The centerpiece of Emily Jacir’s Notes for a Cannon (2016), created for the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in Dublin, is a site-specific sound work at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham Clock Tower. Meanwhile, inside IMMA an exploded array of images, documents, sculptures, video, and objects results in an interconnected constellation of historical and social struggles in two distinct geographies for national liberation against British occupations. The anticolonial struggle in Ireland and Palestine share a long history of solidarity and lived experiences that testify to the globalized brutality of the British army in its quest for military domination.

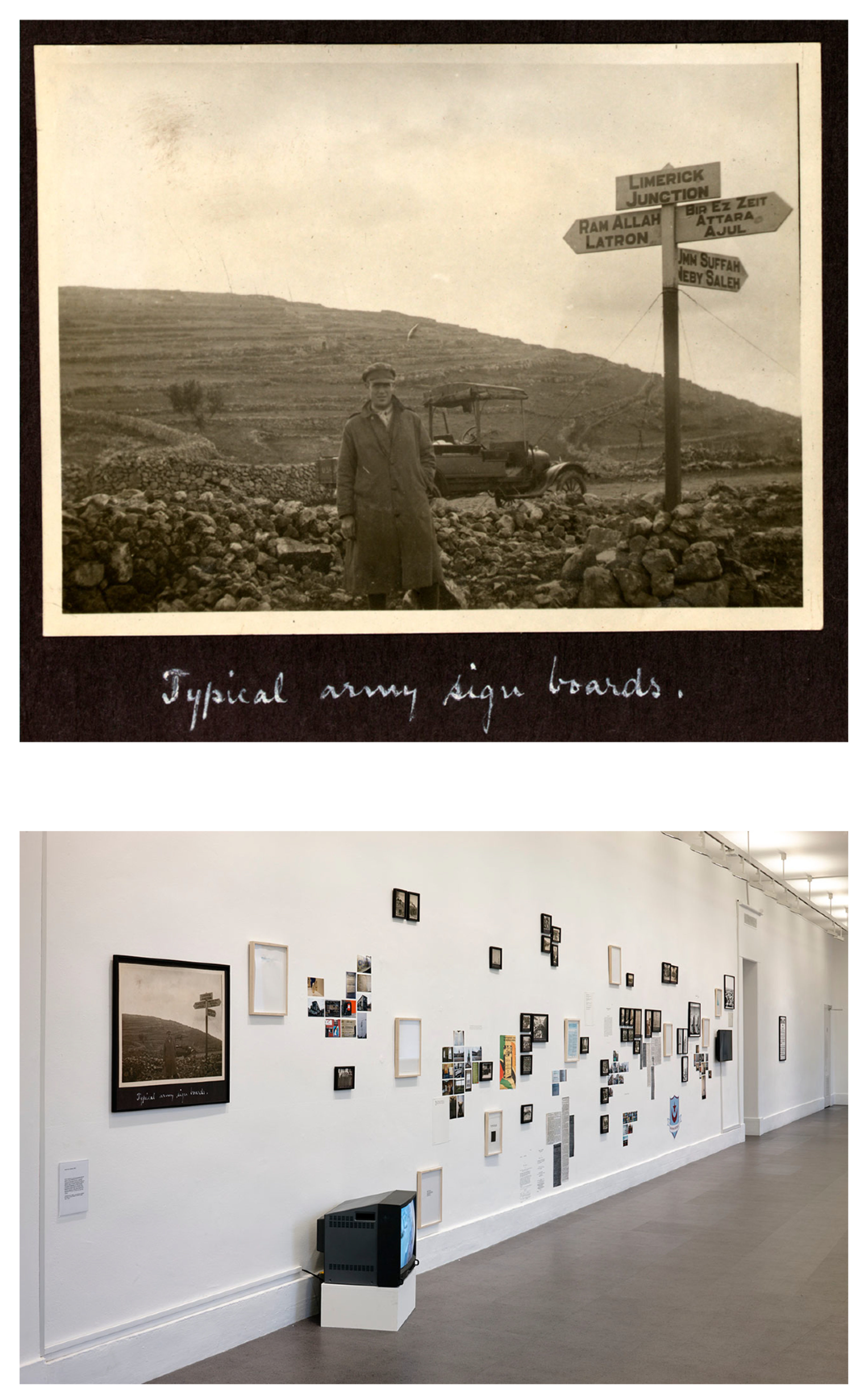

Emily Jacir / Notes for a Cannon, 2016, (Palestine cluster), installation view, Irish Museum of Modern Art Dublin, 2016, photography by Denis Mortell.

Images, documents, and sketches appear as a shattered mosaic that delves into historic aporias of memory through its fragmentary positioning on the museum wall. Arranged like an archipelago, it connotes the land-locked military separations of the West Bank and the isolation of Gaza into the world’s largest open-air prison. Both the Palestinian and Irish catastrophes are a product of the planned necropolitics against their people that result in dispersed global communities that continue to fight for their cultural memory and resistance from around the world.

Emily Jacir / Notes for a Cannon, 2016, installation view, Irish Museum of Modern Art Dublin, 2016, photography by Denis Mortell.

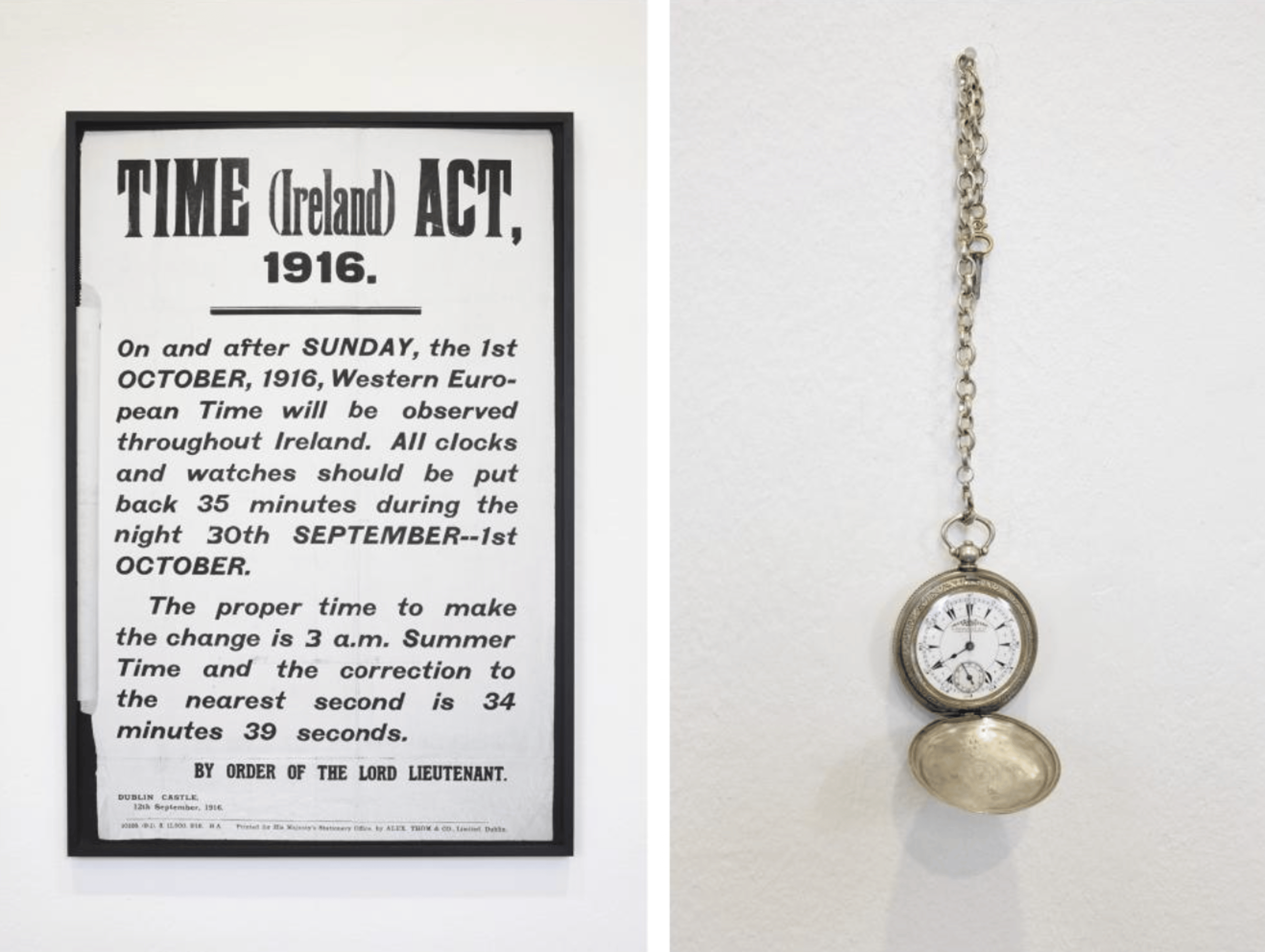

A large photo on the wall reads “Time (Ireland) Act.” This ordinance by the British authorities assimilated Ireland into “Western European Time” and eliminated Dublin Mean Time. The Irish people were instructed to turn the clocks back by 35 minutes on the night between 30 September and 1 October 1916. The newspaper clippings that form part of Jacir’s project describe the violence of this act, serving as a nonconsensual erasure of an independent identity and infringement of the people's right to self-determination. The change created daily inconveniences for agricultural and factory workers who from then on, no longer worked by the hours of the sun and instead had to rise 35 minutes earlier in order to conform to English standardization. This work serves as an example of the many experiences of what Foucault would term the “micro-violence of discipline”1 by the ruling colonial class against its subjects.

Emily Jacir / Notes for a Cannon, 2016, (‘Time Act’), installation view, Irish Museum of Modern Art Dublin, 2016, photography by Denis Mortell.

The site-specific sound piece installed in the clocktower of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham expanded into the streets of Dublin, where the colonial standardization of time finds a parallel in Palestine’s history. In 1922, the British officials in Jerusalem demolished the Jaffa clock tower that told time in both “European style” standardized time and “Ottoman style” - time in which high noon shifted with each day according to the temporality of the sun. The clocktower was a testament to how two different perceptions of time can live side-by-side in harmony. The demolition of the tower during the British occupation was a negation of this possibility and enforced the supremacy of British time, tied to Greenwich, standardized across all colonial territories. Jacir overlaid these three modes of timekeeping during her exhibition at IMMA. For the duration of the exhibition, a bell struck from a tower 12 times at Dublin Mean Time - signaling noon 35 minutes out of sync with what is now Irish time (GMT). At noon Greenwich Mean Time, the sound of a single cannon shot rang out from the tower. And finally, at “Ottoman style” noon, the call to prayer from the tower echoed throughout the area, gradually shifting in relation to the sun as well as in proximity to both DMT and GMT noons.2

Emily Jacir / Notes for a Cannon, 2016, (‘Time Act’), installation view, Irish Museum of Modern Art Dublin, 2016, photography by Denis Mortell.

In a long-form article by David Lloyd titled “Redemptive Constellations” Jacir’s work is contextualized to the writings of historians Rashid Khalidi and Richard Cahill as they trace the individual military officers and colonial tactics that operated first in Ireland and later in Palestine.3 The use of propagandistic tools such as the abuse of words such as “terrorism” or “criminal” can be traced throughout former territories under British rule.4 Winston Churchill who famously justified ethnic cleansing and genocide had compiled a white gendarmerie called the Black and Tans that had been responsible for grave atrocities in the Anglo-Irish war. This regiment was sent to Palestine after their failure in Ireland.

Lloyd’s text quotes historian Richard Cahill’s article “Going Berserk: Black & Tans in Palestine”

Emily Jacir / Notes for a Cannon, 2016, (top: Limerick Junction), installation view, Irish Museum of Modern Art Dublin, 2016, photography by Denis Mortell.

This shared history of British colonial rule between two former colonies illustrates the global application of brutal methods on behalf of an empire that has left the earth scarred and divided from India and Pakistan, to Ireland, to Palestine, to the Native reservations in the United States and Canada. The churning of history condemns the present to face the unfinished consequences of these historical violences.

Emily Jacir / Notes for a Cannon, 2016, (Drogheda cluster), installation view, Irish Museum of Modern Art Dublin, 2016, photography by Denis Mortell.

In 2016-2017 Jacir organized pedagogical workshops at IMMA titled “To Be Determined (for Jean)”.6 The title is a nod to the work of decolonial writer and curator Jean Fisher who connected the struggles of Ireland, the indigenous people of North America, and Palestine as well as a legacy of art education. In tandem with the exhibition, Jacir invited Irish colleagues including Willie Doherty, Conor McGrady, Gerard Byrne, Shane Cullen, and David Lloyd - all of whom had existing ties to Palestine through decades-long collaborations with Emily. The workshops demonstrated the long histories and influences between these two places and served to add to the themes already present in the exhibition.

Jacir also formed a school for young artists at Firestation Artist’s Residency in Dublin, where various themes became the focus of historical research and analysis. One focus was the current situation of Palestinian prisoners and investigated parallels in South Africa and Ireland where prisoners played crucial roles in both struggles. Another mode discussed migration and citizenship laws that regulate settlement and movement. The historical archives shown through the exhibition were enacted and lived through conversations and activities that worked to actively build communities and strengthen existing ties that provide hope for a future of global solidarity.