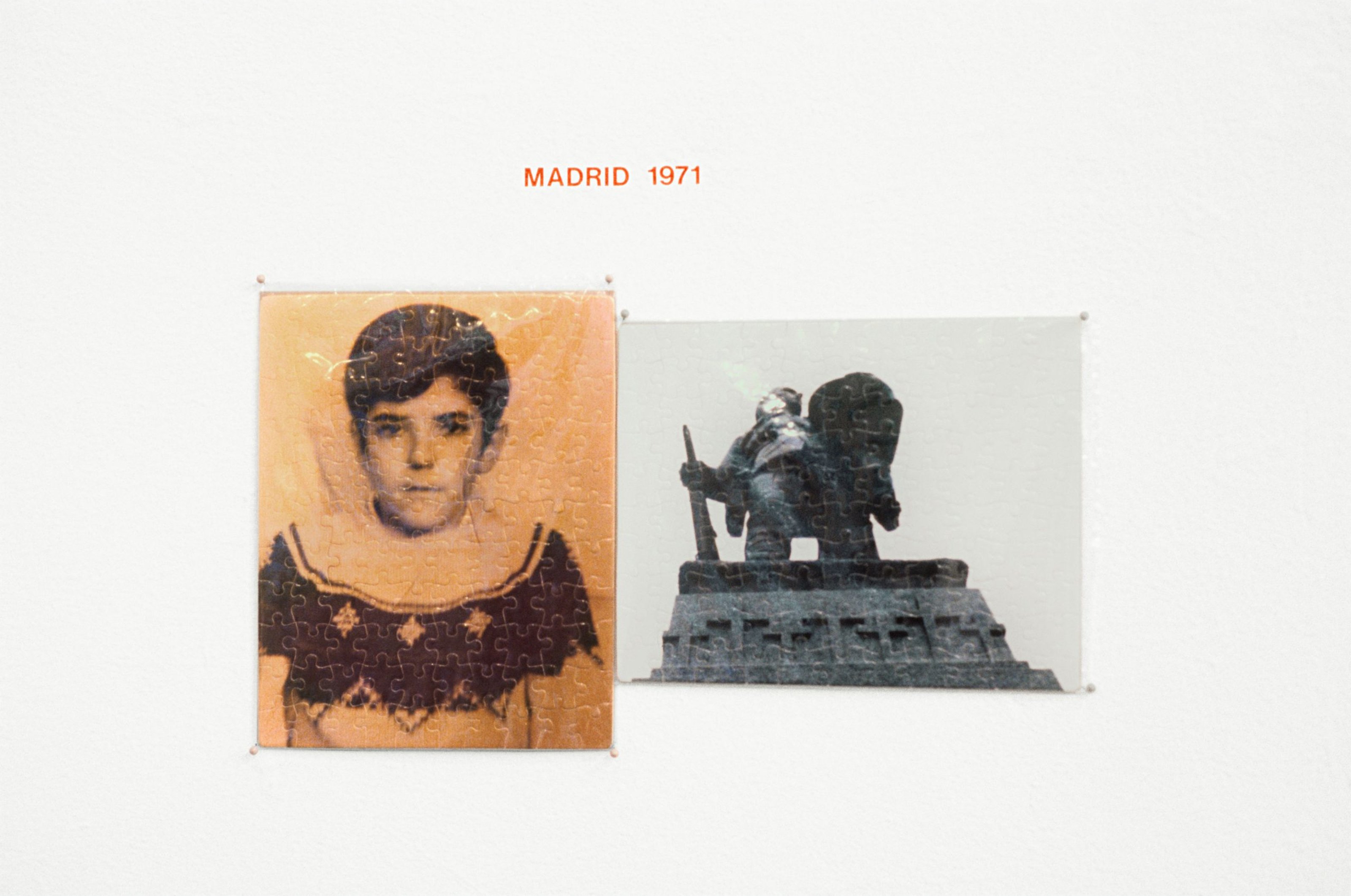

He often used examples from his own life, such as in Untitled (Madrid 1971) (1988) which employs his own childhood portrait next to a static monument seen from below in which the only discernible trait is the large rifle held in its right hand – an issue he would delve into both in Untitled (Death by Gun) (1990) and Untitled (NRA) (1990). In 1971, he was sent to live in Madrid together with his sister Gloria M González-Torres where they spent the year living under the military dictatorship of Francisco Franco. Both images are printed on puzzle pieces – another format that indicates the fragility and complex network that holds history together. Its pieces rely on one another to create a complete image.

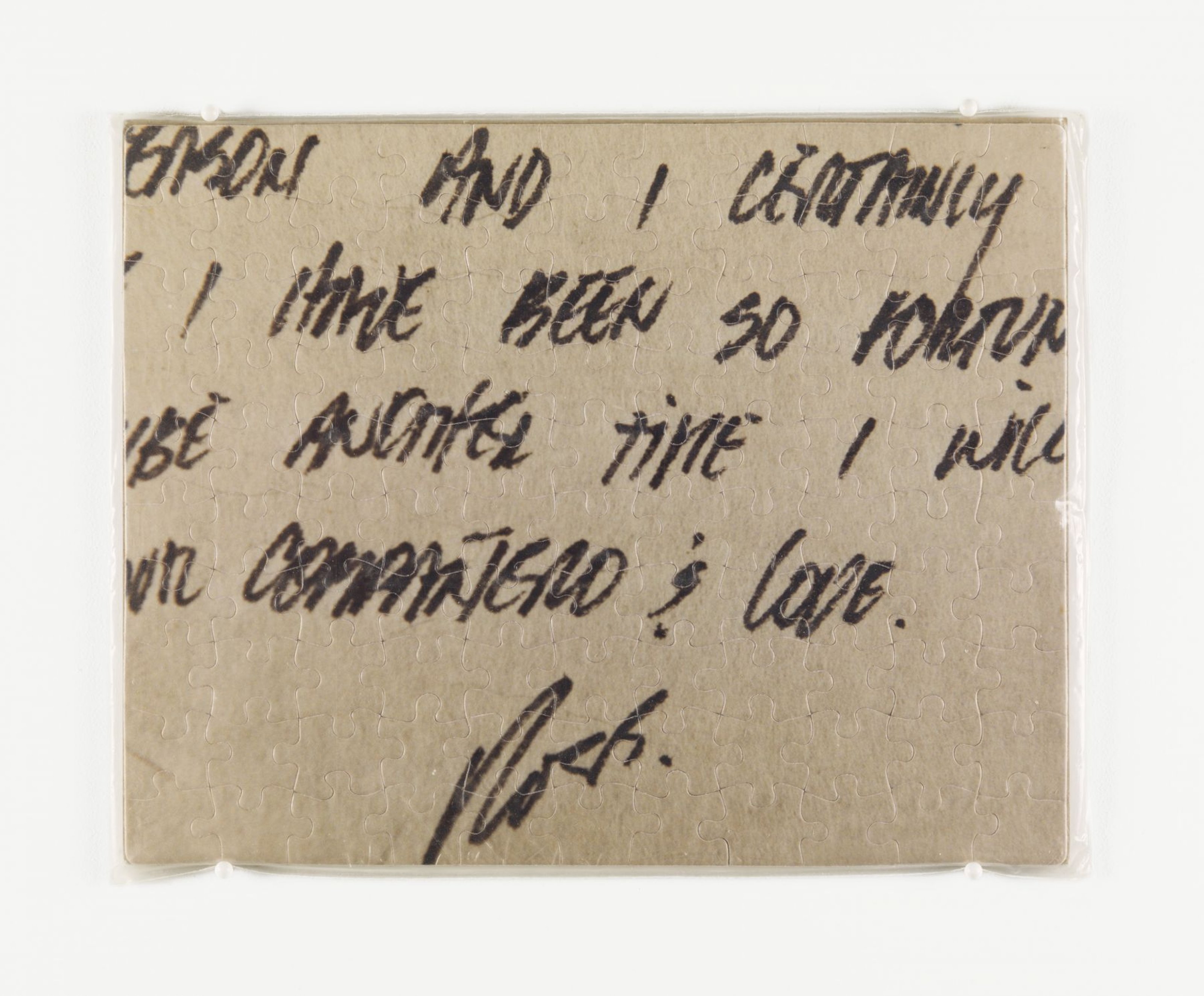

In 1991, after the passing of Ross Laycock, his last trace became a puzzle piece. Untitled (Last Letter) (1991) is a work printed on a puzzle base that frames Ross’ last written words and his handwritten signature on an otherwise cropped-out paper. The signature hovers under the last word – love – the work elicits emotion with the most basic words and the indication of their connection to an individual. The work challenges the narrative of an AIDS crisis as a series of statistics by revealing what each single death truly means, the honesty of the handwriting, the love once shared, the lives lived among its horrors, the scale of a tragedy is recorded in a single hand-written note. This primary document, the physical paper on which he last wrote, begins to replicate and infiltrate the institution.

After the passing of Ross Laycock, González-Torres’ own body began its swift decline. The biopolitics of the archive present themselves in the work called Untitled (Bloodwork) (1993) in which a series of gridded papers show a steep decline of T-cells. The simple hand-made line employs the aesthetics of minimalism but its title reveals to have not only a formalist but a strong social significance in tracing the body’s steady decomposition. These works exploit the language of minimalism in order to reveal the genre’s irrelevance. Form becomes a tool to enter the institution, and its deeper social meaning is the underhanded element that rears its head from behind the walls of censorship.

Félix González-Torres was an artist who challenged the materialist tenets of his time.⁸ Over those decades when minimalism and figurative painting dominated the art world, González-Torres rejected them. He described his discomfort at the ways in which American society expected a gay man with AIDS to work with highly ‘erotic and pornographic’ work,⁹ rejecting sensationalism and instead infiltrating space with delicate subtlety. When it comes to his archive, he contributed to it all the time. Details like handwritten notes sent to his family, photographs taken of the sky, and series of letters sent back home constitute part of his artistic process. His life was a great work of art in which he lived by the tenets of generosity and seeking out the truth. The archive is a collection of the paper trail which the body sheds and stands in parallel with his productive work. As described by Laura Bravo: ‘through the process of losing his life, Félix González-Torres gains immortality.’¹⁰

Àngels Miralda (1990) is a curator and writer currently participating in De Appel’s Curatorial Programme. Her interests are anchored around the concepts of landscape and identity woven by artist’s works and personal stories. Recently she has collaborated with contemporary art centers such as the Tallinn Art Hall (Estonia), the MGLC – International Centre for Graphic Arts (Slovenia), the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art (Riga) and the GMK municipal gallery in Zagreb. She is a regular contributing critic for Artforum and a long-time collaborator of Collecteurs.

Footnotes: